By Amaresh Dubey & Shivakar Tiwari

Since the imposition of complete lockdown on March 25, which is the most potent weapon to fight Covid-19, economic activities came to a screeching halt. This resulted in an unprecedented situation for the entire community of workers. But, in the metro cities, brimming with a large army of migrants engaged in informal work, the situation is alarming because of the loss of livelihood and confinement of workers and their families in crammed spaces. Loss of livelihood has created a situation of food scarcity from the very beginning of the lockdown, and forced confinement has created a sense of unprecedented insecurity about fulfilling basic needs. As a result, hordes of them have been gathering at bus and train stations in several states like one at Anand Vihar bus and train terminal last month, and at Bandra station recently. There are several accounts of migrant workers proceeding on long and arduous treks and walks, or using any available means to reach home at faraway places. In frustration, they have even resorted to arson and other forms of violence as happened in Delhi’s shelter home.

The government and civil society have been stretched to the limit in trying to provide ration, cooked meals and water to the migrant labourers. Even this massive effort seems inadequate as apparent from all kinds of account of food shortages. This is because the sheer number of mouths to be fed runs into millions. We provide an estimate of the number of those who have lost almost all income, rendering them desperate for means to fulfil not only their basic needs but also of their dependents. For capturing the enormity of the problem, we consider urban areas of two adjoining districts of coastal Maharashtra-Mumbai (including suburban Mumbai) and Thane, which is among six megacities as the hotspot for the Covid-19 spread.

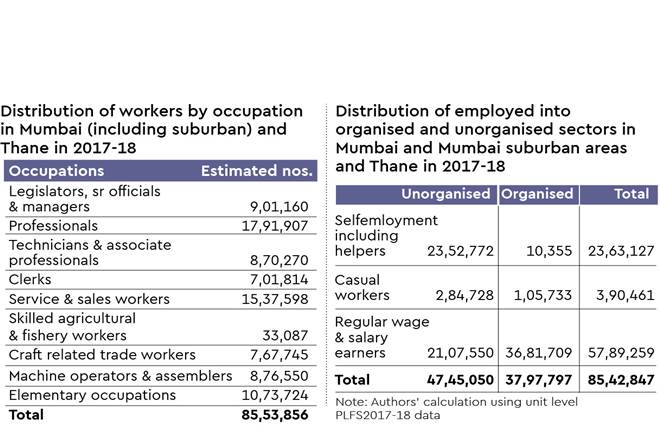

Estimated total urban population in 2017-18 in Mumbai and Thane together is over 24.2 million, with nearly two million migrants from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar alone. Distribution of workers by broad occupations in Mumbai and suburban areas and Thane is reported in the accompanying graphic. Out of over 8.5 million workers, close to 2.7 million are in white-collar and blue-collar jobs with stable income and decent living conditions. The graphic shows cross-classification of the workers in the unorganised and organised sector by the type of employment. Out of the total working, close to 5.8 million reported having regular wages and salaried employments, leaving about 2.75 million earning their livelihood from self-employment and casual work. Even among regular wage earners, 36%, or a little over 2.1 million, are employed in the unorganised sector. All this adds up to a whopping 4.8 million workers who are engaged in the unorganised sector. The unorganised sector provides various kinds of services where earnings of self-employed and casual workers and regular wage earners depend on daily turnover.

The lockdown notification decrees that wages and salaries are to be paid during this period. In the formal organised sector, salaries could be paid, and it is also possible for a proportion of regular salary and wage earners in the unorganised sector to get paid. Still, a large proportion is not likely to get paid as the employers paying capacity is determined by daily cash flow. For unorganised and self-employed workers in other occupations, e.g. trading and retail in the non-essential category, transport, restaurants, etc, it is unlikely that employers can pay wages to casual and employed workers. Casual labourers have to be off the road, hence, no possibility of getting daily wage work. Similar earning loss is there for the self-employed in other sectors. For example, transport services comprise of passenger autos and taxis, goods carriers-small tempos (like autos), medium-size tempos and trucks. While a proportion of goods carriers-tempos and trucks may be engaged ferrying essential supplies and services, passenger auto services are off the road. By a recent estimate, over 3,00,000 autos ply in sub-urban Mumbai and Thane in 2018-19. Similarly, there are over 1,10,000 taxis, including app-based and local taxi providers. The lockdown has rendered the earnings of over 4,00,000 drivers (it could be much more than the number of autos and taxis as sometimes these are driven by multiple drivers in shifts) to zero.

The massive loss in wages and other earnings among workers in the unorganised sector brings us to the issue of the mobility of these workers during the period of lockdown. It is a well-known fact that space in Mumbai is at a premium, even the workers categorised as lower middle class are found to be living in slum-like accommodations sharing basic sanitation facilities. The condition in the slums in a situation of complete lockdown could be worse than one could imagine.

According to one estimate, more than 5.2 million persons are living in slums in Mumbai alone, and their number is rising. It is estimated that Asia’s largest slum, Dharavi, alone could have as many as one million habitants in an area of barely two square kilometres making social distancing impossible. A household (typically of about 4-5 members) is forced to live in a small room, and in many instances, a number of single male migrants share a room. In normal circumstances, members stay in the room by turns as they work at different times. With the imposition of the lockdown, all members of the household are forced to be together simultaneously. There are already reports from the jails in the US and elsewhere that, convicts are not able to maintain social distancing. Consequently, the jails have become hotspots of Covid-19 infections.

With the total loss in income of a large proportion of self-employed and casual workers, they are living in a precarious situation. While immediate worry has been food, other problems are unhygienic condition, as they have to share toilets, fetch water from the same source, resulting in vulnerability to various ailments. It is known by now that fatalities due to Covid-19 are significantly higher among those with other short-term morbidities. Besides extremely limited scope for maintaining social distancing norms along with maintaining basic hygiene, migrants have limited social network to rely upon in times of crisis in the large cities. Unlike in several other countries, migrants in India have a very strong affinity with their families back home. Therefore, they have been living on the edge with a wish to return home. It is good to decongest the slums by arranging travel of migrants to their home in an orderly manner without losing time.