Climate adaptation, mitigation, and resilience require trillions of dollars of financing. Green finance has hence caught the attention of companies, investors, regulators, and policy makers. As climate change creates new industries, it creates the opportunity to reshape the economic landscape—such a reshaping can create significant new opportunities, incomes, and wealth. No wonder the world of finance is deeply invested in this trend.

Green finance has recently seen significant deliberations and action: it is the centre piece of policy initiatives, for example, with high-powered bodies like G20, central bankers, and securities market regulators. Many committees and policy bodies have worked hard to define what constitutes green and where such finance may be used.

Sovereigns across the world, including India, have issued green bonds. These bring together investors who want to park their monies for assets that invest in assets that engage in green or climate-friendly sectors. The issuance of green bonds by corporations and the creation of green financing entities (funds, non-banking finance companies, bank deposits, etc.) highlights how wide the ecosystem now is.

It is important to pause and reflect on the composition of green finance. As we know from investing and corporate finance 101, neither is all capital the same when it comes to risk-return characteristics, nor are all the projects and industries at the same level of maturity and capital need. What type of finance is required, when, and in what quantum varies significantly: a clear framework can help channel appropriate interventions from policy makers and financiers.

Detailing the framework

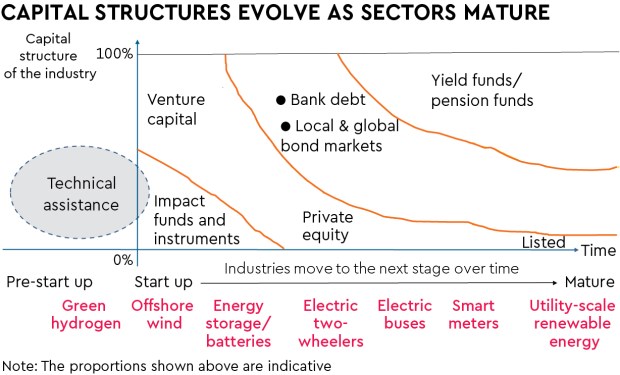

The accompanying graphic gives an overview of the landscape of green finance. The horizontal axis highlights how an industry matures over time while the vertical axis details the type of capital that is required at different levels of maturity. Combining these two, we can see where different providers of capital operate: as the risk-return-quantum of capital changes, players providing capital and the nature of capital changes. This has implications for policy design to attract and incentivise capital.

Understanding the maturity: Many industries in the climate ecosystem have emerged over the last couple of decades; the excitement is about newer industries taking shape. Led by innovation both in technology and policy, newer industries are becoming viable. As with any new sector, there is a pathway of maturity: think of the horizontal axis in the graphic as a timeline through which industries travel. Not all industries take the same amount of time, and some may jump stages quickly. We note names of some industries to indicate where they currently lie on the timeline in the case of India. Before an industry can see “start-ups”, there is a phase of regulatory and policy design which shapes the sector. Then over time, as the technology evolves and policy stabilises, a commercial market can emerge that allows providers of capital to earn an appropriate return on their investments. The process is neither linear nor smooth: note that we have not introduced the intra-industry competitive dynamics in this framework.

Understanding the capital providers: The vertical axis of the graphic indicates the proportion of different types of capital required for the level of maturity in the industry. The left side of the vertical line indicates the phase of market development which requires capital with policy expertise without seeking a specific return. For a young industry that emerges thereafter, the risk is assumed by venture capital funds looking to back the next set of technologies that could scale quickly. However, given the uncertainties, new and younger industries can also benefit from impact funds and instruments (like guarantees, first loss guarantees, impact/first-loss capital, etc.) Note that in such young sectors, debt providers like banks, etc, are missing simply because the projects are too risky for them. As the industry matures, the role of impact funds comes down, larger cheques come in from private equity funds who start to back the winners of the venture capital portfolio; bank and debt market lenders derive comfort from the institutional investors and more predictable cash flows of the underlying projects. Over time, entities can get listed in the wider public market and more mature, yield seeking investors can come into finance the debt. This graphic indicates proportions: the quantum of capital deployed in a more mature industry is far higher than with the start-ups.

Pulling the right levers

As can easily be identified, different capital providers have varied and divergent considerations when it comes to investing. The industries and financing structures go through stages of investment opportunity creation, pooling in more local capital, and finally, the emergence of long-term capital providers in the cap table for takeout financing.

Policy levers need to consider these various stages which evolve with the maturity of industry and types of capital providers. Green finance currently gets bundled into one set of regulations with similar rules and expectations, for example, around disclosures, mandates, and targets. The intensity of regulations needs to be commensurate with the maturity of the industry and the ability of the capital providers to address the requirements. This will also allow the regulators to help shape the industries required in India’s march to Net Zero by 2070.

Akhilesh Tilotia, the author is with the National Investment and Infrastructure Fund Limited. Views are personal.