The Global India Insights series is a journey to understand global capital flows, what drives global institutional investors investment decisions, their implications for India, and its impact on the investment environment.

In my first two columns, I wrote about the Global Reset – How Trump’s Tantrums will lead to rebalance of global portfolios and how India can attract USD 200 billion in this reset.

In the next two, I set context to that flow by showing how foreign investors are anyways under invested by a trillion dollars in India. In that, of the investments they have made, I speculated that foreign investors are rolling the dice on their India investments.

I then began detailing whether Foreign Investors are indeed exiting India – from the FDI perspective. And wanted to discuss the same from the portfolio investors perspective. However, I will cover that in a future column and move focus to the shocking developments on the US-India trade relationship over the last week.

Decoding Trump tariff

I am writing this on the 7th of August, 2025. Now, this is important, as in Donald Trump’s world, by the time you read this over the next few days, the entire context could have changed.

As it did in the last 7 days itself.

On 30th July, Trump slapped a 25% tariff on Indian exports to US, effective from August 7th, citing unhappiness over the trade negotiations and warned of a penalty rate for India’s continued purchase of Russian crude oil. On 6th August, he threatened to make it 50% by August 27th if India does not cease its Russian oil purchases.

There were reports in mid-July suggesting that the trade negotiations were going great and that India may walk out with a 15% tariff rate.

It is difficult to see how we reached a situation where we have 25% tariff + penalty. It should be deeply disappointing for the government, the trade negotiators and the foreign policy officials to have ended in this situation.

Especially, given our starting conditions going into the trade negotiation.

India should not have been ‘Trumped’

On the day, Donald Trump won the US elections in November, I wrote in an opinion piece for a financial journal, that India may be a net beneficiary of Trump’s ‘America First’ policies.

I noted that other competing countries were vulnerable to Trump’s stated policies, whereas the Indian state and Indian Corporates did not have:

- Commodity like oil, where the US seeks to control prices. Eg: Saudi, Russia

- High technology industry, such as chips or AI, where the US seeks dominance. Eg: China/ Taiwan/ EU

- Large trade surplus with the US that could invite tariffs. Eg: Mexico, Vietnam, China

- Dependence on US foreign policy for regional conflicts. Eg: Israel, Middle East, Ukraine

I believed that this would offer India some leverage to try and enter a bilateral trade on favourable terms. India could also potentially offer to buy US shale oil and Gas and wean away its purchases from Russia.

More importantly, I termed Trump, a ‘messiah’ for Indian trade and investment.

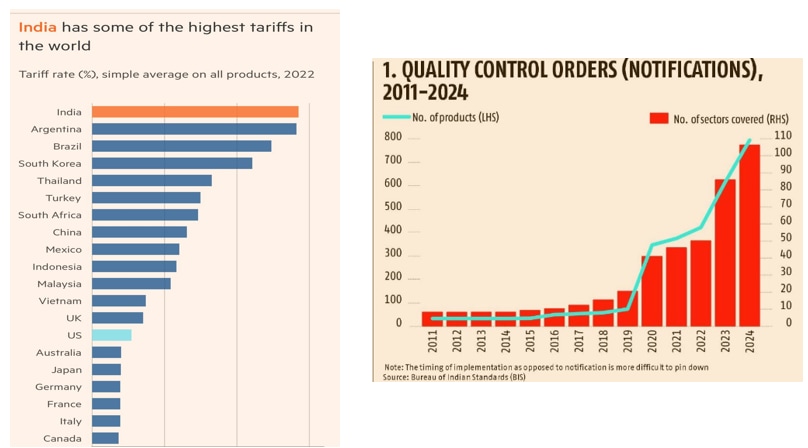

India has indeed increased import duties over the last few years in its quest of ‘Atma Nirbharta’ – self dependence and to promote ‘Make in India’. Apart from duties, true to India’s bureaucratic licencing and permit raj system, it also notified many more products to meet the Quality Control Order (QCOs) – a means to curb imports.

My hope was as India enters bilateral trade negotiations with the US, we would have to reduce duties and dismantle the quota systems to get favourable treatment and access to US markets. And once you do that for US, India can replicate and do the same for other high income, developed world countries like the EU, UK, Japan, Canada, Australia etc.

This is why I termed Trump a ‘messiah’. Someone who would force India to open again to global trade and investment.

Since the 1990s, this is what helped India attract global capital from corporations and investors. It is what helped Indian industry to compete and succeed in global markets. This is what boosted our growth rate.

But here we are, as of now.

Forget about favours and a trade deal.

We have a potential 50% tariff rate on goods exports to US.

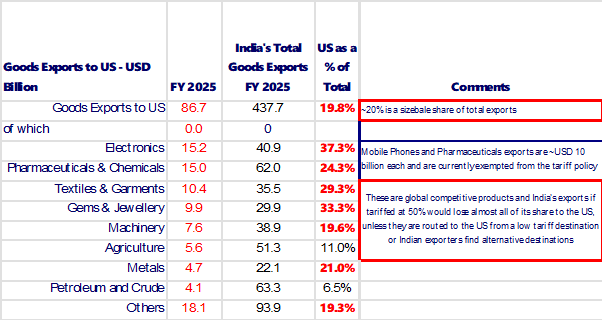

At the 25% tariff level, we could have yet competed, as other similar competing trade nations also have tariffs around the 15%-25% level. So, not ideal but manageable.

However, if the tariff rate remains at 50%, very close to China’s tariff rate, a large share of the Indian exports to the US will be uncompetitive.

Economists estimate that the total impact on India’s GDP if a significant part of US exports is lost would be ~0.5% of GDP.

That might not sound a lot, but the way to look at this, is what would have been possible if India actually got a ~15% tariff deal and a preferred country status. Imagine the boost to India trade and the likely increase in investments to support the increased trade.

Trump, as I have noted above, presented India the opportunity to scale up on global value chain and boost India’s global trade, investment and growth.

What should be India’s approach?

Can and should India remedy this? There are reasons put forward for the dramatic turn of events

- India did not agree to US demands on opening up India’s farm trade and defence purchases

- Trump wants to solve the Russia-Ukraine problem and sees India’s purchases of Russian oil as a big aspect of funding Putin’s war efforts and hence the penal rate

- Trump did not like the fact that India kept refuting his insistence that he solved the India-Pakistan conflict

Whether we can, depends on the concessions, sacrifices and compromises we are willing to make for demands which seem unjust and inappropriate.

And with Trump, we do not know what is coming next.

We should remedy, given US’s importance in the global economy, trade and investment.

India and US are connected in many ways.

India received USD 32 billion from its diaspora in the US as remittances.

India’s services exports (USD 387 billion), of which especially IT and business services (USD 290 billion, a major share of that is to the US.

Many US corporations have their global capability centres (GCC) in India. Most of the corporations would also look to expand their sourcing and presence in India.

US residents and institutions are large investors into the Indian equity and bond market. The US Federal reserve data shows ~ USD 350 billion of US resident money invested in Indian capital markets.

Similarly, US institutional investors have investments in private equity, venture capital, real estate and infrastructure assets in India.

And these numbers, as you would realise from my earlier columns in this series, are despite India being under invested by these global investors and corporations.

India must ensure that such situations does not make India ‘un-investable’ from a geo-political risk perspective.

India should always retain its sovereignty and not bow down to threats and intimidation; however, we should find ways to placate the situation as there is lot to gain for India in having a favourable relationship with the US, which it has worked on to improve since 1990s.

Disclaimer

Arvind Chari is a Chief Investment Strategist and has been with Quantum Advisors India group since 2004. Arvind has over 20 years of experience in long-term India investing across asset classes. Arvind is a thought leader and guides global investors on their India allocation.

This article is for educational and discussion purposes only and is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any investment in any jurisdiction. No advice is being offered nor recommendation given and any examples are purely for illustrative purposes. The views expressed contain information that has been derived from publicly available sources that have not been independently verified. No representation or warranty is made as to the accuracy, completeness, or reliability of the information.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are my personal views and should not be construed of the Firm. There is no assurance or guarantee that the historical result is indicative of future results and the future looking statements are inherently uncertain and cannot assure that the results or developments anticipated will be realized.