With the advancement of internet and rapid increase of online publications, reading habits have taken a drastic turn. Even when one reads long-form articles online, they are customised for today’s readers, with short, sharp sentences and simpler words and slangs to increase readability. This has directly affected the publishing industry too and the way literature is being written nowadays. A consequence of our tech-advanced times? Maybe.

New Delhi-based journalist Aritry Das, who studied comparative literature, calls herself a victim of this socio-cultural behavioural change. “I used to be a voracious reader. These days, I can hardly keep up with my personal reading list. As I work in online content creation, I read things online a lot and it affects me even more,” the 26-year-old says. Das believes that the medium of reading is also changing. “People are increasingly switching to e-book readers instead of paperbacks and hardcover prints that we used to treasure earlier,” she adds.

Mumbai-based media professional Modhusree Das agrees. “I still read books, but not as much as I used to… just enough to keep up. Also, I have sided with electronic versions as they are much easier to access,” says Das, who misses having conversations with people over a book and a cup of tea or coffee. “I see people discussing the latest movies and TV series, but books? Not so much,” the 26-year-old says.

READ ALSO | 5G services to be rolled out by 2020; $70 billion investment seen

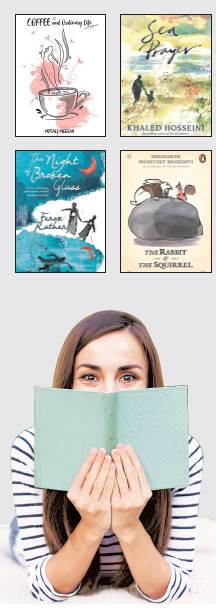

Perhaps it’s because of readers like these that writers like Khaled Hosseini are experimenting with the length of the book. His latest, Sea Prayer, which was based on the refugee crisis, was under 48 pages long and was accompanied by watercolour illustrations. Interestingly, despite the book being of unconventional length, publisher Penguin Random House labelled it ‘literary fiction’, clearly implying that the definition of the novel is changing.

However, bear in mind that this is not a recent phenomenon. The Little Prince, published in 1943, was all of 112 pages. But till date, it has been translated into more than 300 languages and has been a bestseller over the years.

One also has to keep in mind the fact that publishers and writers today have to compete and keep pace with online video-streaming services such as Netflix and Amazon as well, which have given birth to the culture of binge-watching. In such a scenario, narrative-driven literature suffers the most because consumers now have more ‘exciting’ audio-visual telling of stories in the form of TV series. “People these days don’t even have enough patience to watch a film that is longer than two hours, let alone read a book,” says Aritry Das.

Siddharth Dhanvant Shanghvi, author of The Rabbit and the Squirrel (2018), a 59-page book on love, loss and friendship, agrees that the average reader’s attention span is quite short these days. “Fewer people are reading. The quality of attention is scattered, diffused,” says the author, whose recent books show a change of aesthetic from his first. Shanghvi wrote his first The Last Song of Dusk (2004) when he was just 22 years old. According to him, there was excess fat in the book. At present, the writer is drawn to formalism and to essential, small, concise and clear works of art, literature and music.

Shanghvi says he had grown cynical about the idea of publishing and the larger culture around it, but publishing The Rabbit and The Squirrel reminded him that fiction was never the mainstay of scale, but of depth. As per him, readers are evidence of depth. This is also why he never thought to publish this book, although he wrote it five years ago. “But I’m so glad I did. I have felt so absurdly loved because of this book and I feel nothing but profound gratitude for readers who, in gifting me their solitude, allow me to nurture my own,” he states.

The long haul

In case of certain books, however, one can’t help but go for a longer length, especially if one has to flesh out characters, and build side stories and twists. Vish Dhamija’s fast-paced thrillers Bhendi Bazaar, The Mogul and Deja Karma are some examples. Dhamija has a different point of view when it comes to the reader’s attention span. He believes that the online episodic content offered by platforms like Netflix and Amazon helps consumers (and readers) get used to the idea of longer stories and screenplays unlike, say, a film, which is a mere 180-minute affair. “So the attention span isn’t necessarily decreasing if people are willing to watch a 10-part series and then wait for the second season (Sacred Games being a case in point), but yes, the story has to be engaging and the authors need to grasp readers’ attention from page one,” he says.

For a genuine reader, too, the charm of holding a book is still untouched by any new trends. People with a passion for the written word still take out the time to read and engage with a good book regardless of its length. Delhi-based 27-year-old Samudraneel Gupta, a student of literature and culture studies, says, “I have always been able to combine pleasure and sincerity when it comes to either reading a book or watching a show. I am trained to treat any text, whether it is written or visual, critically and with compassion… I do not see any difference between watching a long series or reading a long book and they do not come in the way of one another precisely because I do not necessarily place one over the other, but engage with them equally.”

Then there are writers like Satyajit Sarna who have written both novels and poems. Interestingly, Sarna doesn’t consider his book The Angel’s Share (2012), which is 244 pages long, to be a moderately lengthy read. “When I think of a long read, I think of Bleak House or Infinite Jest or Ulysses. The Angel’s Share, I am told, is a really quick read… I was disappointed to hear that! I thought if I had poured so much heart, soul, angst and vinegar into a book, then surely, it would occupy readers longer than a few hours,” says Sarna, who disapproves of comparing a novel with a collection of poems. “I don’t think it’s fair to compare novels with poems. They come from such different places,” says Sarna, who isn’t bothered about Netflix or Amazon hampering readership. “A good book is as long as it ever was, and as engrossing. Those lengths have stayed more or less similar to what they were before. But I do agree that readers of the written word are getting thinner on the ground. Fewer people will read words in the future, and more of our information will be imparted visually.”

For this, he blames the smartphone. “I think the biggest enemy of coherent thinking is the smartphone. We dissipate a lot of intellectual energy on atomised prompts and pursuits. As a test, ask yourself, how many of your notifications could you have ignored today without causing anyone any grave loss?” he questions.

Short & sweet

There are some authors, however, who are making a conscious effort to offer short content. Mitali Meelan’s Coffee and Ordinary Life (2017), a collection of short poetry, can be flipped through and finished while having a cup of coffee. “But novels are meant to steal your sleep and suck you into a world you don’t want to leave. So the length depends on the purpose you want your books to serve,” says Meelan, who wanted readers to enjoy the prose as much as the story in A Long Way Home (2018), which is why it’s thicker than The Guest (2016), which is a quick read. “I don’t let the length decide my story while I’m writing. What works for a story has to be in there. You just need to be mindful of the words you choose and get rid of anything that doesn’t move the plot forward,” she says.

Another author writing short content is Adithi Rao. Her debut novel Left from the Nameless Shop (2018) comprises short interconnected stories. Sceptics might argue that Rao and her publisher were playing it safe because she is a first-timer, but Rao disagrees. “People often think that with shorter attention spans of today, short stories have a better chance of being read than novels. But I’m not certain the two are necessarily interchangeable,” she says. As per Rao, some stories need to be narrated in depth, for which they need the luxury of words, whereas others might be best told with brevity, succinctly and with a powerful ending that is best reached quickly to be most effective.

Publishers’ perspective

This tussle between short versus long reads is one that publishing houses in the country have duly taken note of. “One thing that we need to keep in mind as publishers is that we publish increasingly for readers who are more accustomed to and prefer short-form reading, thanks to the easy availability of books and journalistic literature on smartphones and digital devices,” says Udayan Mitra, literary publisher, HarperCollins, which has some excellent writing in the form of novellas and short story collections—the publisher published two successful short novels, Janice Pariat’s The Nine-Chambered Heart and Vikram Paralkar’s The Wounds of the Dead, as well as some wonderful short collections, including Akil Kumarasamy’s Half Gods, Jayant Kaikini’s No Presents Please and Feroz Rather’s Night of Broken Glass, last year.

But they have long-form writing as well. In 2018, they published Shubhangi Swarup’s Latitudes of Longing, which has found a lot of appreciative readers. The book runs to 350 pages and is something of a multifaceted saga, but Mitra doesn’t think the length has put any readers off. “It really depends on the subject matter. If it’s, let’s say, history of modern India, I would expect the book to run to say 600-plus pages. Similarly, in fiction, a generational saga can be expected to be 400-plus pages. In neither case would I be looking for a 200- to 250-page book,” he says, adding, “That said, I do strongly support the dictum, ‘Brevity is the soul of wit’. We live in busy times when people have a thousand things to do, as well as read books, so it’s important to stick to the point and be as concise as possible when writing a book.”

Mitra believes there is a ready readership for both longer and shorter formats. “One of the interesting phenomena I’ve noticed is that airport store sales constitute a fair percentage of the number of copies serious non-fiction (which often runs to 500-plus pages) sells. I find this interesting because people are obviously not looking to read and finish a 500-page book on a flight, but they buy it at the airport store nevertheless,” he says.

When it comes to short reads, though, a big plus is the price factor. Typically, a 200- to 250-page book is priced much lower than a 500- or 600-page book, and a reader not willing to spend a higher amount may prefer a shorter book. Interestingly, at publishing house Juggernaut, every contract mentions a word length based on what they estimate is the necessary word length to tell the story. However, it’s only indicative and much changes at the time of writing and editing. “Our commissioning is often very event- or news-driven and so we do have a tendency to commission shorter books for that reason… also because we like to produce them quickly,” says Parth Phiroze Mehrotra, non-fiction commissioning editor, Juggernaut Books.

It’s no surprise then that the top three or four of Juggernaut’s all-time hits are under 40,000 words. The publishing house, however, maintains that length isn’t their sore concern—the books have to be good and readable. But overall, they have noticed that shorter, tighter books do better. And for this reason, they prefer books that are tightly edited, lean, where the pace of the narrative doesn’t flag and where the reader isn’t inundated with an unnecessary avalanche of information. “A flabby flatulent book or an incomplete dissatisfying book… both would impact sales and reviews,” asserts Mehrotra.

Praveen Tiwari, publishing head, Bloomsbury, too, asserts that people look for shorter books, which they can finish while travelling on a flight or train. And that’s why Bloomsbury also prefers shorter books, provided the author can do justice to the subject.

Poulomi Chatterjee, publisher and editor-in-chief, Hachette India, believes the length of a book is completely dependent on the genre, the topicality or appeal of the book and it being appropriately priced for the genre in the Indian market. “The preference is for books that are between 200 and 300 pages, which, depending on the page setting, can be anywhere between 40,000 and 80,000 words. The page extent determines the price of a book, of course. So to price books appropriately in particular genres, we would need to ensure that the number of pages is within a certain limit,” she says, adding, “For instance, if it is a comprehensive narrative history book, a good publisher would not want to compromise on the content and it could easily run to over 400 pages. Literary fiction titles have no determined length, though for commercial fiction titles (romance, for example), a shorter, pacier narrative is preferable.”

Other publishers resonate her view. “A serious research-oriented work on history or a thriller normally works well with a slightly higher word count of around 100,000 words, while children’s books normally would have a lower word count,” says Milee Ashwarya, publisher, Ebury Publishing and Vintage Publishing from Penguin Random House India.