For Delhi-based Krishna Loomba, planning a vacation is not easy. She has to check whether the tourist destination that she is visiting is wheelchair friendly and has accessible features like ramps, railings, flooring and even toilets. Loomba had developed a spinal deformity when she was in her 10th grade and since then, she has been immobile. Today, at 25 years, she performs Bollywood-style dance numbers in wedding functions, does daily chores and works at an NGO for a living— all while sitting on a wheelchair.

Loomba and other persons with disabilities (PwDs)—or even senior citizens, children and specially-abled people, for that matter—have remained at the margins for years to be holistically included into the accessible tourism sphere.

But what exactly is accessible tourism? According to the draft version of the ‘Accessible Tourism Guidelines’ issued by the Union ministry of tourism last year, accessible tourism refers to the concept of making the experience of tourism universally accessible and inclusive for all by creating information, infrastructure and services friendly, safe and welcoming. It “does not imply merely tourism for the persons with disabilities, rather an experience that caters to the needs of all thereby enhancing the economic potentials of any tourist place or region”, the guidelines add.

So what does it take to make a tourist destination accessible? Is there a stigma related to disability? Is it not a big market for businesses? Or is there a need to make arrangements of accessibility in public places just for the sake of compliance?

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 15% of the world’s population (1 billion people) live with some form of disability. The corresponding figure for India is 2.1%. No wonder, the country is inching towards an all-inclusive approach to boost tourism and create a friendly environment in tourist places. Efforts are now being made to make Indian cities and tourist destinations inclusive, accessible and barrier-free.

For instance, in a recent session of Parliament, Union road transport and highways minister Nitin Gadkari stated that only 61 state transport undertakings (STUs), which are members of the Association of State Road Transport Undertakings (ASRTU), are operating 1,45,747 buses and 51,043 of them are equipped with facility for boarding and deboarding for disabled persons. This means India has 12 state agencies which don’t have buses equipped with facilities for PwDs.

The Union ministry of tourism is also finalising its new tourism policy with new accessibility guidelines. “We are making a consolidated tourism policy and accessible guidelines are included in the policy. We have invited comments and suggestions from different sectors to work on the same and finalise soon. The much-awaited new National Tourism Policy is at the concluding stage of processing and will soon be placed before the Union cabinet to seek the final nod,” Union minister of tourism G Kishan Reddy told FE.

Naturally, the stakeholders concerned are quite optimistic. “Accessible tourism advocates easy access to all facets that facilitate a tourist. Right from the time he or she alights from a mode of transport to the accommodation to sightseeing or visiting a restaurant till departure, a strategy for responsible and sustainable tourism is needed that caters to the local community and provides a holistic view point. While the tourism policy takes shape, in our effort to support this, we have communicated to our members to take note of all important steps in their operations,” says Rajiv Mehra, president of the Indian Association of Tour Operators, (IATO), an apex body of inbound tour operators in the country.

However, for the act to translate into action, the guidelines are to be adhered by different sectors. Gaurav Raheja, professor and head, department of architecture and planning, professor incharge of inclusion and accessibility services, Indian Institute of Technology (IIT)-Roorkee, finds tourism is a complex phenomenon. “Constant support is required from diverse sectors and stakeholders to translate the vision of accessible tourism to an inclusive one.”

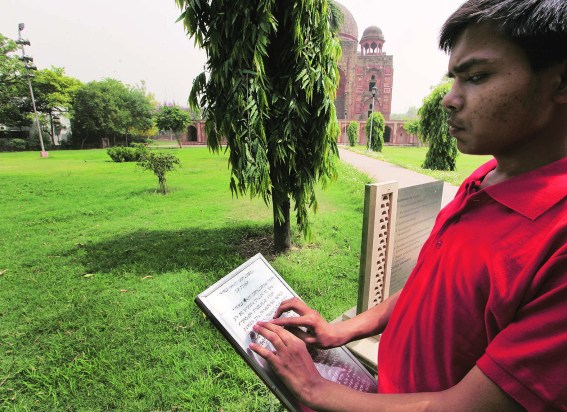

Raheja has drafted nine chapters and one appendix of the ‘Accessibility Guidelines for Tourism’, which cover maps, websites, signages and multilingual information. It is an attempt to unite the key aspects of tourism with an accessibility perspective allowing an intersectoral dialogue and understanding. “Inclusive mobility, infrastructure and accessibility, if followed, can add to the economic perspective of the country,” adds Raheja.

Raheja quotes an example to make his case for religious tourism. “Such places must have a resting space for the elderly, or a queue management system, just like banks, where a token can be provided for darshan of deity,” he feels. If one room in a hotel is universally accessible, all the other rooms must have adaptability to adjust accessibility, he adds.

“Accessibility as a lip service doesn’t mean inclusion. It is a 24×7 operation and must become the DNA of every industry. We should be able to curate tactical campaigns which impact tourism and accessibility. The experience only gets better with sign boards in at least universal language along with the local languages, or feature QR codes that on scanning will provide detailed information about the monument, its history and other details in that particular language. Integration of digital methods as alternative information systems and tools for sharing feedback / lodging complaints is a must,” he says.

Similarly, roads must have an extensive network of complete streets to enhance accessibility, safety and mobility. Most Indian cities have non-segregated vehicle lanes, narrow/encroached footpaths by hawkers, vehicles. Pedestrians are often ignored in road design with missing sidewalks, inappropriate curb heights, and infrequent road crossings. “A street redesign is not just about beautification, it is about creating safe and convenient streets for all users,” adds Raheja.

For instance, Chennai and Pune have an extensive network of complete streets to enhance accessibility and mobility. Another example of higher degree of accessibility is Mumbai’s Marine Drive which means the space is walkable and wheelable, where the city’s rich and poor can interact. The redesigned Chandni Chowk in Delhi includes greenery to combat pollution, transform bottlenecks, wider footpaths, and has rainwater harvesting structures.

All-inclusive approach

Organisations are now implementing an approach to sensitise stakeholders to understand the diverse needs of persons with disabilities and other people as tourists through a prism of universal design. For instance, pelican signals can help prevent traffic accidents and save pedestrians. These signals are manually controlled. Pressing the button gives the pedestrian a window of 15 seconds to cross the road safely by turning the signal to red. In India, cities like Bengaluru and Hyderabad have such pelican signals.

Just as hotels and transit stations should provide facilities such as power-assisted doors, handrails and wheelchair ramps, they must be accessible digitally to people with vision, hearing, mobility and cognitive disabilities. Travellers with disabilities face many barriers when planning, booking and going on a trip, whether for business or pleasure. For example, a kiosk for printing boarding passes that lacks a pinch-to-zoom feature can make it difficult for people with poor vision to check in for their flight.

“I believe that businesses cannot survive without going digital, and stand to compromise on their growth and image if they fail to empathise, invest in and practice inclusivity and accessibility,” says Manish Gupta, founder and CEO, TestingXperts, a software testing provider assisting organisations to deliver high quality software applications. The company works with global travel and tourism organisations to help them ensure their apps are built in a manner where they are compliant with industry-wide accessibility guidelines.

Gupta shares a few references. People with disabilities may face unnecessary challenges while researching and booking travel, such as websites and mobile apps that can’t be read by screen readers, information contained only within images, video and audio content without transcripts, forms that can’t be filled out using assistive technologies or PDF files with too-small text that won’t enlarge.

“We make applications accessibility compliant as per Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 guidelines. The team checks compliance across a variety of areas like colour contrast, screen reader operations, assistive device operations, etc, with a user focused approach. This makes it easy for any disabled person to book tickets through the portal,” he shares.

Post-Covid, theatre chain PVR INOX has been working aggressively on increasing the number of accessible cinemas.

“Currently, we have 212 accessible cinemas that constitute over 58% of the total cinemas. Of these, 25% have been made accessible with assistive equipment that require the user to seek on-ground assistance. Our staff have been trained and sensitised to assist people with special needs,” says Gautam Dutta, co-CEO, PVR INOX.

Meanwhile, heritage and art event stakeholders are working towards making monuments accessible. Some of these include Mehrangarh Fort in Rajasthan, Kolkata Centre for Creativity, Delhi Art Gallery in Delhi, India Art Fair, Serendipity Arts Festival and Kochi Biennale, among others.

Mumbai-based heritage architect and access consultant Siddhant Shah, who has worked on projects to create tactile artwork and comprehensive Braille books, has collaborated with stakeholders in this regard. Under ‘Access For All’, Shah’s organisation bridges the gap between museums, arts and disability with a focus to provide physical, intellectual and social access at sites of cultural significance.

“Can you imagine the impact on the economy if over 60 million people are not travelling due to a disability,” asks Shah, who has worked at the City Palace Museum in Jaipur on aspects of accessibility—physical access, construction of disabled-friendly toilets and enhancing the “touch and feel” of the place by creating tactile artwork and Braille renditions.

“We created ramps, accessible toilets with all the facilities, and finally, the one revolutionary thing that we brought in was making cultural heritage sites accessible for persons with visual impairment. That’s where an entire range of tactile artwork came into place so that the visually impaired people could touch and feel the paintings and the maps of the old city of Jaipur and understand what the grid-based system means, where the palace is located, how it is placed in Jaipur, what are the geographies around it, etc,” says Shah.

What does India lack?

India requires a change in perception more than just resources to take the concept of accessible tourism forward. “At times, silent airports may pose a hurdle for the visually challenged, if travelling alone. So, there needs to be a strategy for responsible and sustainable tourism that caters to the benefit of the local community. The challenges emerge from the behaviour of a tourist, over tourism neglecting the carrying capacity of a tourism product/destination,” adds Mehra of IATO.

While awareness is still a challenge, budgeting is a big problem. “Everybody thinks it’s expensive, but we retrofit accessibility. A lot of people continue to associate disability with charity. There are art galleries in Mumbai whose management told us that they would provide a one-time donation, but do not want persons with disabilities in their gallery. There’s no maintenance of the ramps or other access facilities. We don’t have a set of consolidated action plans or strict rules for accessible tourism in the country,” says Shah, who feels that public space is one where one doesn’t have to put in additional efforts to be a part of that spatial planning. “There is a need to involve the stakeholders, move beyond the ableism-based approach, and bring in accessibility experts and consultants from various departments—health, maintenance and services,” adds Shah.

Raheja feels India lacks orientation. As long as people think facilities are only for the disabled and stay disconnected from an all-inclusive approach, no matter how much investment is made, it won’t work. “With accessible clean drinking sprouts one should know how to have water and leave the space clean; to build ramps with the wrong slope, or build toilets which are inaccessible. It’s a shift in perspective and the shift will happen when more sensitisation will happen,” adds Raheja.

For infrastructure to be inclusive, the country needs to lead by example to first accept the attitudinal barriers that exist around disability and then work on incorporating the principles of universal design, both in theory and in practice.

“Designing accessible spaces presents a huge opportunity to include PwDs, who have been reported to have a total global purchasing power of $8 trillion, in eventually contributing to the national economy. By approaching ‘accessibility’ as an opportunity, India can help translate the promise of ‘leaving no one behind’ into action,” feels Arman Ali, executive director, National Centre for Promotion of Employment for Disabled People (NCPEDP), a non-profit organisation working for the empowerment of persons with disabilities.

As per Ali, implementation of the accessibility guidelines, as mentioned in the Right for Persons With Disabilities (RPWD) Act, is a challenge. “Disabled people still do not have proper awareness about their own rights and hence are unable to demand for adequate measures to be taken that will help their participation in society.” Last year, the NCPEDP installed ambulifts at 20 airports in India as part of the Accessible India campaign which aims to make travel and commuting easier for people with reduced mobility.

Under the campaign, 35 international and 55 domestic airports have been made accessible. Forty-one airports are fully equipped with aerobridges. Clearly, initiatives like these help disabled people in becoming a critical part of the mainstream economy and social structure.