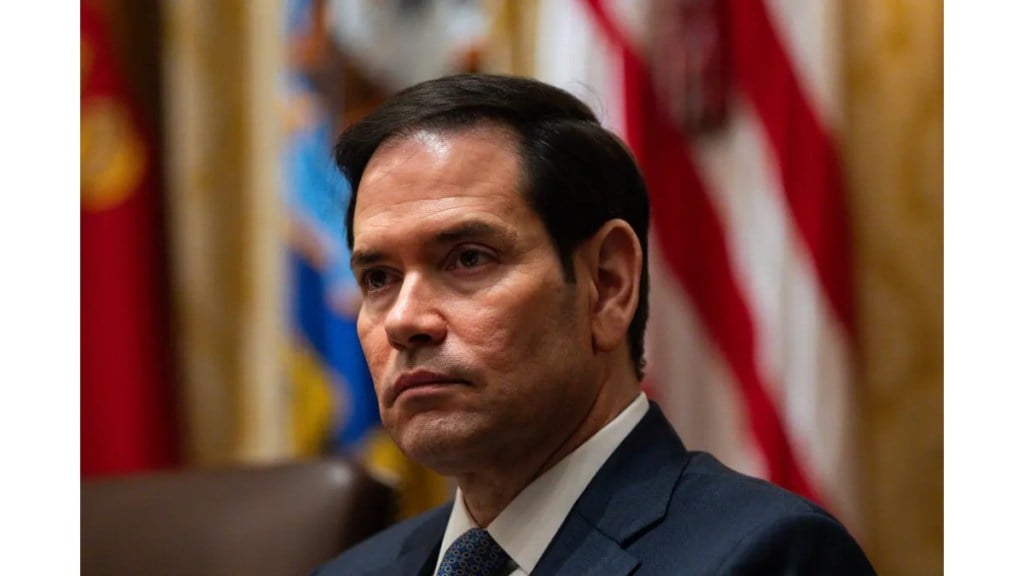

On December 9, US Secretary of State Marco Rubio issued a directive that instantly captured public attention far beyond the bureaucracy of Washington. The US State Department would stop using the sans-serif Calibri font and return to Times New Roman for official and diplomatic communications. Rubio described the earlier switch, made in 2023 under the Biden administration, as a “wasteful diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility (DEIA) move” and said Times New Roman better conveys the formality and professionalism expected of US documents.

The move has been widely framed as part of a broader rollback of DEI initiatives across federal agencies.

In 2023, then-secretary of state Antony Blinken had directed the state department to adopt Calibri, a contemporary sans-serif font, as its default typeface with the rationale of making diplomatic correspondence more accessible to people with visual disabilities and aligning with modern digital readability standards.

From Aesthetics to Ideology

At first glance, this debate over fonts might seem almost trivial, but it underscores how typographic choices can become symbolic flashpoints in larger ideological battles. Typography isn’t just about aesthetics. It touches on accessibility, tradition, identity, and the meaning of official representation. This debate touches on how institutions represent themselves, who is prioritised in design decisions, and how subtle features of communication can signal deeper values.

Typography and scripts are fundamental to how we communicate in written form.

In a globalised digital world, readability, accessibility, and visual identity matter to millions who interact daily with documents, websites, and official communications. Choices about fonts can affect legibility for people with disabilities, influence how institutions present authority, and become proxies for larger debates about tradition versus modernisation.

Moreover, some historical examples show writing systems and typographic standards have been leveraged as instruments of cultural policy and nationalism. Serif fonts like Times New Roman, with their small decorative lines at the ends of strokes, can be hard to read on screens and for some readers with dyslexia or low vision.

A Global History of Script and Political Control

The US font fight isn’t the first time that typography or writing rules have been altered for ideological, cultural, or political reasons. One of the most dramatic examples of enforced script change came in the early 20th century with Turkey’s alphabet reform. In 1928, under the leadership of field marshal and statesperson Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Turkey abolished the Arabic-based writing system used for centuries and adopted a Latin-based alphabet. This was part of Atatürk’s broader modernisation programme aimed at secularisation, boosting literacy, and aligning with Western norms.

The transition was rapid and state-mandated. Teachers were trained, schools restructured, and new educational materials produced. But it also sparked resistance from religious conservatives and traditionalists as severing cultural and historical continuity, especially with religious texts traditionally read in Arabic script. The reform dramatically increased literacy rates but remains a reminder of how script choices are deeply tied to cultural identity.

Meanwhile, in the Soviet Union, entire scripts for minority languages were changed across decades as part of state language policy. In the 1920s, many Turkic languages adopted Latin-based alphabets to improve literacy and break ties with Islamic and Arabic traditions. Later, in the late 1930s and 1940s, the same scripts were systematically replaced with Cyrillic alphabets to strengthen linguistic ties to Russian and reinforce centralised control. These changes weren’t practical, but affected identity, education, and cultural preservation.

In early 20th-century Germany, a fierce typographic struggle known as the Antiqua-Fraktur dispute pitted traditional blackletter typefaces like Fraktur against more Latin-style Antiqua fonts. Blackletter had been widely used in German-language texts and was seen by many nationalists as a marker of German cultural identity. Some argued that Antiqua was more modern, internationally intelligible, and suitable for science and global communication.

The dispute wasn’t resolved purely on design terms. The Nazis famously banned Fraktur in 1941, deeming it outdated and even referring to it rhetorically as ‘Judenlettern’ (Jewish letters). This dispute shows that font and script aren’t just technical choices but can become symbolic battlegrounds over political legitimacy.

Even familiar languages like German have seen relatively recent official reforms. The German orthography reform of 1996, which aimed to simplify and standardise spelling and punctuation across German-speaking countries, sparked a public debate. Many Germans resisted the changes, seeing them as unnecessary or intrusive, illustrating how even small updates to writing rules can stir passionate public response.

In various parts of the world, such as the Hangul simplification movement in Korea or orthographic reforms in Indian regional scripts, the push to simplify writing systems for education, technology, or modernisation often intersects with nationalism, cultural heritage, and regional identity.

For instance, the Hangul Simplification Movement in South Korea (1949-1955) was a push by President Syngman Rhee’s government to create a simpler Hangul orthography, but it faced strong public opposition and failed, leading to a return to the established system, though it highlighted desires for easier literacy.

Another prominent example of a government-mandated orthographic reform is in the Malayalam script, which traditionally had over 1,200 unique graphemes, including many complex, fused consonant-vowel ligatures. After the 1971 reform, the Kerala government adopted a ‘reformed script’ or puthiya lipi. Among a few other changes, the total number of graphemes were reduced to a set of around 90 characters, simplifying printing and typewriting.

Earlier this year, in a pushback against the central government’s language policies, especially the new education policy’s three-language formula, which Tamil Nadu views as promoting Hindi, the Tamil Nadu government replaced the national rupee symbol in its state budget with the Tamil Roo due to language policy disagreements. The government of India mandates Noto Sans as the typeface for digital use for multilingual inclusion, while standardising on Unicode fonts for Indian languages to ensure interoperability, moving away from proprietary fonts.