This column is not about famous film stars. It is about how these stars have built their balance sheets. Abhishek Bachchan taught us restraint and repetition, the investor mindset inside a surname. Sonam Kapoor showed us how to monetise attention with social media. Danny Denzongpa reminded us that the quiet ones often own the most.

In the last edition of Bollywood Billionaires, we discussed how Juhi Chawla, Hindi cinema’s most beloved leads built an impressive portfolio away from public glare. Today, we feature Mohanlal, one of the biggest Malayalam movie stars.

In Vanaprastham, the most poignant scene is not the Kathakali performance.

It is what comes after.

Kunhikuttan is by himself, alone, backstage. The costume is still warm on his skin, the jewellery still heavy, the paint still thick. For the duration of the ritual, he was Karna, a tragic hero from the Mahabharata, worshipped, revered, transformed by paint, costume and tradition.

The audience has since gone back home. The oil lamps have dimmed. Backstage, Kunhikuttan begins removing the make-up that turned him into a god.

Mohanlal performs the moment without overt emotion.

Green comes off first. Then red. Then black. The divine face dissolves into the face of a man who has spent his whole life learning how to become someone else, because being himself was never going to be enough for the world around him.

There is no music to guide you. No release written into the moment.

The camera stays with him as colour leaves his face and divinity drains from his body. What emerges is not catharsis but something colder. Recognition.

It is perhaps one of the most uncomfortable scenes in Indian cinema because it refuses to flatter either the character or the audience.

That scene is why Vanaprastham sits at the centre of any serious conversation about Mohanlal. Not because it is his most popular film. Not because it has been feted around the world or was selected in the Un Certain Regard category at Cannes Film Festival.

The film is not an easy recommendation. It is slow, bruising. It demands your attention. It rewards you with discomfort. It asks a question we are trained not to ask.

What happens to a man when the world no longer needs him to be extraordinary?

For me this question quietly explains Mohanlal’s life. His acting. His choices. And most interestingly, the way he has handled money.

Fame is not wealth. It is volatility

Most fans misunderstand the secret that stars and wealth share. We imagine fame rains down money like confetti. The truth? Fortunes belong to actors who treat adoration like the stock market, volatile and requiring constant reinvestment.

Mohanlal mastered this decades ago.

“I have invested all my earnings in this film. I didn’t borrow money from anywhere. I invested what I have earned in this film,” he said in an interview on Rediff, about turning into a producer for Vanaprastham, because he believed in the story so much.

That is not a quote you give when you are playing to the gallery. That is a quote you give when you already know how this industry works, and you have decided that you would rather lose money on your own terms than be safe on someone else’s.

This isn’t Instagram wisdom. This is capitalism with clarity.

And it helps to remember that the man making these bets is not just popular, he is institutionally validated. The Government of India’s Dadasaheb Phalke Award press release describes him as having appeared in over 300 films, winning five National Film Awards, and receiving Padma Shri in 2001 and Padma Bhushan in 2019, before being named the Dadasaheb Phalke Award recipient for the year 2023.

That is not just decoration, this is credibility capital, the kind that keeps you investable for futures to come.

The villain who became a brand: Why Narendran still matters

Long before the industry called him a legend, Mohanlal and his friends were trying to make cinema happen with whatever they had. They shot an amateur film, Thiranottam, full of youthful certainty, and then watched it get stuck with the censor board for decades.

His journey could have ended right there, in a half finished dream in 1978.

This was a brutal first lesson: you can do the work and still not control the gate.

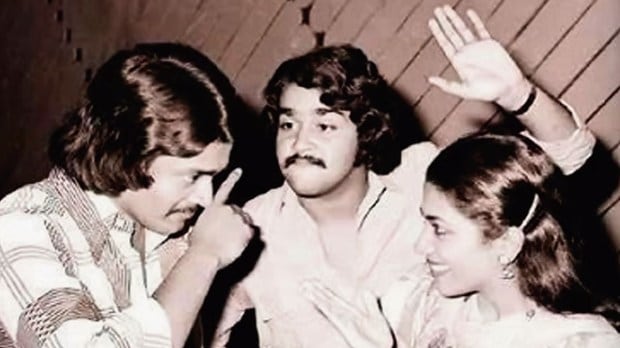

It wasn’t until 1980, when the legendary film studio Navodaya put out an audition call for a film. Manjil Virinja Pookkal had debut energy everywhere. Fazil behind the camera. Shankar and Poornima Jayaram as leads. Jerry Amaldev on music. The film was being built as a launchpad for the next generation.

And then there is the villain, played by Mohanlal.

In the audition room for the role, three panellists gave him single digit marks out of 100, basically a polite rejection.

Director Fazil and Jijo Punnoose overruled them, scoring him in the nineties because Fazil wanted a villain who looked shy on the outside, not a stock brute, which was the norm at the time.

In a film designed to mint a brand-new romantic hero, the audience walked out of the theatre talking about the antagonist. Narendran, played by Mohanlal, is not a cardboard bad man. He is cruel, yes, but charismatic. Menacing, but magnetic.

It is the first glimpse of Mohanlal’s unfair advantage: he does not need the spotlight to dominate a room. He can emerge from the shadows and still walk away with the film. Forty-five years later, that instinct still explains the career.

What separates Mohanlal from other actors is not “acting” in the capital A sense. He is not method. On screen, he simply becomes.

That is what audiences recognise in him, not performance, but possession. A miraculous shift that happens the moment the camera starts rolling.

It helps that Mohanlal’s foundation is not only cinematic. He comes from a disciplined middle-class Thiruvananthapuram household. Before films, his body was trained for combat and control.

He was serious about wrestling, winning state-level titles as a young man, learning how to stay calm while someone tries to pin you down. That calm shows up later as craft, and then as strategy.

The scale of his work is almost absurd. Over 400 films across his career. In 1986 alone, 34 of his films were released. For most actors, that is a lifetime. For him, it was one year.

Today, within Malayalam cinema, Mohanlal is priced like the ceiling. A Deccan Chronicle piece reported in May 2025 that he is at a Rs 20 crore plus fee for big ticket film projects, and that for major action entertainers his fee can go up to Rs 15 crore or more, while mid scale films can sit around Rs 5 to Rs 6 crore.

And while these fees are still speculative rather than openly disclosed, the Central GST Department recognising him as the highest GST paying actor from Malayalam cinema for FY 2024 to 25 gives you a cleaner proof that his earnings operate at the very top end of the market.

The Gulf strategy: Monetizing the ‘other’ Kerala

If you want to understand why Malayalam superstars have a different relationship with money than many Hindi film stars, you have to start with geography.

Kerala in India is not the only Kerala.

There is another Kerala stitched across the globe, especially in the Middle East. A working population that carried the language and the cinema habit with them.

The audience moved, but the demand did not. In fact, it got richer, because the Gulf version of your audience often has a sharper appetite for home than the audience that never left.

This matters because the smartest business bets in Malayalam cinema often sit on the same insight. Build for the travelling Malayali. Not just for the local Friday.

In an interview, he says it without drama: “The main markets for my films are the Middle East, US and Europe. Our films might not do well at the box office in Kerala, but could do well in these markets.”

So when he builds a consumer brand, he does not start by asking what sells in Kochi. He asks what sells in Dubai.

This is not just a creative choice, this is distribution thinking.

Small market does not mean small money, it actually means targeted money. For context The Kerala Migration Survey 2023 estimates total remittances to Kerala at Rs 216,893 crore in 2023. That is up from Rs 85,092 crore in 2018.

The Keralite living outside the country is an economic engine, not a footnote.

Taste Buds: A diaspora product, then a disciplined exit

Once you see these numbers, you see why a superstar would look at spices, restaurants, and branded food not as vanity projects, but as a direct extension of where his audience already lives.

In 2004, Mohanlal stepped into a space that many Indian celebrities now chase, but few dared to enter back then.

Packaged spices and condiments.

Mohanlal’s Taste Buds leaned heavily into the Gulf. One report noted that Taste Buds was believed to have done sales worth Rs 3 crore from the Gulf market alone in the first six months after its launch.

The spice market at the time in the Middle East alone was pegged at Rs 2,000 crore, with MTB holding 1% of the market share.

Mohanlal also started a chain of restaurants with the same name. Unfortunately, those did not do well.

In a Dubai interview, Mohanlal was unusually direct about the failure of the Taste Buds restaurant chain in the Middle East. “Taste Buds closed because of difficulties in managing it properly,” he said.

Then he did something even rarer in celebrity business. He exited or should I say, he consolidated his business enterprise.

In December 2007, just three years into Taste Buds, Mohanlal sold the spices and condiments brand, to Eastern Curry Powder, with Eastern owning majority stake.

The most telling detail is not the sale itself. It is what Eastern’s chairman said about the brand in the Gulf.

“Taste Buds is the second largest curry masala brand in the Middle East market. We will retain the brand name,” Navas Meeran told The Times of India at the time.

This is what disciplined entrepreneurship looks like. Build something, prove a demand. Sell to scale. Do not let ego keep you in a business where your edge is no longer an edge.

If you look at it that way, Taste Buds is not a failure story. It is a case study in knowing when to stop being the operator.

Aashirvad Cinemas and Maxlab: How Mohanlal started owning the pipe

If Taste Buds was Mohanlal trying to sit inside the diaspora grocery basket, Maxlab was him trying to sit inside the plumbing of the cinema itself.

Because the wealthiest people in film industries are rarely only actors. They are the ones who control distribution, exhibition, and infrastructure. They own the pipelines through which everyone else must flow.

Mohanlal met Antony Perumbavoor in 1986-87 on the sets of a movie he was filming; by this time, he had acted in almost 140 films.

Antony’s own biography describes how he began as Mohanlal’s chauffeur in 1987, and how during the filming of Pattanapravesham he joined as a temporary driver for a 22 day schedule before Mohanlal later pulled him back in and made it permanent.

By 1999, the trust and friendship that the two developed, turned into a joint venture, leading to the establishment of a film production company – Aashirvad Cinemas.

Aashirvad’s first production, Narasimham, is the moment the machine announces itself: released in 32 centres in Kerala, it ran for 200 days and grossed Rs 22 crore, becoming one of the early proof points that Malayalam cinema could create record economics when packaged right.

Since then, Aashirvad has produced over 30 films, effectively turning Mohanlal’s stardom into a catalogue that keeps earning long after opening weekend hysteria moves on.

Then comes the second lever. In 2009, Mohanlal, Antony, and industrialist K C Babu set up Maxlab Cinemas and Entertainments, a distribution and production company that regularly distributes Aashirvad titles.

This is where it becomes a juggernaut, because it is no longer only about making films, it is about moving films, pricing them, and widening them. And they do not stop at distribution.

Aashirvad’s own site says it now manages 27 screens across Kerala, meaning the network stretches from production to distribution to exhibition.

Lucifer as proof of the system

If you want one modern example of how this pipe prints money, look at the 2019 film Lucifer produced by Aashirvad and distributed by Maxlab: made with a reported ₹30 crore budget, a reported Rs 129 crore gross, and more than 160,000 admissions in the UAE in just three days.

In the business of films every layer you own throws off a different kind of cash: producer upside, distributor margin, exhibition revenue, and a long tail of rights control.

It also reduces risk. When one film underperforms, the pipe still earns because the pipe is fed by volume, not by one hero shot. That is how a superstar stops being merely rich and starts behaving like an institution.

The Quiet Assets: Post production and real estate

There is a particular kind of intelligence in the investments that sit where the audience never looks.

VismayasMax is exactly that kind of asset. Kerala’s first DTS studio, headquartered in Thiruvananthapuram with a branch in Kochi.

A superstar owning postproduction infrastructure is not a vanity flex. It is a quiet redistribution of power. When you own the finishing room, you own time. You own schedules. You own the last mile where films either come alive or get stuck in limbo.

In July 2014, management moved to UAE based Aries Group’s BizTV arm. Although the deal value was not disclosed, according to Indian Express, at the time, this acquisition had made the company the largest film and television studio in India.

Then there is the overseas concrete. The Gulf is not just his second audience; it is also the geography where his money chooses to sit closest to his people.

Public reporting has linked him to property in Dubai’s most symbolic addresses: an apartment in the Burj Khalifa, a villa in Arabian Ranches, and a luxury home in Downtown Dubai’s RP Heights.

The point is not the price tag. It is the map. He has parked real estate in the city that functions like Kerala’s offshore extension, where the diaspora lives, earns, and keeps one foot emotionally at home. In his portfolio, Dubai is not a postcard. It is a second base.

This is the deeper pattern. He invests at the same points where he is most exposed. In cinema, he reduces dependence on the mood of the market by owning the machinery that completes and distributes work.

In life, he reduces dependence on one country’s uncertainty by holding hard assets in the city that mirrors his diaspora economy.

Acting pays, yes. But these moves are not about payment. They are about permanence. That is the real upgrade from celebrity rich to investor rich.

Baby Memorial Hospital: The stake that turns celebrity rich into investor rich

The most investor coded piece of Mohanlal’s portfolio is also the one many barely register: healthcare.

In 2019, Economic Times reported that New York based investment film KKR & Co. planned to invest up to Rs 300 crore in Khozikode based Baby Memorial Hospital. The report mentions that Mohanlal held a significant minority stake in the hospital.

In July 2024, multiple reports said KKR would acquire around 70% stake in the hospital at a reported valuation of Rs 2,500 crore, roughly $300 million.

You do not need to guess Mohanlal’s exact percentage to make the point: if a hospital platform is being valued in the thousands of crores, a “significant” minority stake suddenly stops sounding like a celebrity hobby and starts reading like a serious wealth pillar.

The why also has a neat narrative bridge to his public life. Mohanlal’s ViswaSanthi Foundation, started in 2015, positions healthcare as a core mission area. It has publicly stated partnerships with Baby Memorial Hospital on healthcare initiatives like its “ReLiver” programme.

So, the story writes itself in two layers: the soft layer is purpose, health access, public good. The hard layer is equity in a healthcare network that institutional capital wants to scale.

Put together, it is the same Mohanlal pattern again: build trust first, then build ownership.

What remains after the performance

I return back to Vanaprastham, because the ending is the beginning.

The make up comes off. The role ends. The world returns to its hierarchy.

That film understands the brutality of conditional love. Mohanlal’s real life seems to respond to it with strategy.

He built a career that constantly reinvented itself, and a portfolio that does not require him to be the most loved man in the room every year.

He does not invest like a man trying to look clever. He invests like a man trying to avoid regret.

Food that travelled with the diaspora and then sold to a strategic buyer. Finance services built for retail participation and local trust.

A healthcare stake connected to an institution that drew KKR capital at a multibillion rupee valuation and then became a consolidation platform.

Cinema companies that treat distribution and rights as power, not afterthought.

This is not the story of an actor who got rich. That is common.

This is the story of a superstar who treated fame as a high-income job, then built a real balance sheet so the job would never be the whole life.

If Danny’s lesson was that quiet operators can outlast loud emperors, Mohanlal’s lesson is subtler and perhaps more useful for anyone who earns in volatile cycles.

Build buffers. Build optionality. Treat applause as temporary. Invest as if the makeup will come off one day.

Because it always does.

Ankit Gupta has spent almost two decades working with India Today, NDTV and Times Internet. He is a senior creative lead at Hook Media Network within the RP Sanjiv Goenka Group. He writes on the business of entertainment, fashion and lifestyle, bringing a producer mindset to reporting and analysis.