In 2018, a Mumbai woman named Nisha Patil left behind a will that reads like obsession set in legal ink. She had never met Sanjay Dutt in her life and yet, she left him all her property, worth about Rs 150 crore. Dutt learnt of it through the police, refused to claim it, and returned it to the family.

So, when people say movies and movie stars are like religion in India, they truly underestimate the hold cinema has over its fans. Their logic is irrational, but it is consistent: if a star gives his life to the public, the public gives him immortality.

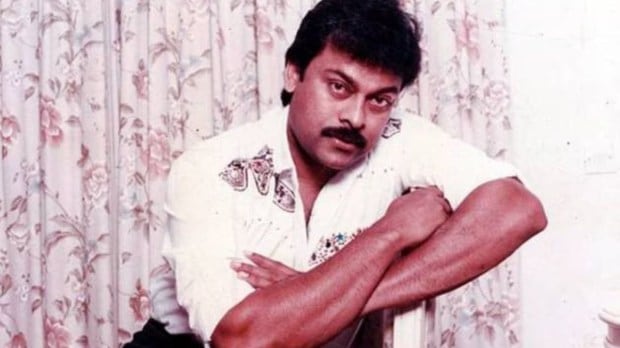

Chiranjeevi, at the height of that kind of worship, got poison.

It was 1988, an outdoor shoot around Chennai. He was nearing his 100th film. By this point in his career, he was not merely famous. He was a phenomenon. The kind of man for whom the word “Megastar” is not a compliment; it is a job description.

During a break between the takes, fans gathered close enough to breathe the same air as him. Someone stepped forward with a cake. A birthday, he said. It was presented like an offering, white cream already soft in the heat, carried with both hands like a ceremonial object that couldn’t be refused. This was a familiar script. The star cuts the cake, the crowd cheers, a quick photograph becomes proof of grace. Everyone gets what they came for, and the shoot moves on.

The man pushed a piece of cake toward Chiranjeevi’s mouth. He resisted, instinctively, in the scuffle, some of the cake got into his mouth. The rest dropped to the ground.

The crew noticed something odd about the fallen icing. A powdery texture that did not belong in the cake. Within minutes, his lips began to turn blue. That powder was poison.

He was rushed for treatment, survived and returned to work. This is not a story about one deranged fan with a cake. This is also a story about scale.

This is what mega stardom looks like when you strip the music away. When you are loved at that volume, your body, some people begin to believe, belongs to the public too. The same crowd that will worship you can also consume you.

When a star learns, viscerally, that fame is not just applause but also exposure, sometimes in the extreme, the smartest response is not to build higher walls. Walls are temporary.

The smarter response is to build wealth that does not require your body to be present at all.

Wealth that sits elsewhere, in ownership, in equity, in stakes inside the machine that runs even when the lights are off, even when the crowd has gone home, even when the star is no longer on set to cut the cake.

Chiranjeevi’s billionaire bet

Most stars respond to danger with walls, convoys, private entrances, and more people with earpieces. Those things help, sure, but they also keep you trapped inside the very life that makes you vulnerable. They still require you to show up. They still require your body to be the engine of your wealth.

The smarter response is to build money that does not need you at all. Money that earns while you are asleep, while you are off screen, while the crowd is cheering for someone younger. Money that sits in ownership, not performance.

In early 2006, Chiranjeevi quietly entered Maa Television Network as part of a new promoter group alongside Nagarjuna and Nimmagadda Prasad. The Economic Times reported in June 2006 that the trio was expected to pick up around 60 percent of Maa TV, valuing the enterprise at roughly ₹110 crore, with the group bringing in about ₹66 crore for that controlling stake.

What made the move especially telling was how deliberately low profile it was: the same report noted his involvement was being kept under wraps and would likely be revealed only when the channel was relaunched. In other words, this was not a star chasing publicity. It was a star buying distribution.

By 2015, regional television in India had already become the real habit economy, long before streaming arrived. South India, ran on appointment viewing: daily soaps that structured evenings, movie channels that owned weekends, music channels that stayed on in the background like a household member.

In that landscape, Telugu was not a niche. Mint described it as the second largest regional TV market by revenue, pegged at about Rs 1,800 crore annually, and Economic Times reported that Maa Tv controlled roughly 26 percent market share among Telugu channels while operating a bouquet of four channels across general entertainment, movies, and music.

So, when Star India bought the broadcast business of Maa Television Network in 2015, it wasn’t a surprise. What did surprise many was that the deal was widely reported in the Rs 2,000 crore to Rs 2,500 crore range. Chiranjeevi’s stake in Maa TV was at 20 percent. Do the blunt math and you get an implied Rs 400 to Rs 500 crore slice of value sitting quietly behind the megastar.

If Maa TV was the headline trade, iQuest was the wiring behind the wall. Corporate records show Chiranjeevi appointed as an additional director at iQuest Enterprises in September 2008, with other familiar names in the same promoter universe appearing across periods, including Nagarjuna and Ram Charan.

iQuest Enterprises was not a vanity company or a “celebrity side hustle.” It is a distribution company, a cable operator. And distribution is where Indian entertainment becomes a habit, not an event. Even by the Indian regulator’s own sizing, India’s television industry is a tens of thousands of crores machine, with subscription revenues forming the biggest block.

In 2020, the TV industry was pegged at Rs 68,500 crore, and subscription revenue alone at Rs 43,400 crore. That is the scale of river you are standing next to when you buy not just into television but also distribution.

That instinct for buying the pipeline instead of only starring in the show did not appear overnight. It came from a boy who entered Telugu cinema without a family studio, without a safety net, and learned early that survival depended on understanding systems, not just scenes.

Before Chiru, there was Varaprasad

Contrary to popular opinion Telugu cinema is not a boutique cultural industry. It is one of India’s biggest production engines, and by sheer output it routinely sits at the top of the pile. In 2024, Telugu releases were the highest among Indian languages at 323 films, part of 1,823 theatrical releases across languages that year, as reported from FICCI EY data.

When people picture Telugu cinema, they picture Hyderabad as a permanent address. Big studios. Glossy sets. An ecosystem that looks like a city within a city. But when Chiranjeevi arrived, the industry still carried the smell of Madras.

For decades, Telugu language cinema had been built in Chennai, with studios, technicians, processing labs, and the whole production pipeline rooted there. The shift to Hyderabad began in the 1970s and only truly completed by the 1990s, which meant the late 1970s were a strange in between time, an industry with one foot in its old home and one foot searching for a new one.

Into that moving landscape walked a boy who had not inherited access to any of it. Chiranjeevi was born in Mogalthur, West Godavari, on 22 August 1955, to a father who worked as a constable. A constable’s household did not produce film stars, it produced routine, transfers, and a kind of early alertness.

New towns meant new schools, new classmates, new social codes to read quickly. It was not glamour. It was training, the kind you only recognise later when you see how fast a man can adapt to unfamiliar rooms.

One detail from those years has stayed with him because it felt like a rehearsal for being watched. In the early 1970s, he was in the NCC and participated in the Republic Day Parade in New Delhi – a teenager from coastal Andhra marching in a national spectacle where every step had to be exact. It taught him something simple and useful: how to hold your body steady while thousands of eyes measure you.

He did the sensible thing first. He studied commerce at Sri Y N College in Narsapuram. Then he did the less sensible thing, the kind that makes a middle class family go quiet for a moment before it adjusts.

In 1976, he moved to Chennai and joined the Madras Film Institute. In that decision you can already see the instinct that later defined him, a willingness to leave the familiar, to enter the factory, to learn the system from inside.

His first break arrived in a way the industry often allows outsiders in, not through destiny but through scheduling.

He was not the first choice for his debut film, Punadhirallu. Another actor was approached first, dates did not work out, and the part slid to the young man then known as Shiva Shankara Varaprasad, now fondly known as “Chiru.”

The ruffian who ruled the market

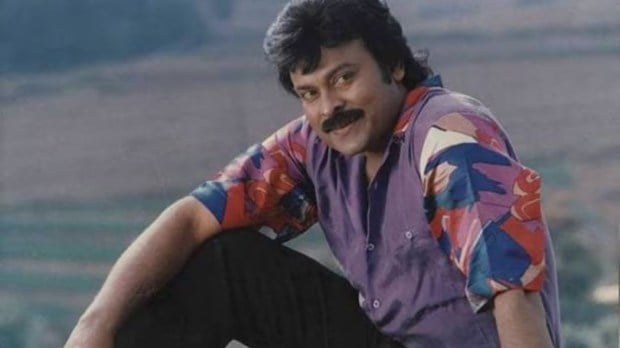

In the first stretch of Chiranjeevi’s career, he was the angry young ruffian with too much kinetic energy, the kind of character who could walk into a frame and make the temperature rise.

He debuted in 1978 and, for a while, the work came fastest in supporting parts, antihero turns, and outright antagonist roles, there is a useful phrase that follows him around in criticism for a reason: screen rowdy.

S V Srinivas’s book frames his transformation across decades as a movement from “screen rowdy” to “reformer”, which is a neat way of saying the persona started with roughness before it learnt respectability.

But the real shift, the one that turned him from popular actor into market event, arrived in 1983 with Khaidi. Indian Express has described it as his first major commercial breakthrough and the moment he gained stardom.

Khaidi did something more specific than just making him “famous.” It locked his energy into a format Telugu cinema could replicate and sell at scale: rage with righteousness, action with grievance, a rebel who did not look like a visitor in the world of fists and dust. The film is widely cited as having been made on about Rs 25 lakh and grossing around Rs 6 crore. A relatively small film had created a disproportionately large star.

The years that followed read like an industrial rollout. He got upgraded. He became the mass hero who could dance, fight, make comedy land, and still carry a moral axis that satisfied family audiences.

By the early 1990s, the certainty had become bankable enough to rewrite actor compensation nationally. A key milestone is his reported Rs 1.25 crore remuneration for Aapadbandhavudu in 1992, framed as breaking the one crore barrier and making him the highest paid actor in India at that point.

In early 1990s India, when a “big” Hindi film budget could still sit in the single digit crores, crossing one crore as an acting remuneration was not just a personal milestone, it effectively reset the top end of star pricing.

Around the same time, the cultural headline for that market power became explicit: Hindustan Times notes that The Week put him on its cover in 1992 with the headline “Bigger than Bachchan.”

Chiranjeevi became the kind of star whose films did not merely entertain, they moved the financial needle of an entire ecosystem, and once you can command that sort of money for showing up on set, you start thinking of making your life and investments bigger than cinema itself.

The stadium economy

On a Kerala Blasters night, you can see why Indian sports ownership seduces film stars. The stands turn into a single yellow organism, drums and flags and chants rolling in waves, an atmosphere that looks less like entertainment and more like ritual. The audience does not arrive once for opening weekend and leave. It keeps showing up.

Chiranjeevi’s move into this world came through the Indian Super League era, when Indian football tried to build an IPL style ecosystem with prime time broadcast, celebrity owner heat, and city based franchises.

In 2016, a consortium including Chiranjeevi and Nagarjuna joined Sachin Tendulkar as co-owners of Kerala Blasters.

When Tendulkar later exited, New Indian Express reported that the buyers committed about ₹120 crore over ten years, and it also noted the less glamorous truth beneath the fireworks: the club had racked up losses close to ₹100 crore in four years.

Those numbers are the context most celebrity sports stories avoid, but they are exactly what makes this one legible.

This was not a quick profit play. This was patient capital in a league where cost structures were heavy. Economic Times has described ISL clubs spending roughly ₹30 crore to ₹40 crore and paying an annual franchise fee in the ₹12 crore to Rs 15 crore range.

You do not write that cheque if you are looking for tidy returns next quarter. You write it only if you are looking possibility of long term appreciation once the league matures and media rights and sponsorship pools deepen.

The other tell is structure. This was not a scarf and a photo. Corporate listings show Chiranjeevi as a director of Magnum Sports Private Limited, the vehicle associated with the consortium’s sports holdings. And Magnum Sports is also listed as the owner of the Pro Kabaddi franchise Tamil Thalaivas.

That expansion matters because it shows a platform instinct, not a one-off purchase. Kabaddi, unlike Indian football, has already put valuation markers into public discourse. Economic Times quoted a Mashal Sports official in 2023 saying Pro-Kabaddi League franchises would be valued at over Rs 100 crore each.

Badminton is the quieter tell in Chiranjeevi’s sports portfolio because it sits away from the stadium noise and closer to clean, sponsor friendly league economics. Corporate listings show him as a director of Matrix Badminton Teamworks Private Limited.

Trade reporting around the Premier Badminton League then makes the ownership link clear: the consortium associated with him and Nagarjuna offloaded its PBL franchise to Matrix Badminton Teamworks, and the team was rebranded as the Bengaluru Raptors. In other words, this was not a celebrity cameo. It was a board level position in the company that owns the team.

The economics here are not fantasy, they are structured league money: each franchise operates with a defined player purse, with Brand Equity reporting PBL expecting about ₹50 crore in revenue in 2018 and building extra rights for franchises through city leagues and academies.

Magica Sports Ventures Private Limited is the next layer of the same story, another sports holding vehicle where filings list him as a director, suggesting a deliberate habit of packaging sports assets inside companies rather than leaving them as informal partnerships.

Put simply, football gave him the stadium roar, kabaddi gave him the regional league machine, and badminton gave him the cleanest long game: a structured sports asset tied to a sport with prestige, corporate appetite, and a calendar that keeps paying attention rent even when there is no film release.

The Konidela production machine

Once you have written cheques for a club through lean seasons, you stop romanticising “passion projects.” You start asking the grown up question: where is the asset that I can control end to end, where the upside is not dependent on a league table or a referee’s whistle? For him, that answer was not outside entertainment. It was deeper inside it.

Anjana Productions was the Konidela family’s first serious attempt to convert Chiranjeevi from talent into ownership.

Launched in 1988 with his brother Nagendra Babu and named after their mother, it was a home banner designed to control projects, rights, and leverage rather than only chase acting fees.

Their first big statement, Rudraveena, directed by the legendary filmmaker K Balchander and Chiranjeevi starred alongside Gemini Ganesan and Shobana. The film set the tone for the risk profile: it was mounted on a reported budget of about Rs 80 lakh and later described as a critical success but a commercial failure, with a reported ₹60 lakh loss for the producer. The film earned itself the Nargis Dutt National Integration Award along with two more at the National Film Awards that year.

That is not “failure,” it is the real economics of production: the banner became a place where the family could back prestige swings and learn, painfully, that the upside of ownership comes with the downside of underwriting.

The next evolution is how that ownership instinct scales into a modern studio structure through Konidela Production Company, set up by Chiranjeevi’s son Ram Charan, and was used to mount Chiranjeevi’s return as a commercial event.

Their first major release together, Khaidi No. 150, carried the kind of numbers that explain why families build studios in the first place: it is widely reported at a ₹50 crore budget and ₹164 crore gross, and Forbes reported that it collected a distributor share of Rs 90.35 crore in just 12 days.

You can argue about exact final tallies across regions, but the business point is clean: production ownership turns a star’s comeback from a personal career moment into a balance sheet event, where the family sits closer to the rights, the distribution, and the profit pool instead of only being paid for performance.

What the Chiranjeevi playbook tells us

In the Chiranjeevi story, the cleverness is not that he earned a lot. Lots of stars do. The cleverness is that he kept migrating to forms of power that outlive the mood of a crowd.

Television gave him habit.

Sport gave him repeat footfall and a franchise shaped like a long bet.

Production gave him rights, library, and the ability to turn a comeback into a balance sheet event.

Even the lanes we have only glanced at, politics, philanthropy, endorsements, keep echoing the same instinct: do not just be loved, become institutional.

Politics was his most public stress test, the moment fandom tried to become governance. It did not rewrite the state the way his films rewrote the market, but it clarified a truth most stars learn too late: applause is emotional capital, and emotional capital does not automatically become organisation.

Philanthropy is where he did the opposite conversion, taking that same crowd energy and routing it into a system that runs without a camera, blood, eyes, logistics, repeatable service. Endorsements, meanwhile, sit in the background like cashflow, not the story, but the funding layer that keeps the machine well fed.

So the real verdict is not that Chiranjeevi became rich. It is that he learnt to stop living entirely inside the crowd’s mood. In a country that treats cinema like religion, he did not just accept worship. He quietly studied its economics, its risks, its expiry dates, and then built systems that survive them.

Today his net worth is pegged at about Rs 1,650 crore, making him a billionaire in the plainest rupee sense of the word. But the more interesting point is what that number is built on: not just the memory of hit films, but a portfolio of pipes, franchises, rights, and institutions, the kind of assets that keep working even when the crowd has moved on to its next god.

If you want to keep reading, here are some more money trail stories from Bollywood Billionaires, each about a different kind of wealth and a different kind of survival.

Sonam Kapoor is the modern version of inherited advantage done intelligently, where the real play is not “acting fees” but brand equity, fashion capital, and the kind of cultural positioning that turns visibility into a long runway of deals.

Mohanlal is the quiet math of longevity, where superstardom becomes infrastructure, the Gulf becomes both audience and asset geography, and the smartest moves are the ones that do not need loud announcements.

Danny Denzongpa is the blueprint for disciplined wealth, a man who built a fortune by doing fewer things, doing them better, and treating his career like a risk manual instead of a romance.

And Abhishek Bachchan is what it looks like when a famous surname stops being a safety net and becomes a business platform, with investments and brand plays that reveal a different kind of ambition than the one the gossip pages like to sell.

Ankit Gupta has spent almost two decades working with India Today, NDTV and Times Internet. He is a senior creative lead at Hook Media Network within the RP Sanjiv Goenka Group. He writes on the business of entertainment, fashion and lifestyle, bringing a producer mindset to reporting and analysis.