By Srinath Sridharan

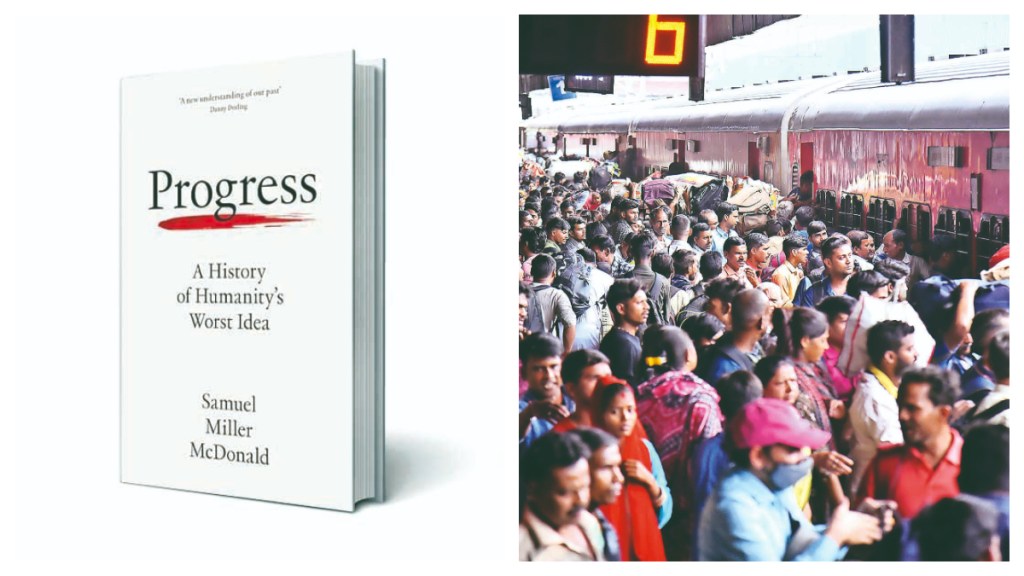

Few ideas have seduced humanity quite like progress. From the Enlightenment’s candle-lit salons to Silicon Valley’s glowing screens, we have told ourselves one great story: that the world is getting better—faster, fairer, freer. In Progress: A History of Humanity’s Worst Idea, Samuel Miller McDonald asks whether this cherished notion is not in fact a myth—one that blinds us to the ruin in our rear-view mirror. What if progress, the idea we celebrate as civilisation’s triumph, is actually the story of its undoing?

McDonald’s argument is sweeping and unsettling. He suggests that progress—that glittering word which politicians, scientists and billionaires utter as mantra is not an achievement but a disguise: a moral-alibi for exploitation, a story invented to justify power and soothe conscience. “We have mistaken speed for direction, and change for improvement,” he writes, setting the tone for a work that challenges not only history, but the way we think.

The book begins before civilisation’s dawn—in what McDonald calls “the time before progress”, when human life was still embedded in the natural world. “When we ceased to live with nature and began to live off it,” he observes, “civilisation was born — and so was hierarchy.” It is this shift, from coexistence to extraction, that he traces across five millennia.

The book section Before Progress traces the first rupture, when humans stopped living with nature and began living off it, turning coexistence into control. In Heaven, McDonald journeys through ancient myth and faith, showing how divine order became a tool to justify hierarchy and conquest. By Nation, progress has been reborn as Enlightenment— cloaked in liberalism, industrial ambition, and the language of reason. In System, the story darkens. Progress becomes machinery: perfected by fascism, sanctified by modernism, and globalised by neoliberalism. Every ideology, he argues, shares the same fever for endless growth. After Progress closes with a fragile hope to rebuild civilisation on reciprocity, ecological balance, and moral restraint.

McDonald organises all of history around what he calls ‘parasitism’— humanity’s evolving modes of living off one another and off the planet. The earliest empires, he argues, practised contiguous parasitism: their exploitation was local and territorial, tied to nearby resources. This was the age of city-states, kingdoms and temples, where progress wore the robes of religion and myth. Between 1400 and 1900, as empires took to the seas, parasitism turned disparate—maritime, colonial, global in reach.

Progress now spoke the language of reason and rationality. And by the 20th century, the pattern became networked—driven by fossil fuels, financial flows and ideology. The modern world, McDonald argues, is parasitic in the most abstract sense: it harnesses not only nature’s energy, but human energy— through waged labour, digital dependency, and the endless compulsion to produce and consume.

He pairs this with an equally striking distinction between “concrete energy capture”— the direct use of resources from the environment—and “abstract energy capture”, the exploitation of human or social energy in the service of others. From the slaves who built pyramids to the coders training algorithms, McDonald sees a continuous story of domination masked as development.

His point is not historical nostalgia but moral continuity: that our current economic order is simply the latest chapter in an ancient pattern. Today’s economists, he notes, speak of exponential growth as if it could continue forever on a finite planet. “We have been sprinting ever faster down a corridor,” McDonald warns, “without knowing where it ends.”

McDonald’s critique lands hardest when he turns to the present. The world’s richest societies now resemble, by some measures, the inequalities of their most primitive ancestors. The United States— modernity’s self-proclaimed frontier— has a Gini coefficient on par with slave-owning Ancient Rome. Maternal mortality rates for American millennials are three times higher than for their parents’ generation. Global life expectancy, once the poster-child of progress, is falling.

These illustrate the deeper paradox of our times: the more we chase progress, the poorer our quality of life becomes. So what explains our complacency? McDonald’s answer is blunt: false consciousness. Even our rebellions, he notes, tend to seek minor reform rather than genuine reimagining.

His moral anger is clear: “The dream of endless improvement,” he writes, “is the ideology of those who already live well enough.” For the rest of humanity, progress has too often meant displacement, degradation, or dependency. The myth of advancement, he suggests, has allowed us to normalise ecological devastation and moral exhaustion.

McDonald’s scope is vast—part history, part philosophy, part ecological treatise. Drawing on anthropology, geography, and systems theory, he dissects the ideological scaffolding that has propped up progress for centuries. If humanity is to thrive, he argues, we must dismantle and reimagine what progress means. The idea itself need not die—it must be reborn in equilibrium with the regenerative capacity of the Earth.

This is not an easy book to read. It is dense, slow, and layered with references that span from Mesopotamia to Marx. At times, it feels almost academic in its precision, its paragraphs packed with data, theory, and cross-disciplinary insight.

McDonald’s background as a geographer and left-environmental activist gives the book its moral force, but his analysis resists orthodoxy. He is diagnosing a civilisational psychosis. His tone can feel sermon-like, but beneath the rhetoric lies reason. He marshals rigorous research— including insights from his Oxford Dphil —to expose the inconsistencies between our ideals and our outcomes.

McDonald offers what he calls a “hopeful vision.” He imagines a civilisation built not on extraction but on regeneration— one that measures success by restoration, not expansion. The book is aspirational, but it gestures toward a moral horizon. “To live well,” he writes, “is to stop mistaking more for better.” It is perhaps the simplest sentence in the book, and also its most radical.

Progress: A History of Humanity’s Worst Idea is demanding—a blend of scholarship and moral provocation. It asks not just whether the modern world is sustainable, but whether our very idea of advancement is. For readers interested in questioning assumptions about development, inequality, ecology, and history’s supposed arc, this is a vital, but a deeper read.

Yes, it is cumbersome, slow, and packed with detail. McDonald’s writing is passionate, sometimes polemical, but purposeful. “If the myth of progress built our world,” he concludes, “perhaps only its unmaking can save it.”