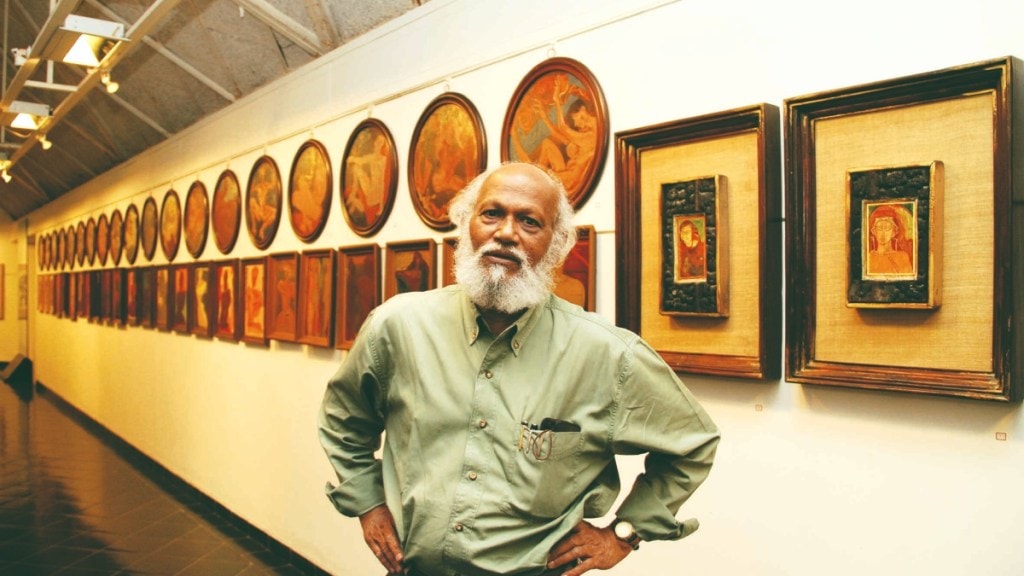

Born in Baripada in the erstwhile princely state of Mayurbhanj (now Mayurbhanj district in Odisha) in 1941, Jatin Das was prompted by his family to study science. Instead, at the age of 17 years, he headed for the JJ School of Art in the then Bombay to become an artist. He graduated from art school in 1962 and moved to Delhi six years later to make the national capital his home. His first mural in Bombay in 1965 was an egg tempera fresco, a technique rarely used then. In 2001, he would go on to paint a 476-sq-ft mural (The Journey of India: Mohenjo-Daro to Mahatma Gandhi) at the old Parliament building. In his nearly six decades of career, the figurative artist has worked on different mediums as a painter, sculptor, muralist and printmaker. On the occasion of a retrospective of his works at the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA), Delhi (Jatin Das: A Retrospective: 1963-2023, November 26–January 7), the artist talks to Faizal Khan about his long career, influences, challenges and what he thinks of digital art. Edited excerpts:

What were the main aspects of selection of works for the retrospective? How did you go about the preparation from personal and private collections?

There is never enough time to sieve through 60 years of work and so it was not easy at all. I began to take out old works that I had not seen for half a century.

I was surprised to see how the figuration in my works has changed and evolved over time. There was no time or money to get works from various collectors in different parts of the country. So, I showed what was in my studio. I still have more than double in the studio that I could not exhibit because of lack of space. A couple were taken from the NGMA collection and from a collector in Ahmedabad who offered to send. For curation, even though the artist knows his own works the best, some distancing is also important. For the first time, my children, (filmmaker) Nandita Das and Siddhartha Das, curated the show. In a way, it was good, as it allowed them to know my work better.

The 1,000-plus portraits you have painted describe a collaborative relationship you had with fellow artists. How did this relationship influence you in your early career?

I did portraits right from my JJ School of Art days, mostly of friends and people I know except for the commissioned ones. A portrait is not a documentation and likeness to the person is only a part of it. It is more about the artist’s attempt to create depth in the essence of the person. Only then does a portrait become a work of art. I like to do portraits when I have some connection to the person. Ideally, I like to spend a fair amount of time with them, to get to know them better. But sometimes, I also like to do quick portraits—of a shopkeeper, a waiter, a househelp, or anyone that catches my eye. In 1959, while I was still a student, I had a studio at Bhulabhai Memorial Institute on Warden Road, (then) Bombay. The rent for my studio was only a rupee a day. A year later, stalwarts like Madhav Satwalekar, VS Gaitonde and MF Husain had their studios there. Pandit Ravi Shankar took classes and so did BK Iyengar, the great yoga teacher. Jatin (actor Rajesh Khanna) and Harihar Jariwala (actor Sanjeev Kumar) rehearsed their plays. Gieve Patel and Nissim Ezekiel would sit and read their poetry. Yamini Krishnamurthy, Sonal Mansingh and Madhavi Mudgal’s first performances in Bombay were held at the Bhulabhai Memorial Institute. Those early friendships and exposures would have surely impacted me and my work.

How do you look back at your six-decades-long journey as an artist in terms of the progress of modern and contemporary Indian art? What have been the major decisions and challenges?

Mine has been a long journey with many struggles and many amazing experiences. Right from the exciting early years at the JJ School of Art and vibrant days in Bombay to the glorious days in the ’70s in Delhi with artists and galleries that truly cared about art, to travelling to different artist camps and shows all around the world. From the early ’90s, I got into collecting arts and craft objects. The collection became so large that I decided to set up the JD Centre of Art. Lot of my money, time and effort went into it. Finally, the building is now ready and we hope to open the centre next year. I often say, I am a painter who wants to be an artist. And to be an artist, you need two or three lives. One life is not enough. But now there is a sea change in the art world. People talk about the art market and art business, and those who come to see your works are called clients! Artists of my generation never used such words. Though I have successfully insulated myself from commodification of my work. Art has been eroded by the market. I find it laughable that art buyers treat works of art as alternative currency. I have never cared about the noise of the art world. I paint the canvas and then disengage.

You arrived in Delhi in 1968 and made the city your home instead of staying back in Mumbai where many of your contemporaries were. What made you opt for Delhi?

Pupul Jaykar, the great cultural revivalist of handloom and crafts, invited me to Delhi to become an art consultant for the Handicraft and Handloom Export Corporation. At that time, Kumar Art Gallery in Delhi was one of the most respected and known galleries in the country. They began to show my work. While shifting to Delhi in 1968, I brought along with me five large wooden boxes containing my sketches. When I opened them, they had been eaten up by white ants. I had to burn them all with a lot of pain. I managed to retrieve a few, including those of Ustad Bade Gulam Ali Khan and Lata Mangeshkar.

Your new work, Manhole Cleaners, part of the Labour Exodus series, reflects a sense of urgency to address social concerns. How do you view the role of an artist in relation to a much-changed and division-filled society today?

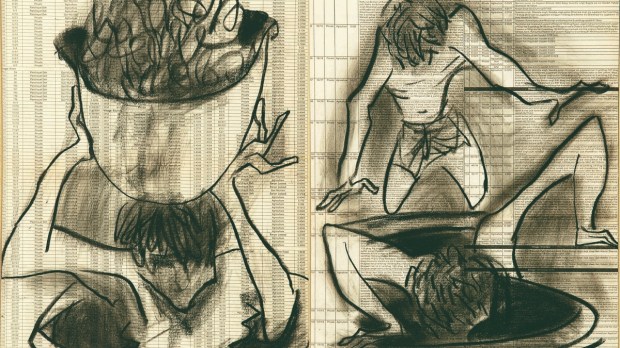

They are two different series. Like everyone else, I was stuck at home during the Covid-19 lockdown. What I missed the most was going to my studio, where I work from morning to late evening. I spent most of my time cooking and cleaning. But I was restless at home. I had 200-odd acid-free papers, some ink pots and lots of brushes. So I began painting. What I saw in the newspapers and on television came pouring out spontaneously. And that is how Labourer Exodus series was born. During the lockdown, the migrant workers who build our homes and cities had to go back to their villages. There was no work in the city, no earnings. Thousands of them walked barefoot, some went on cycles and others atop buses, under the scorching sun, without food and water. They went with their belongings tucked under their arms or on their heads. Men and women carried their children on their shoulders, in baskets, in their tired arms, walking quietly through days and nights, non-stop. This is a special series, a response to those troubled times. My inspiration for my work has always come from the working classes. Those who make roads, lay bricks, paint high-rise buildings, the beldars, the thelawallahs, manhole cleaners, rag pickers, domestic and construction workers—all those who toil non-stop. In India, we live in different centuries simultaneously. With all the so-called development, there is still extreme poverty. People are still cleaning manholes in 2020. They have to enter filthy dark sewers to clean them, risking their lives and exposing themselves to diseases. Thousands drive past them in their fancy cars, without even looking at them. It is shameful. I decided to do a series on manhole cleaners. And that too, using basic charcoal on newspaper, mounted on simple cardboard.

What about digital art? What is your opinion on digitally created artworks in relation to labour and creativity?

I do not even touch the computer, so I don’t understand the digital world at all. In my view an artwork needs to only be seen in person, in its real dimension and at the distance it demands. It is an experiential thing, not something that can be seen on screen. But these days, who is really looking at the work itself? I understand that there are advantages to the digital world. I too was forced to exhibit my Labour Exodus series online during Covid. I know of even known artists who do digital drawings, then use them like a stencil on canvas and fill colours. It is really sad. But I feel we will come back to authentic, creative and honest work when this cycle is over.

What is the future of art in the backdrop of technological changes like Artificial Intelligence?

Sorry, I don’t understand technological things like artificial intelligence. Anything artificial for me is not what I relate to. I am sure it has its advantages, but I believe in human interaction and human connections.

What is your advice to younger people just beginning their career as artists?

The so-called modern education system has created many divisions and has limited the imagination of a child. Today, a dancer is not exposed to sculpture or painting and the architecture student studies western architectures but has not seen our diverse monuments and temples in different parts of India. So, various forms of arts are disjointed and completely divorced from life. A teacher in school draws a mango instead of taking the student to a mangrove to smell, draw, and then eat the mango. To find your true self in art, one has to unlearn everything. Wipe it out. Then do manodharma. Sadly, we are taught to focus on the goal. But what is important is the journey. I urge young people to experience and explore their surroundings first. Learn from nature and folk and traditional arts which are the most important influences for an artist.

Faizal Khan is a freelancer