By Krishnamurthy Subramanian

In the late 1970s, China’s supreme leader Deng Xiaoping envisioned ‘Four Modernizations’ as a strategic plan for China’s economic development. Agriculture, industry, defence, and science and technology represented the four pillars that laid the foundation for China’s rapid economic growth and turned it into the powerhouse it is today. Japan’s post-War resurrection stemmed from its economic vision, which hinged on four pillars: industrial policy, education, infrastructure and export-oriented growth. This strategic framework propelled Japan into becoming an economic juggernaut, underscoring the transformative power of a well-structured economic vision. Similarly, Germany’s famed ‘social market economy’ relied on a four-pillar approach comprising a balance between a competitive market economy, a strong welfare state, labour market policies, and active fiscal policies. This comprehensive strategy laid the groundwork for Germany’s economic prowess.

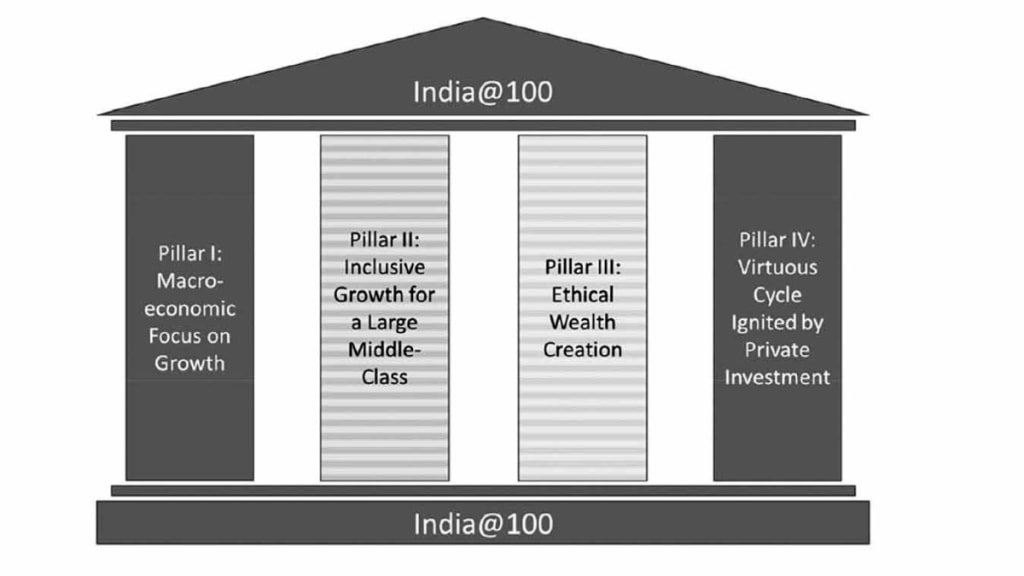

To realize PM Narendra Modi’s vision of Atmanirbhar Bharat, I propose an economic strategy grounded on four essential pillars. These pillars, which represent the essential foundations for prosperous and equitable progress, are shown in Figure 1.

Economic Development for All

The first two pillars specify objectives at the macroeconomic and microeconomic levels: to complement a laser-like focus on economic growth at the macroeconomic level with socio-economic inclusion at the microeconomic level. This will ensure that the benefits of economic growth are equitably shared among citizens. The macroeconomic focus on growth will uplift the lives of millions directly as the high rates of economic growth in India since 1991 and in China since the 1970s have demonstrably achieved. Simultaneously, high rates of growth will help to generate the resources that can be utilized for welfare programmes to double down on the economic development of the poor and vulnerable.

The microeconomic focus on socio-economic inclusion will help to not only reduce inequality, but also enhance aggregate demand in the economy. This pillar recognizes the importance of inclusivity in economic development. It aims to reduce income inequality and provide equal opportunities for all citizens, especially marginalized groups. By promoting social welfare programmes and initiatives, India is working towards creating a more equitable society and ensuring that all citizens have access to necessities and opportunities to thrive.

The explicit separation of macroeconomic and microeconomic objectives enables comparative advantage, and thereby enhances efficiency. Specifically, rather than hobbling macroeconomic policies with reducing inequality and thereby jeopardising growth prospects, the separation enables optimization of macroeconomic policies for growth on the one hand, and microeconomic policies for socio-economic inclusion on the other. As the Tinbergen Rule, advocated by the recipient of the first Nobel Prize in Economics, Jan Tinbergen, postulates, a one-to-one mapping between a policy tool and a policy objective fosters economic efficiency.

The third pillar—focus on ethical wealth creation—reflects this shift in the thinking of new India, which views wealth and wealth creation, acquired ethically, as a boon and not a bane. This is a significant break from the muddled narratives of the past that viewed profit as a dirty word. This change towards embracing wealth creation is a durable one because our policy now recognizes that ethical wealth creation has been part of India’s DNA for millennia. The idea of ethical wealth creation as a noble human pursuit is rooted in India’s old and rich tradition ranging from Kautilya’s Arthashastra to Thiruvalluvar’s Thirukural. The primacy of wealth creation in India’s DNA is reinforced by the fact that the common person writes ‘शुभ लाभ’ (shubh-labh; generate profit by doing good) at the altar in his home. Given the demonstrated economic benefits that India reaped from pursuing wealth creation by enabling economic freedom—both historically and post the 1991 economic reforms—India’s conviction towards embracing wealth creation by enabling economic freedom is solid.

To enable the process of wealth creation, the government is not only enabling and empowering the private sector, but is also assuming the responsibility of investing in physical and digital infrastructure. The policy of enabling the private sector in areas where there are no market failures allows two fundamental drivers of economic policy—incentives and information—to work for the economy rather than against it. As the private sector usually under-provides on public goods or indulges in monopoly pricing when it does create them, the government has taken on the task of creating both the soft and hard infrastructure as public goods so that access to the same is universal. Thus, to return back to India’s DNA of treating ethical wealth creation as a boon, the government is now focussing on doing what it should do and relinquishing activities that are better done by the private sector.

The Nehruvian socialist era saw the State playing the twin roles of a mass employer of citizens and a mass producer of goods. To drive India@100 to peak economic heights, India must boldly jettison anachronistic ideologies about the large and pervasive role of the State as the provider of employment and producer of goods. In many spheres of the economy, controls still proliferate thereby inhibiting both growth and citizens’ welfare. Reforms to dismantle them are being undertaken to not only enhance growth but also enable citizens’ ease of living. India needs to take these reforms to their logical conclusion.

From a provider of employment through its public sector enterprises (PSEs), the State needs to transform fully into a catalyst for employment. Given the uncertain global environment, demand-side shocks remain inevitable. Most government-run businesses often struggle to maintain the agility and dynamism required to thrive in such an environment. Moreover, data, analytics and technology are increasingly assuming significance as the fourth factor of production and are ushering in the fourth Industrial Revolution. State-owned enterprises lack the nimbleness in business practices or the adaptability in technology to keep pace with the changes in this factor of production. Further, lifelong job security, which derived from the State’s role as the primary employer, is an anachronism in a fast-evolving economy where the churn among businesses, let alone employees, is at a historical high. The State can no longer play the role of mass employer. Instead, the State will act as a catalyser of employment so that firms find the talent they need and workers find the rewarding employment they seek.

Similarly, the State will no longer play the role of mass producer in India. Although exceptions exist, the average public sector entity is less profitable, grows slower, and is less productive than the average private sector entity. To achieve the goal of becoming a global economic powerhouse by 2047, India must grow at 8 per cent annually in real terms or 13 per cent in nominal terms. India cannot grow at 13 per cent when India’s PSEs grow at barely 5 per cent on average. It is simple arithmetic! A country cannot grow at 13 per cent unless its businesses grow at that rate. Each PSE that lags its private counterparts in innovation and growth is depressing the growth of the economy. India’s policy has, therefore, recognized that the only way to unleash growth is for the government to open up the closed sectors. Except for some strategically critical sectors, where the State’s role cannot be ceded to the private sector, the government needs to get out of business to enable better business. There is no dearth of private players in India, nor is there any dearth of finance or technology, to prevent the private sector from taking on the State’s role in managing businesses.

Virtuous Cycle for Economic Development

The fourth pillar, a ‘virtuous cycle’ driven by private investment, adds substance to the macroeconomic model for high growth. This virtuous cycle has at its centre public expenditure on physical and digital infrastructure to ‘crowd in’ private investment as well as supply-side reforms that will help remove various frictions on the supply side of the economy, thereby accelerating private investment.

The virtuous cycle originating from private investment is crucial for sustained economic growth in India. Investment leads to productivity gains and creation of jobs, both of which increase disposable income in the economy and thereby foster consumption. Thus, in the first-round effects embedded in the virtuous cycle, private investment is most crucial for enhancing consumption. In the second-round effects embedded in the virtuous cycle, anticipated increases in consumption spur further investment by the private sector. The virtuous cycle delivers explosive growth as consumption and investment feed each other symbiotically.

India @100: Envisioning Tomorrow’s Economic Powerhouse

Krishnamurthy Subramanian

Rupa Publications

Pp 520, Rs 995