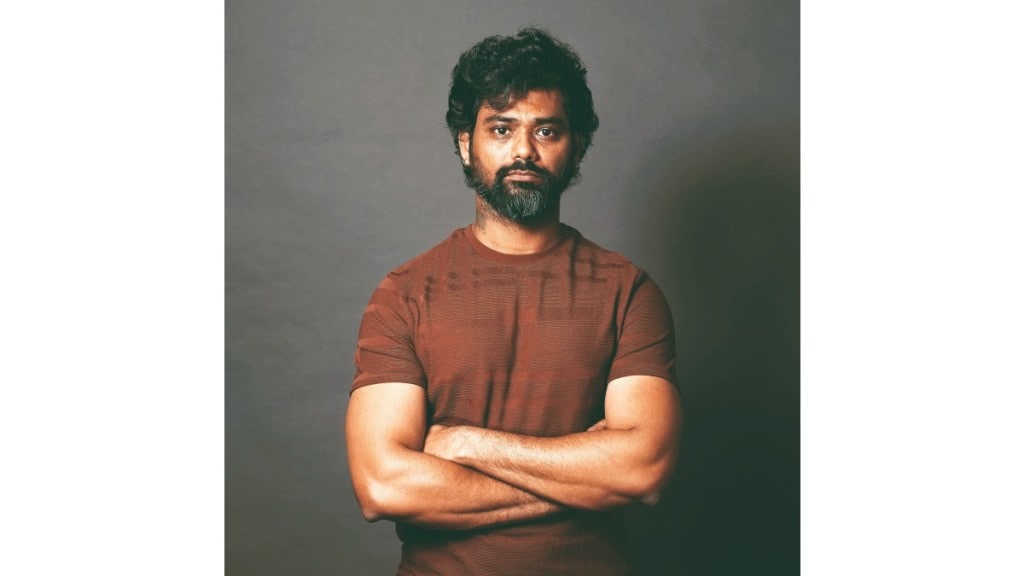

Rohan Parashuram Kanawade, writer and director of Sabar Bonda, which won the Grand Jury Prize in the ‘World Cinema: Dramatic’ category at the Sundance Film Festival and was the first Marathi-language feature to be screened at the prestigious event, speaks about

his film, making independent cinema, and more. Edited excerpts:

How did you get into filmmaking?

I grew up in a slum in Mumbai. My father was a driver. But he would regularly take us to watch films. That’s where my love for cinema started and it was with gadgets actually. I remember being barely four years old and asking my father if the cinema hall was a big TV. He explained to me what a projector was; and even though I did not understand, I was hooked and excited. For me, going to the cinema was hoping that I would get a chance to go into the projection room and see how it works.

I saw a 16-mm projector for the first time when my school organised a screening of Shyamchi Aai. As a child, I also made a slide projector with a bulb, an empty shoe box, and some film strips. I would organise film shows for my friends on it. This love found another avenue when I watched Jurassic Park and got obsessed with the concept of surround sound. In school, I would also write stories, which my teachers encouraged and pushed me to keep at it.

Even while I was working as an interior designer in 2007, I tried making a short film with my friends and colleagues on a Nokia phone with a 1.5-megapixel camera, and Windows Movie Maker. We never finished it, but the process was so exciting that I decided I wanted to make more movies.

Sabar Bonda is a very warm and tender film, and one that is full of hope. What inspired you to tell this story?

The idea for this film came to me in 2016. My father had passed away, and my mother and I went back to our ancestral village for the mourning period. It was a claustrophobic experience for me. Ever since I had passed class 10th, my relatives had started talking about my marriage. Now that I was 30, and had suddenly become the head of my family, the questions became more intrusive.

That was when I started wondering about how if I had a friend in the village, I could sneak out and escape this pressure. That thought stayed with me for a very long time. I decided to change the experience and make it into a tender story. I started writing the story in 2020 with no expectations. At the time, all that writing the story meant was remembering my father, reimagining our conversations, and that made me happy.

My father was a very progressive man. When I came out to him, he accepted me, and said if I know myself, that’s all that matters. His support was what gave me the encouragement and space to be a filmmaker. Even though he had poured all his life savings into getting me an interior designing diploma, when he recognised my passion for making films, he told me I should switch careers if that made me happy. This came from a man who had left his job as a driver, started his own business, seen it tank, and then gone into depression—that was the kind of man he was, who loved and supported me unconditionally.

I had already made four short films that had gone to film festivals and been recognised internationally before I started writing Sabar Bonda in 2020. It was his absence that made me write this story, as if he was still supporting me from far away.

Your film is as much about mourning the loss of a loved one, as it is about finding a shared sense of love with another person. What is it like to tell a story that’s extremely local at its core, but the themes are universal—love, loss, self-discovery, class and gender prejudices?

I’ve always felt that most queer films made in India have impressions of Western queer films. When I watched those films, I could not relate to their lives. With Sabar Bonda, I wanted to show real and lived experiences. I wanted to make a film that was local, where I could show our roots. And I wanted to make a queer film that feels Indian.

But even though my premise was that of grief and mourning, I did not want to make a sad film. I wanted the film to give the audience a warm hug, and show that cinema dealing with important issues can be gentle and tender at heart too.

While independent cinema made by Indian filmmakers has been appreciated globally, is finding producers for such films still a challenge? Three out of six producers on Sabar Bonda are from the UK and Canada.

Finding producers is difficult for sure. We faced a lot of rejections for Sabar Bonda and it took us a long time to finally make the film. People did not believe in us, our story, or even the fact that we could ever make this film. We were told that this is not the popular way of making films—without any songs, and on a queer subject. “Who will watch such a film?” was a common question.

I was lucky that Neeraj Churi (of Lotus Visual Productions), who had produced my short film U for Usha in 2019, wanted to collaborate on this project again. In fact, towards the end of our project, one of the financiers backed out and Churi had to mortgage his house for Sabar Bonda. A lot of our queer friends also funded the film and helped us. At the post-production level, Sidharth Meer (Bridge PostWorks) and Naren Chandavarkar (Moonweave Films) came on board too.

But a lot of independent films go through labs and markets because that’s an essential way to secure funding—either meeting potential investors or through grants.

Your film went through a lot of labs and markets too—the Venice Biennale College Cinema 2022-23, the NFDC Marathi Film Camp, Film London Production Finance Market, Film Bazaar Co-Production Market, to name a few.

I’m not a trained filmmaker and I never went to film school. Through labs, I was hoping to get the mentorship and guidance I required from professionals to hone my craft.

I also wanted the script to get some visibility and meet international sales agents to ensure that the film is on their radar from the very beginning, because I always intended to take my film international. It also helps give other people confidence in your film when your script is selected at prestigious festivals.

What next will we be seeing from you?

Right now, Sabar Bonda’s journey has just started. We’ve received invitations from many international film festivals. But I want to take a break after having worked on this film for five years. I do have some ideas, but my thoughts and stories have a long gestation period. There is a story that I’ve been thinking about since 2018 but I haven’t had the chance to start writing yet.