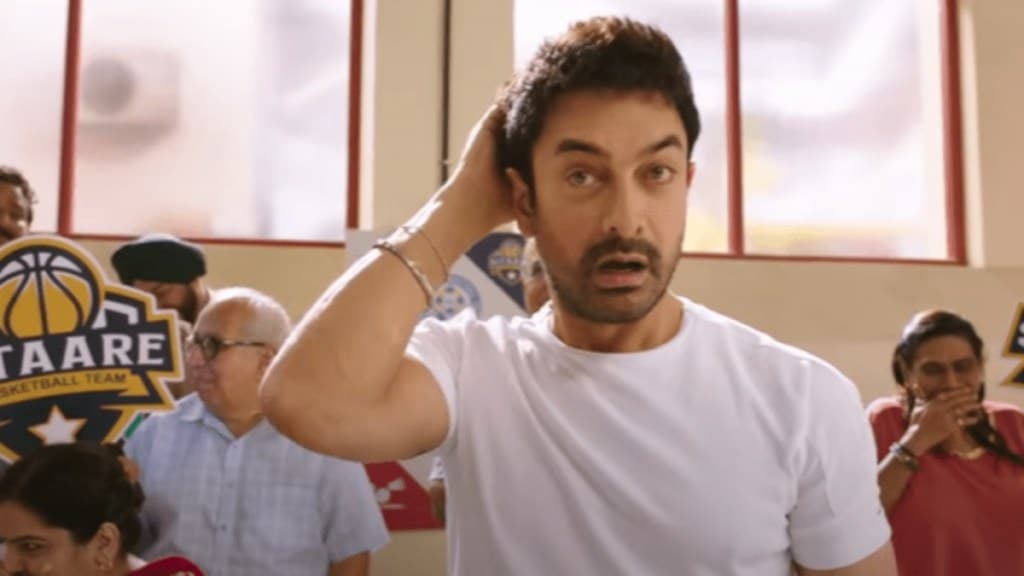

Aamir Khan’s decision to go for YouTube’s pay-per-view service for his new movie Sitaare Zameen Par is an audacious attempt at challenging the norms of digital distribution in Bollywood. If successful, filmmakers will reclaim the spotlight from OTT platforms & broadcasters, explains Urvi Malvania

Change in modes of film distribution post-Covid

Earlier, films were distributed on two major platforms — theatrical release followed by a satellite release on television channels. Since the Covid-19 pandemic, a digital distribution layer has been added where streaming rights are sold to OTT platforms. Meanwhile, the rising cost of going to the movies (upwards of Rs 2000 for a family of four) has led to cinegoers preferring to view a film on OTT. The “window” between a theatrical release and OTT availability has also shrunk from months to mere weeks. This shift allows films to recoup investments faster and access a more diverse audience. Streaming platforms have also redefined “success”; beyond box office numbers, engagement metrics and content longevity now play a crucial role. The once-dominant satellite TV rights market has also been disrupted, with many films opting for OTT-first deals. Streaming has not only democratised access to content but also changed how and where films earn, turning OTT platforms into both primary distributors and essential financiers of Indian cinema.

How monetisation on digital platforms works

Most Indian films are monetised on digital platforms through subscription video on demand (SVOD) deals, where streaming services like Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, and Disney+ Hotstar acquire exclusive digital rights for a fixed fee, paid upfront. Networks such as Zee and Disney/Viacom18 which have an OTT presence also bundle digital and satellite rights in a single deal to maximise value. Another avenue is ad-supported video on demand (AVOD) which generates income through revenue share on ads rather than subscriptions. The third model is a pay-per-view model like YouTube TVOD (transactional video on demand) where one can rent the title on a platform for one-time viewing. The revenue is shared between the platform and producer.

Benefits of a YouTube release

A YouTube release, like Aamir Khan‘s Sitaare Zameen Par, could be a disruptive move since it gives the producers a long-term revenue stream with a global audience reach. In addition to this, the model could have a positive impact on the film’s theatrical run as consumers may be more inclined to pay for the movie hall experience than the YouTube pay per view experience. Films available through traditional OTT streaming deals often see public inertia to watch it in the theatres since these would be available on an OTT platform after 8-10 weeks anyway. This is especially true for films that do not have a high special effects element and watching them at home would not take away from the overall experience of the film. The TVOD model also democratises content distribution, since a filmmaker does not need anyone to broker OTT deals.

Trade-offs in this model

The TVOD or pay-per-view model is a performance-driven revenue model. The upside is that producers need not restrict the film’s digital rights fee to a fixed amount. Also, the title can gain from the platform’s algorithm to get visibility among digital audiences.

On the flipside, selling a film’s digital rights to a streaming platform offers financial certainty as producers get a fixed amount upfront, regardless of how the film performs post-release. In case of the TVOD model, if the film does not get a good reception it does have an impact on the producer’s revenues. Additionally, while the risk of piracy across legitimate digital platforms could be comparable, the impact of piracy on the producer in case of the pay-per-view model is higher, since it directly affects income from content consumption on the legal platform.

What it means for film distribution

A shift towards models like YouTube TVOD could mark further democratisation of film distribution in India, moving power away from large OTT platforms and broadcasters toward creators and consumers. If Khan’s experiment succeeds, it could encourage other filmmakers and independent producers to explore direct-to-audience monetisation strategies. The move also points towards a discretionary approach by OTT platforms when acquiring content, which could indicate a more bottom-line first strategy given the rising technology and customer acquisition costs. Widespread adoption of TVOD hinges on a cultural shift in viewer behaviour since a majority of Indian consumers are habituated to “free” or subscription-based content. Getting them to pay for individual films will require strong brand pull, and appealing content. This in turn will force filmmakers to devise distribution strategies that do not rely heavily on one digital distribution stream, but explore a hybrid model to maximise returns, and minimise risk. The window between a theatrical release and release on other media platforms could also see some change, allowing producers and platforms to better monetise a title.