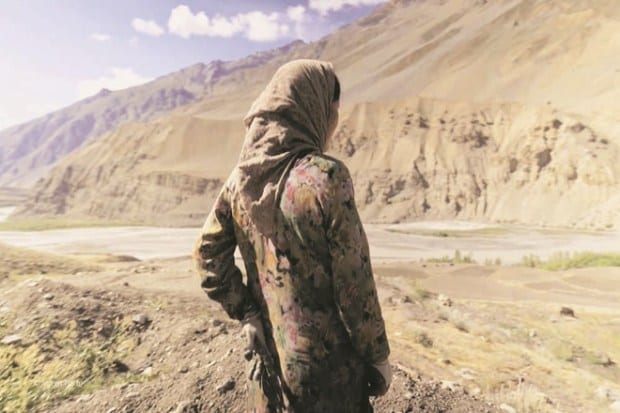

If you have no water, you have no settlement. It is a Ladakhi saying that is often heard in the Spiti Valley, a breathtaking Himalayan region lined by snow peaks where rain is sparse and life is a struggle. The valley’s farming community is proud of the shiny green peas they harvest, but since the plants need a lot of water the yield is limited to just once in a year. The dry weather is made harder by the receding glaciers that pack frozen water for the people, many of whom are now turning to prayers for more snowfall.

“Prayers are not going to bring more snow,” says Chilkat Tzamo, a Spiti Valley woman who works in her field every day tending to the shrinking green peas plants. Instead, Tzamo and her fellow farmers decided to take things into their own hands. Armed with the Rs 5.6 lakh they raised through crowdfunding on social media, the Spiti farmers installed a solar pump at the faraway Zing Gongma lake and laid a long winding pipe to bring water to their village. The snowfall hasn’t shown any promise since then, but water is today trickling down the taps in Spiti’s farms.

No Water, No Village, a 29-minute film on Tzamo and other farmers’ ingenious irrigation methods, is part of the seventh edition of Science Film Festival that is being simultaneously screened in southeast Asia, South Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Latin America from October 1 to December 20. Organised by the Goethe-Institute in partnership with the United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021-2030), the event has 150 films from 35 nations this year. Twenty-nine of them will be screened in India in hybrid format, free online (www.sciencefilmfestival.org ) and in-person events at schools and museums in 25 cities across the country.

“The Science Film Festival is a significant project of the Goethe-Institut, which has grown considerably since its first edition in 2005 to become the largest event of its kind,” says Marla Stukenberg, regional director for South Asia, Goethe-Institut. “The festival is a celebration of film as a medium to promote science literacy and raise awareness of contemporary scientific, technological, and environmental issues in accessible and entertaining ways,” she adds. According to Goethe-Institute, 30,000 people in India attended the festival last year. The audience worldwide in the same edition was one million.

No Water, No Village is joined in India by films like Jungle Babblers, the not so ‘Angry Birds’, Borshi: The Fish Hook, Sundarbans: Stuck Between a Cyclone and a Rising Sea, Saving the Himalayan Yak, Faces of Climate Resistance: Nurturing a Forest and Tiger Army. “Alongside catalysing meaningful engagement with this year’s theme of ecosystem restoration, our hope is that the festival might contribute to the education of future generations for a more sustainable planet,” says Stukenberg. The theme last year was Equal Opportunities in Science.

Jungle Babblers, the not so ‘Angry Birds’, part of the six-film Bioacoustics series, explores the wild orchestra of bird calls. “Jungle Babblers are misunderstood as ‘Angry Birds’ because of their noisy chatting,” says Megha Moorthy of Roundglass Sustain, a not-for-profit digitally documenting India’s biodiversity that has produced the film. The five-minute film made from archival material shows the fascinating behaviour of Jungle Babblers that are found near human habitats. Their bird calls include a contact call to fetch a fellow bird left behind, flight call to flee and even a lookout call to alert those foraging. Three of the Bioacoustics films are screened at the Science Film Festival, including in India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Singapore and Brazil.

Two short films from the 16-part Faces of Climate Resilience series, which captures the voices of people in some of India’s most climate-vulnerable regions, highlight how local communities are adapting to climate change through locally-developed solutions. One of the films, titled Uttarakhand’s Young Water Scientists, is set in Sud village near Nainital where local students allot themselves depleted springs to recharge them. In Nurturing a Forest, set in Maharashtra’s Ahmednagar, one of the most drought-prone districts in the country, villagers use ‘climate smart’ methods like burying earthen pots beside plants to aid moisture retention from drip irrigation to save water. “We want to communicate what we are discovering through our research,” says Milan George Jacob of Delhi-based Council on Energy, Environment and Water, which has produced the Faces of Climate Resilience series that has documented local climate adaptation practices in Kerala, Maharashtra, Odisha and Rajasthan, besides Uttarakhand.

The festival, which has received 1,700 entries from 102 countries this year, will be screened in Goethe-Institute in New Delhi, Chennai, Mumbai, Kolkata and Pune and partner-institutions like National Council for Science Museums and Kendriya Vidyalaya. Society for All Round Development, another festival partner in Delhi that promotes digital learning, will take select films to classrooms in government schools in the national capital and Haryana. Films produced in India will be screened in other countries during the festival while foreign films are part of the official selection in India.

Faizal Khan is a freelancer