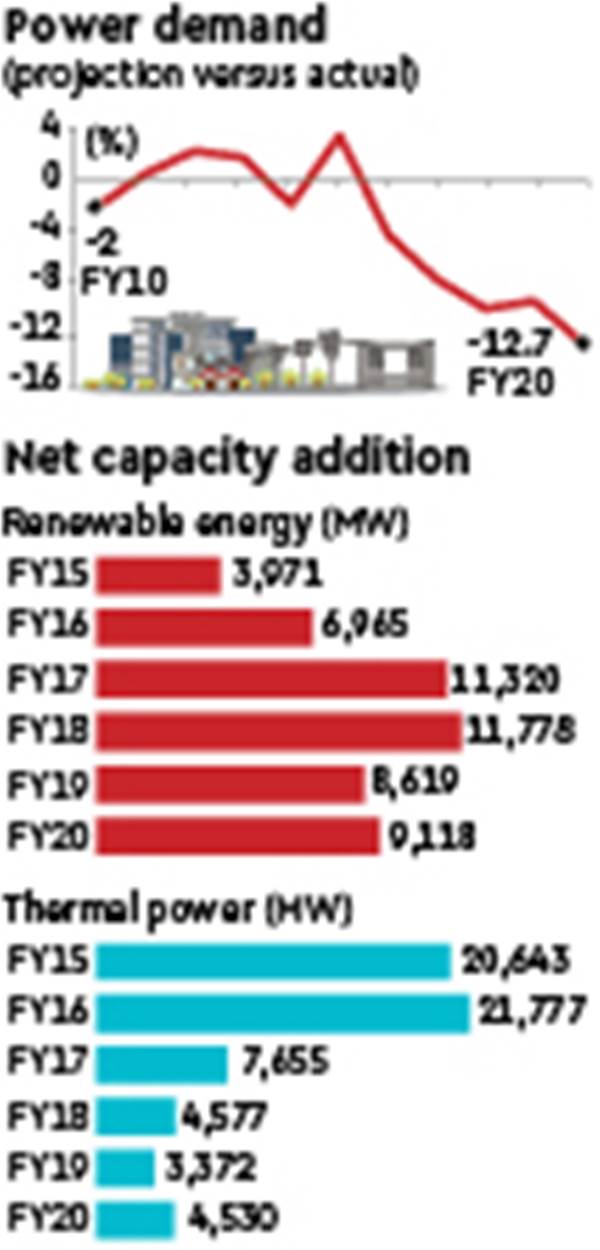

For the fifth year in a row, electricity demand in the country trudged below the projection made by the government in FY20. The gap between the forecasts and actual demand persisted, even after the Central Electricity Authority (CEA) apparently scaled down the former a bit, over these years.

With the lower-than-anticipated growth in demand leading to stoppage of many large power generation projects – several of them have turned into non-performing assets –, capacity addition too have slowed. While the pace of thermal capacity addition saw a sudden deceleration since FY16, the renewable energy segment partially offset this trend (see chart).

Actual power consumption, a close proxy of demand, was 13% less than estimated by the CEA for FY20. As pointed earlier by a high-level empowered committee, the lower-than-anticipated growth in electricity demand is one of the primary reasons behind the stress in the power sector, with the utilisation level (PLF) of thermal units falling from 79% FY07 to 56% in FY20.

“Electric power survey carried out by the CEA uses the partial end-use method and has been missing out on accuracy, over-estimating the demand,” Debasish Mishra, leader, energy resources and industrials at Deloitte in India, said. “(Insufficient) quality of data received from states could be the reason for this,” Mishra added. The Union power ministry’s agencies tend to struggle to reconcile data received from state-run power distribution companies (discoms) with the information collected from elsewhere.

A senior government official told FE that that state governments do not follow uniform formulae and definitions of key parameters, and manual data management leads to errors and delays. Inadequate governance, accountability and transparency at discoms and lack of large data management skills have also been attributed to inferior data quality. A recent incident of projections going off the mark was also witnessed during the nine-minute lights-off event on April 5, when demand fell by 31,089 MW against the projection of 12,879 MW.

Projections of lofty demand had triggered a surge in commissioning of power plants resulting in a surplus-supply scenario. During FY12-17, a cumulative generation capacity of 99,209 MW was added against a target of 88,537 MW, outpacing the growth in demand and resulting in a declining trend of PLFs. Of course, the overall pace of adding thermal capacities have slowed down in the recent years. According to data reviewed by FE, thermal capacity addition on a net basis — the difference between the plants commissioned and retired — was only 4,530 MW in FY20.

“The new project starts from conventional sources (coal, gas, etc) have significantly declined over last 3-4 years as India has focused primarily on renewable energy for incremental additions,” Abhishek Tyagi, vice-president, Moody’s Investors Service, said. Out of the 23,730 MW of private thermal power plants currently under construction, only projects with 1,825 MW have announced the commissioning date, while others are listed as “uncertain”, according to a reply recently tabled in Parliament by the government.

However, with the country’s per capita electricity consumption still lower than the world average — this even compares poorly with other Southeast Asian peers. Tyagi believes that “electricity demand should increase as more reliable supply of electricity is made available to households and as the per-capita income of India rises”. Echoing similar sentiments, Kameswara Rao, leader, PwC India, said: “The progress of electrification from farms to kitchens to cars is building up demand. The available spare generation capacity is able to accommodate this incremental for now, and there is a growing view that new generation capacity has to be planned soon to meet the likely higher growth in demand in the future.”