The Bhopal gas tragedy

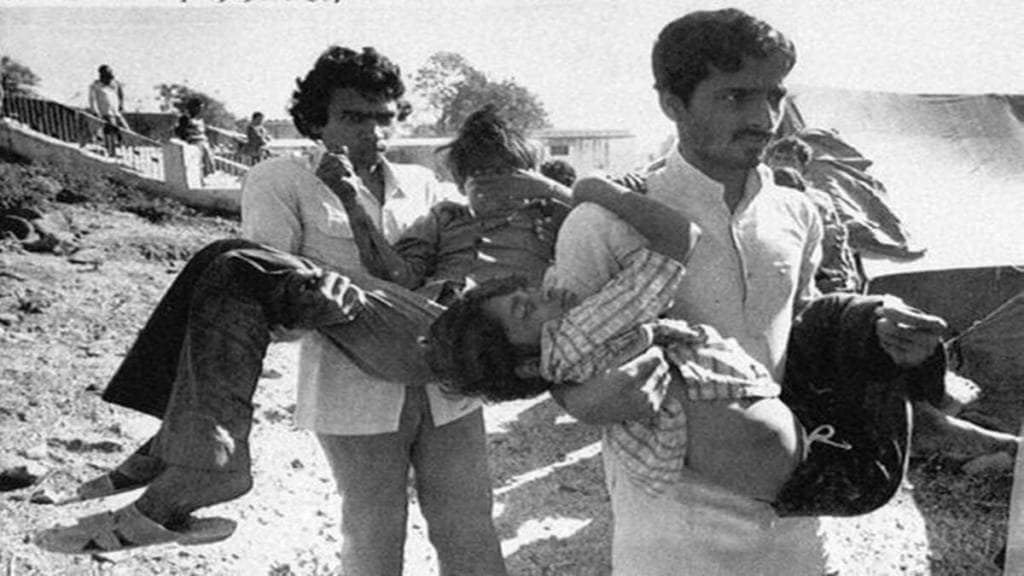

On the night of December 2-3, 1984, methyl isocyanate, a highly toxic gas, leaked out of a pesticide plant on the outskirts of Bhopal. Within a short span of time, thousands died from the gas’s effects, while tens of thousands suffered immediate injuries because of inhalation and exposure. Even today, the effects of the disaster lingers, with hundreds of thousands suffering long-term health effects. The reproductive health of several thousands of women in the city has been affected, with many who were exposed to the gas bearing children with congenital diseases.

The plant was owned by Union Carbide India Limited, a subsidiary of US-based Union Carbide (UC), that was taken over by the Dow Chemical Company, one of the largest chemical producers in the world, in 2001.

The settlement, and why the Centre wants it relooked

The Centre assumed all powers to represent and act in place of the victims on claims, through the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster (Processing of Claims) Act, 1985.

The Centre and UC arrived at an out-of-court agreement in February 1989, under which UC paid a total compensation of $470 million. The Supreme Court upheld the compensation amount in a May 1989 judgment and a 1991 order. In December 2010 — a few months after the SC dismissed the CBI’s curative petition to enhance the criminal liability of the accused — the Centre filed a curative petition seeking additional compensation, of more than 10X the 1989-deal amount. It says that the deal undercounted the affected; against the 3,000 deaths and 70,000 injury cases considered by the 1989 deal, the actual number of deaths is 5,295 and the number of injury cases is 5,27,984.

What SC has said

The Centre, in October 2022, had said it “cannot abandon the victims”, when it informed the SC that it will press on with the curative petition. The SC, which began hearing the curative petition on January 10, asked the Centre that even if it was right that “settlement was not the best”, could the matter be reopened.

The SC said the settlement had been arrived at by the two parties and had been approved by the court, and the Centre needed to “understand to what extent curative jurisdiction can be invoked”. It told the attorney general that the Centre, as a welfare state, must dip into its own pocket first to give relief to the affected. One of the judges in the Constitution Bench hearing the matter even said populism can’t be the basis for judicial review. The Times of India reports that the court warned of “wider ramifications” of reopening the settlement, especially as foreign companies look to invest in India.

The possible ramifications of reopening the settlement on India’s investment attractiveness

The Supreme Court’s warning on the ramifications of reopening for investment could be construed as foraying into the policy domain. But there are some indications that a reopening could have a bearing on India’s image as an investment destination because of perceived uncertainty in factors affecting the economic landscape.

Dow Chemicals, the company that now owns Union Carbide, maintains “it has no connection to the incident and does not belong in any legal proceeding involving Bhopal.” Yet, it has said of the 2010 petition that the government’s “ill-advised action puts at peril the image of India as a nation committed to promoting and adhering to accepted legal principles and the rule of law, with the inevitable result that confidence in investing in India will be undermined.”

While India has improved its performance on economic policy uncertainty in the index brought out by the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis—this had fallen from 153 in 2012 to 81 at the end of 2022—it ranked a very poor 163rd on enforceability of contracts in the now discontinued Ease of Doing Business Index of the World Bank. A business enabling environment would call for honouring even a bad but mutually agreed to deal.