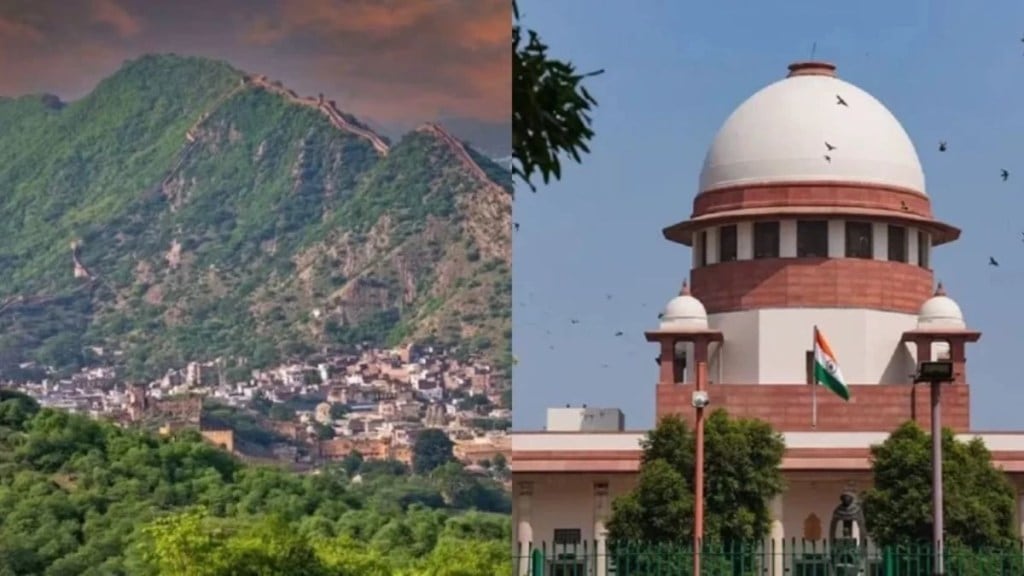

On Monday, the Supreme Court stayed its order issued just last month that had accepted the government’s 100-metre height definition for the Aravalli hills. Banasree Purkayastha explains why its assent had raised concerns about proliferation of mining activity in the already degraded mountain range

What has the SC said now?

A three member Supreme Court bench led by Chief Justice of India Surya Kant on Monday stayed its own November 20th order that accepted a 100-metre height definition for the Aravalli Hills, and decided to form a high-powered expert committee with domain experts to resolve all critical ambiguities. The decision to put on hold its earlier order comes after protests from environmentalists and political parties that the order could open the door to large-scale massive mining in the ecologically sensitive Aravalli mountain range.

“It seems prima facie that both the committee’s report and the judgement of this court have omitted to expressly clarify certain critical issues,” the bench said. “An analysis of whether sustainable mining or regulated mining within the newly demarcated Aravalli area, notwithstanding the regulated oversight, would result in any adverse ecological consequences… that aspect can be examined.”

It also issued notice to the Centre and the four states of Rajasthan, Gujarat, Delhi and Haryana across which the Aravalli range lies, seeking their response to its suo motu case on the issue. The next date of hearing is on January 21, 2026.

What had the previous order said?

The November 20th order had accepted a uniform definition of the Aravalli hills and ranges recommended by a committee of the ministry of environment, forest and climate change (MoEF&CC).

“Any landform located in the Aravalli districts, having an elevation of 100 metres or more from the local relief, shall be termed as Aravalli Hills… The entire landform lying within the area enclosed by such lowest contour, whether actual or extended notionally, together with the Hill, its supporting slopes and associated landforms irrespective of their gradient, shall be deemed to constitute part of the Aravalli Hills,” the committee had said. It defined Aravalli Range as a collection of two or more such hills within 500 metres of each other. The court had directed the ministry to prepare a landscape-wide management plan for sustainable mining based on this.

Why that order caused an uproar

Environment protection groups and opposition parties said that the 100-metre height definition could open up 90% of the Aravallis to mining and construction activities, especially in regions affected by rapid urbanisation. Leaving out the lower hillocks and ridges, which are integral to the Aravalli ecosystem, would also impact groundwater recharge and ecological continuity. “We are asking for this Supreme Court order to be recalled.

There is nothing called sustainable mining in a critical mountain ecosystem like the Aravallis. You cannot define an entire range for mining, that is completely unacceptable,” Neelam Ahluwalia, a member of the non-government organisation Aravalli Virasat Jan Abhiyaan had told ANI.

Congress leader Jairam Ramesh had written to Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav warning that the decision could break up the mountain system and weaken its natural and geographical unity.

What the govt said in its defence

The government had said it was wrong to assume that all landforms under 100 metres would henceforth be open to mining. While areas within the Aravalli hills or ranges are excluded from new mining leases, existing ones can continue if they follow sustainable mining norms, it said.

Last week, it clarified that the Supreme Court had directed that no new mining leases be granted until the Mining Plan for Sustainable Management is finalised by the Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education. It added that the blanket ban on mining would continue for core “inviolate” areas —protected forests, eco-sensitive zones, and wetlands — except for certain critical, strategic, and atomic minerals allowed by law.

Environment minister Bhupender Yadav said only 0.19% of the 1.44 lakh sq km Aravalli range could potentially be mined, and only after detailed studies and official approval. “The rest of the entire Aravalli is preserved and protected,” he had posted on X.

Why the Aravallis need to be protected

One of the world’s oldest mountain ranges, the Aravallis form a natural barrier against the expansion of the Thar desert in northwestern and northern India. The mountain range is a climate shield and water regulator for Rajasthan, Haryana, Delhi and Gujarat as it recharges aquifers, anchors soil and slows down dust storms. Environmentalists rue that prolonged urban expansion and mining activities have already sliced the continuous ecological belt into fragmented pieces.

A recent study by researchers from the Central University of Rajasthan suggests that by 2059, 16,360.8 sq km of forest that translates into about 21.6% of the Aravalli’s forest area, will be converted directly into settlements if current encroachment trends continue unabated. There have been decades of disputes and varying interpretations across states on what constitutes the Aravalli landscape, and what kind of human activity could be allowed there.