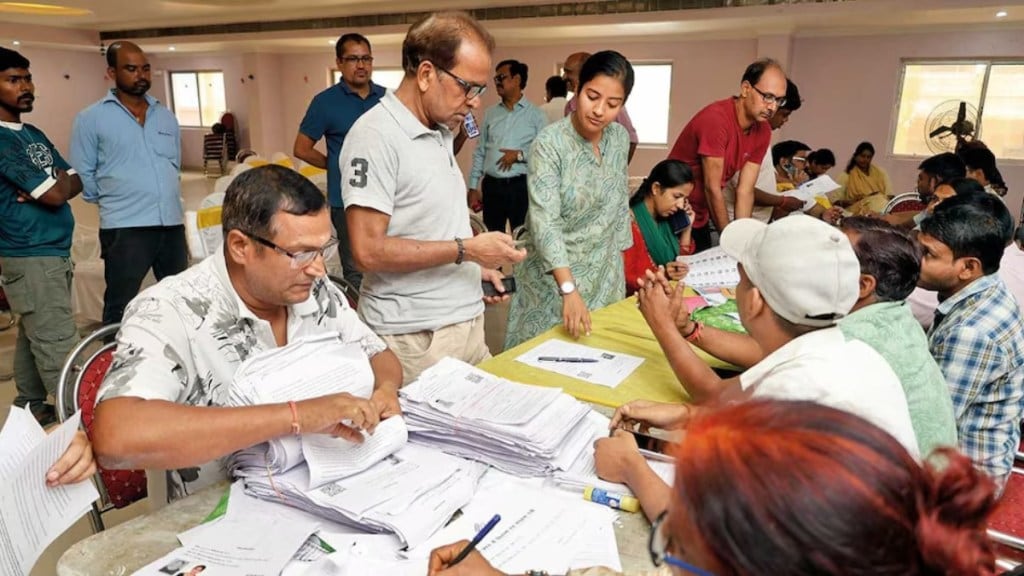

Bihar Election 2025: Considering the upcoming Bihar Elections, the Election Commission of India launched a Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of the state voter list. For the first time, voters were asked to show one of the 11 specific documents to prove their eligibility to vote. This unusual move was criticised by many and challenged in the Supreme Court, as it appeared similar to a citizenship test. But three months later, when the revision ended on Tuesday, the process looked very different. It had changed because of Supreme Court directions and feedback from officials working on the ground.

Initially, Aadhaar, ration cards, and even the EC’s own voter ID card (EPIC) were not accepted, though EPIC had been used in the last SIR in 2003. Only those whose names were on the 2003 electoral rolls were exempted from showing extra documents.

Court intervention and changes

Under the June 24 order, anyone not listed in the 2003 voter rolls, which was estimated to be about 2.93 crore people, had to show at least one of 11 documents to prove they were eligible to vote. These included things like government-issued ID cards, pension orders, certificates from banks, post offices, LIC or PSUs issued before July 1, 1987, birth certificates, passports, school or college certificates, permanent residence certificates, forest rights papers, caste certificates, entries in the National Register of Citizens, family registers, or land/house allotment papers issued by the government.

The rule was however quickly challenged in the Supreme Court. The EC defended it, saying Aadhaar could not be taken as proof of citizenship and pointing out that many fake ration cards were in circulation. The Court, however, asked the EC to make the rules easier and thus finally ordered that Aadhaar can be allowed as the ’12th document’.

Meanwhile, many officials in the field reported that people, especially in villages, were struggling to arrange the required documents.

Linking voters to the 2003 rolls

After getting the Court’s feedback, the EC later shifted its approach. Instead of asking everyone for documents, officials were told to trace voters back to the 2003 list directly or through family connections. By the end of the process, about 77% of Bihar’s voters were linked to the 2003 rolls, out of which 52% matched directly, and another 25% were identified as children or relatives of those listed in 2003.

For the rest, officials used state records like family registers (vanshavali), the Mahadalit Vikas Register, and even the Bihar caste survey to confirm voter eligibility. Booth-level officers, who initially faced confusion, were eventually instructed to focus on inclusion rather than rejection.

The final numbers

The revision ended with 68.6 lakh names deleted, mostly due to deaths, migration, or duplicate entries, and 21.5 lakh new voters added. Bihar’s final electoral roll now stands at 7.42 crore voters.