Every election in Bihar brings with it a new dynamic with the same parties, mostly the similar faces and the usual issues – development, liquor ban, women empowerment, poverty and education among others. The journey of Bihar is something that all the political parties narrate, but with their own convenience. Hence the narrative – jungle raj vs sushashan.

The ruling BJP-led NDA alliance under CM Nitish Kumar boasts about their sushashan (rule of law), comparing it with the ‘jungle raj’ of Lalu Yadav and his wife Rabri Devi. But is this really the case? Has Bihar, a state that lived under decades of lawlessness, is now enjoying sushasan? We will take you to a journey of Bihar from the Lalu-Rabri era to ‘sushashan kumar’ CM Nitish Kumar with hard facts

Bihar’s biggest evil – Law and Order

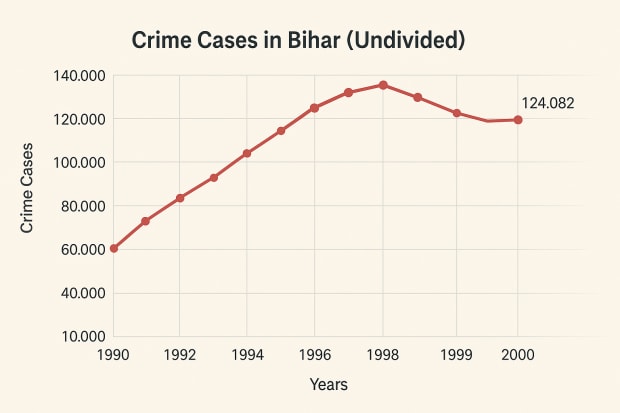

One thing that Bihar has been struggling to deal with for decades is the state’s law and order – it’s the biggest fodder NDA has used to attack Lalu Yadav-Rabri Devi’s reign. Years between 1990 to 2005 have been infamously termed jungle raaj, when the RJD under Lalu Yadav and his wife Rabri Devi ruled Bihar, the state witnessed an average 1.23 lakh cognizable crimes annually during the early 1990s, peaking in 1992, as per official National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) records.

But Crime figures for Bihar, especially from 1990 to 1995, were in fact lower when compared to other major Indian states like Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Uttar Pradesh. The crime started to deteriorate from 2000 onwards, when Jharkhand was segregated from Bihar. State’s share of crimes against women in 2000 also dropped to 4.7% of the national total, well below several other states. It was when Rabri Devi was the chief minister of Bihar and in coalition with RJD-Congress-CPI-CPI(M) government.

Apart from the concerns over the overall crime rate, several high-profile crime cases cemented the state’s image as lawless. Among the most shocking incidents was the lynching of Dalit IAS officer G. Krishnaiyyah in 1994, which highlighted the vulnerability of even senior officials to mob violence with political backing. Criminal cases against RJD leaders such as Mohammad Taslimuddin, a close aide of Lalu, further reinforced the perception of a political-criminal nexus.

The Shilpi–Gautam rape and murder case of 1999 became a national scandal, with allegations of gang rape and the involvement of Sadhu Yadav, Lalu’s brother-in-law. Despite police and CBI probes, the deaths were controversially declared a double suicide, a finding disputed by medical reports, and the case became a symbol of political interference derailing justice.

In 2002, at the wedding of Lalu’s daughter Rohini Acharya, RJD supporters allegedly looted automobile showrooms and drove off with brand-new cars, underscoring the climate of impunity. The reign of fear under Mohammad Shahabuddin, RJD’s Siwan strongman, added to the grim picture, with his record of kidnappings, murders, and extortion becoming emblematic of the so-called ‘jungle raj.’

However, time and again, Lalu Yadav has denied the political parties’ charge of ‘jungle raj’, calling his regime “was not jungle raj as is projected by political rivals”, rather, he claimed, his government led “rule of the poor”.

He even accused the NDA of bringing “real jungle raj” to Bihar, while stressing on increasing number of crimes under Nitish’ rule.

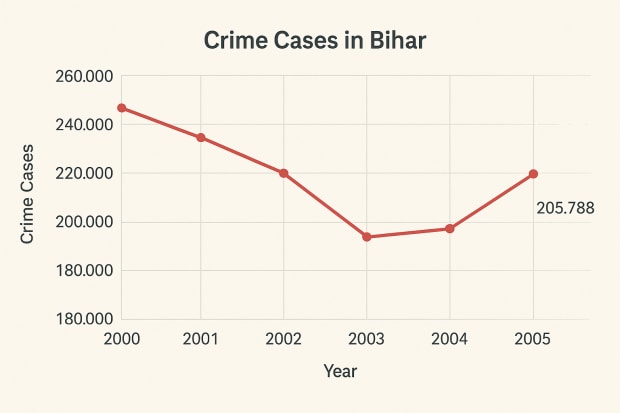

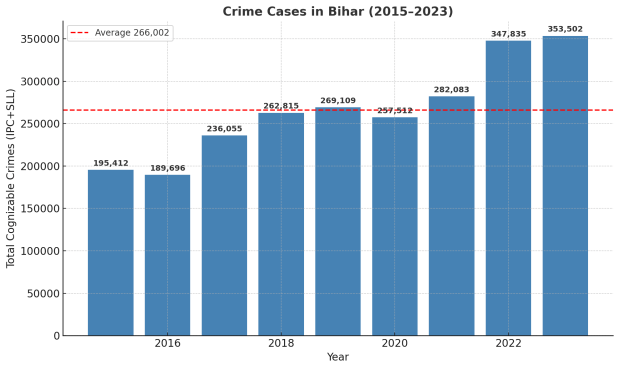

When Nitish Kumar took charge of the Chief Minister office in 2005, the NCRB data pointed to an initial decline in the number of murders. Whereas if we compare the crime data to the time since Nitish Kumar’s governance, the rate has shockingly increased 42% from 2010 to 2015 after the slowdown witnessed from 2000 started fizzling out. According to NCRB and Bihar Police annual reports, kidnapping cases linked to forced marriages nearly doubled, rising 98% between 2010 and 2015 with thefts up 90%, while riots increased 73% in the same period.

From 2005 to 2015 the NCRB and Bihar Police data suggests 1.68 lacs average cognizable crimes per year. In the last decade the crime rate has surged significantly to 2.66 lacs per year

In its defence, JD(U) claims the increase in numbers was due to an increase in reporting of cases and more trust in the police to investigate the crime.

In 2023, defending his regime against criticisms about rising crimes, Nitish Kumar said, “The crime incidents are under control … look at the figures … it is much lower than the other states. They (BJP leaders) are unnecessarily creating hype around the crime rates of Bihar.”

Nitish Kumar’s liquor ban card

“When you look overall, after the ban on liquor, crime in the state has gone down … we will not rest till the guilty are punished.”

Contrary to the official data around crime cases in Bihar CM Nitish Kumar has always credited his decision to ban liquor in the state to fall in crime.

Despite multiple opposition from both political parties and people of the state he has refused to lift the ban. Multiple cases of deaths due to spurious liquor further intensified his action against the liquor mafias in the state.

The ban was introduced in 2016, and till August 31, 2024, the state recorded over 8.43 lakh cases under the Bihar Prohibition and Excise Act. A total of 12.79 lakh people were arrested during the same period, said the then excise and registration department secretary, Vinod Singh Gunjiyal.

While the ban has led to significant loss to the state exchequer, and multiple deaths were also reported due to spurious liquor cases – the Nitish government stood firm on the decision. As a drawback, drug consumption has grown multifold in the state. From 518 in 2016 to 2,411 in 2024, the consumption shows a shift from alcohol to other substances.

Fodder Scam – The ‘Chara Ghotala’ story

Lalu Prasad Yadav’s biggest setback came with the unravelling of the fodder scam, worth nearly ₹1,000 crore, which exploded in the mid-1990s. Though the corruption spanned over two decades (1970s–1996), it surfaced only in the mid-90s. Fake bills and vouchers were raised in the name of supplying fodder, medicines, food and equipment for cattle through the Animal Husbandry Department, but the supplies never existed. Instead, the funds were siphoned off and withdrawn from treasuries in Chaibasa, Dumka and Ranchi. The case was eventually handed over to the CBI.

After months of investigation, the CBI filed a chargesheet against Lalu in 1997. Forced to resign, he installed his wife Rabri Devi as Chief Minister. The scam eventually branched into more than 50 cases, implicating IAS officers, suppliers, and politicians. Lalu was convicted in several of them, including the Chaibasa, Deoghar and Dumka treasury cases, and sentenced to a total of 14 years in jail. He was released on bail on health grounds in 2021 but was later arrested again, with his disqualification from contesting elections continuing to this day.

Development and Bihar – Are they two poles apart?

In early 2000s, a report of the World Bank described Bihar as being at the “bottom of almost every development indicator” in India. In normal conversations, Bihar was always seen as a place with everything in the worst form – a backward state. The weak industrial development forced people from Bihar to look for opportunities in other states – leading to a huge migration phenomenon. Despite being in power for over a decade Nitish has still not been able to pull out the state into a progressive category. Bihar has the lowest per capita income in India — ₹59,637 in FY23 against the national average of approximately Rs 1,72,000.

The state has largely been dependent on the agriculture sector, battling poor infrastructure, roads, electricity supply and one of the worst healthcare systems in the country.

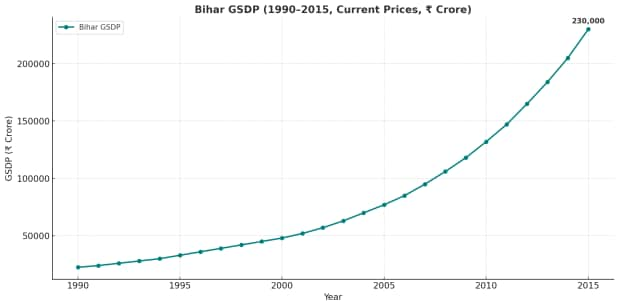

In the late 1980s, around 46% of the state’s income was from the agriculture sector. Official data of the government shows the state’s GDP grew at an average of 5.1% annually, below the national average of 7.3% during 1999-2008. Limited industrial growth and heavy dependence on agriculture kept the per capita income low and development slower.

The per-capita income during 1990-91 was approx. Rs 2,660, which increased to Rs 7,914 in 2004-05. In 2023-24, the per capita income in Bihar was Rs 36,333 at constant prices and Rs 66,828 at current prices, according to the Bihar Economic Survey 2024-25 tabled in the assembly in February this year.

Data suggest that in the last 20 years, the state has seen a surge in the rate of road and highway construction. The state’s economic survey stated that Bihar recorded the third highest growth (7.6%) in the transport and communication sector during 2011-24 period. The top two states were Uttar Pradesh (10.1%) and Karnataka (7.7%). During this period the rural paved roads increased from 835 km to 1.17 lakh km.

Though conditions improved with push from protests and needs, the condition of hospitals and medical facilities are still a major concern in the state. Multiple reportages have been done on the poor state of the hospitals with dogs, mice roaming while critical patients lay on bed.

Furthermore, the industrial development has not effectively taken place, except for the capital Patna.

Caste empowerment and social justice

Lalu Yadav and Nitish Kumar, both have been two pillars of Bihar’s politics and they even worked together on several fronts, only to part ways later. One of the key areas the two have always spoken, and worked is – caste issues. It is not hidden from anyone that Lalu Yadav is seen as one of the most prominent OBC leaders in the post-Mandal Commission era. He came out as a defender of other backward communities and other minorities.

It was this time when ‘Bihar me rahega Lalu’ slogan made headlines, signalling his intense grip on the issue.

Nitish Kumar has also tried positioning himself as the well-wisher of the backward communities and women especially. It is believed the reason for Nitish Kumar continuing as CM with the Mahagathabandhan, and then with NDA is because of the impact of him as a leader on the two sections – women and backward communities. It is no surprise that the opposition’s campaign has also focused on the two sides to propel their agenda.

Social policies

Both Nitish and Lalu have been ardent supporters of caste-based reservation and Nitish Kumar even stood against the Centre on the issue of caste census. His government declared and proceeded with the caste census, the report of which was tabled in the Bihar assembly as well.

According to the research data of the Institute of Human Development, the population below the poverty line (both urban and rural) stood at 54.96% in 1993-94. This decreased by 12.36% and reached 42.60% in the next six years during 1999-2000. As per Tendulkar committee methodology, it reduced to 33.7% during Nitish Kumar rule in 2011-12.

However, the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) of the NITI Aayog in 2021 stated that more than 50% of the population of Bihar was identified as “multidimensionally poor”. At the time, the state had the maximum percentage of population living in poverty among all the States and the Union Territories in the country.

In the past 18 years, the expense on the education sector has increased 10 times and the same on both health and social services sectors have gone up by 13 times. The dropout rate from the government secondary schools declined by 62.25% in the past five years.

Bihar’s political journey continues to be narrated through the binaries of “jungle raj” versus “sushashan,” yet the lived reality of its people lies somewhere in between. Lalu Yadav’s era left behind the indelible scars of lawlessness, criminalization of politics, and the fodder scam, even as he positioned himself as a champion of caste empowerment and social justice.

Nitish Kumar, who came to power on the promise of restoring law and order, has undoubtedly overseen improvements in governance, infrastructure, and reporting mechanisms. However, rising crime numbers, the polarizing liquor ban, and persistent poverty show that his model of sushashan has not been free of contradictions.