Does India have a chance to be the next China? Will a booming stock market and the Centre’s new trade deals help India grow as rapidly over a period of time and become as large and as rich as China is today? With China’s economy slowing and the West seeing it more as a rival than an economic partner, India might have a chance to take its place as the world’s next growth driver. China’s economy grew much slower than expected in the second quarter with a protracted property downturn and job insecurity squeezing domestic demand. China’s economy grew 4.7 per cent in April-June, per official data, which is its slowest since the first quarter of 2023, missing Reuters’ estimates of 5.1 per cent. It was also down from the 5.3 per cent expansion in the previous quarter.

In the past couple of years, the economic fortunes and outlook for China and India was divergent. After the pandemic, China’s economic recovery has been weak while India’s has been strong. China is also facing many structural challenges including a rapidly aging population while India has a relatively young and rising labour force and a far friendlier external environment.

In a report, UBS Securities examined the key factors which, if they play well, can help India grab this opportunity to take China’s place. The report provide a framework for the following implied questions: 1) can India become a manufacturing powerhouse like China and, potentially, export like China; 2) can India’s domestic market grow like China’s did in the past two decades; and 3) will India’s growth have similar implications for the global commodities and energy markets as China’s has had?

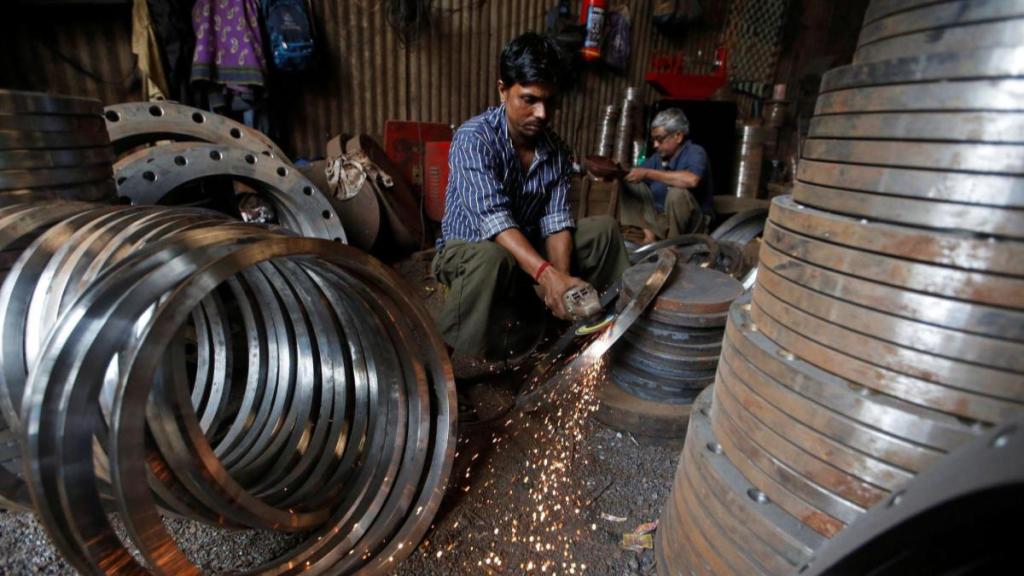

Manufacturing prowess in picture?

Even with the government’s ‘Make in India’ initiative in place, with a relatively small manufacturing base, UBS Securities said that India is unlikely to seriously challenge China’s overall manufacturing position soon. However, it added, India has some potentially favourable conditions for rapid growth in manufacturing including abundant cheap labour, improving infrastructure, policies to attract foreign investment and a mostly favourable international image. A notable difference, UBS Securities added, between India and China is their economic structure, in particular the importance of manufacturing. While China’s economy was already more manufacturing based, India traditionally has been a much more services-based economy and its manufacturing is about 13 per cent of GDP today, while services account for over 50 per cent.

Notwithstanding the difference in manufacturing’s starting position, how does India compare to China in some key factors commonly recognized as having driven the latter’s manufacturing sector growth? Tanvee Gupta Jain, Chief India Economist at UBS Securities, said, “Favourable demographics has often been cited as an important reason for India’s future growth, just as the abundance of young and cheap labour boosted China’s manufacturing competitiveness two decades ago.” While China’s total employment was 720 million in 2000, India’s is only about 550 million today, due to the low participation of women in India’s labour force but it still has potential to expand the manufacturing employment notably if female labour market participation rises significantly.

Further, while infrastructure has been a long-standing challenge in India, the country has been consistently investing in transport infrastructure and related areas in the past 10-15 years.

UBS Securities also stated that foreign investors seem to be voting with ample confidence in India. Foreign direct investment into India has been rising, partly due to the ongoing shift in global supply chains, and partly attracted by India’s large domestic market. “Annual FDI in terms of fresh equity inflow to India reached US$56 bn in FY20-22 from an average US$41 bn in the past five years, although it slowed to US$45 bn in FY24, with manufacturing FDI accounting for over one-third in the recent couple of years. This compares with around US$50 bn for China in the early 2000s, although manufacturing FDI accounted for about two-thirds of total FDI inflows. The difference in FDI into manufacturing between China twenty years ago and India now may lie in the different structure and size of manufacturing in the two economies,” said Tanvee Gupta Jain.

In terms of land acquisition rules, UBS Securities said that while the progress is slow, in recent years, both India’s central and state governments have been focusing on land reforms in the form of: 1) creating landbanks for easily identifiable industrial projects; and 2) moving the purchase process online (except for very large parcels) via a land information system, ensuring higher transparency; and 3) digitisation of land records.

Tanvee Gupta Jain said, “A very important factor and favourable condition for India’s manufacturing development is its large domestic market, which is now bigger than China’s back in 2000 in constant USD terms. Therefore, even though in the global market, India may face tough competition from China and ASEAN economies, its large domestic market is the key to rapid manufacturing growth in the years ahead. In this process, India stands a good chance of closing the gap with China in manufacturing and taking some market share away from China internationally.”

A possible surge in domestic consumption to drive growth

India has a large domestic market that is now equivalent to China’s around 2006-2007, which will be the key to rapid manufacturing growth in the years ahead. In this process, UBS said, India stands a good chance of closing the gap with China and taking some market share. “India’s household consumption doubled in the past decade and UBS expects India to overtake Japan in 2026 to be the 3rd largest consumer market. If India’s consumption grows at a similar pace as its GDP, the country’s domestic market size could reach China’s current level many years before its GDP does,” said Tanvee Gupta Jain.

Will India’s energy and commodity demand grow like China’s?

China has had an enormous impact on the global energy and commodity market over the past two decades. India is already a large oil and coal importer but per UBS, it’s unlikely to see a similar demand growth from India in the coming years. “India’s economy is less focused on industry than China’s has been and its growth is unlikely to be capital- and energy-intensive. India’s own resource availability and different urbanization pattern also means the country is unlikely to follow China’s past path in imports of base metals such as Iron ore,” the UBS report stated.