Maharashtra’s chief minister, Devendra Fadnavis, has announced that Maharashtra state has suffered a drought in 2018 and that the state is seeking drought relief of Rs 7000 crore from the Centre. This raises several questions: Firstly, what happened to the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY), which was supposed to compensate farmers in case of a drought year? Why does the state have to knock at the doors of the Centre for drought relief as if there was no crop insurance? Secondly, what happened to massive irrigation investments that the state had been making over the last fifteen years or so in drought-proofing its agriculture? That obviously seems to have failed. Thirdly, if Maharashtra is to be compensated for drought relief, why not other states that had similar droughts or even worse? For example, during monsoon 2018 (June 1 to September 30), while Maharashtra’s Marathwada region experienced 22% lower rainfall than normal, Madhya Maharashtra was only 9% below normal. In comparison, rainfall in Gujarat was 24% below normal and in Saurashtra and Kutch, it was 34% below normal. In Rajasthan it was 23% below normal and in north interior Karnataka 29% below normal. Even Bihar, Jharkhand, Assam, Meghalaya, and Arunachal Pradesh all experienced deficiency of more than 20% compared to their respective normal rainfalls. All of them should be then approaching the Centre for drought relief.

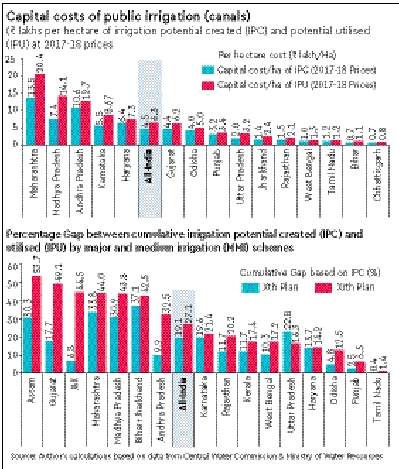

But, here we focus on public expenditure on irrigation, and in particular, major and medium irrigation schemes (MMI), their costs and benefits, and what could be the possible alternative policy options to protect farmers’ incomes from the vagaries of nature, especially in a state like Maharashtra. We look at the yearly expenditure during 2002-03 to 2013-14, convert them to 2017-18 prices using all India wholesale price index, cumulate these expenditures and divide them by the cumulative irrigation potential created (IPC) and utilised (IPU) during that period to find out the capital costs of canal irrigation in all major states that have created at least one million hectares of additional irrigation during this period (2002-03 to 2013-14). Our analysis is limited upto 2013-14, as there is no information on IPC and IPU after 2013-14 even with Central Water Commission or ministry of water resources. While yearly expenditures are known, no one knows whether these have created any additional irrigation. Progress is measured by expenditure, not by whether farmers have received any water or not!

Let us look at the results. The attached graphic gives state-wise capital costs of public irrigation (canals, primarily through MMI schemes). Maharashtra tops the list with Rs 20.4 lakh/ha of irrigation potential utilised (IPU) compared to the all India average cost of just Rs 6.3 lakh/ha of IPU. The costs per hectare of IPC are somewhat lower, but Maharashtra is still the highest at Rs 13.5 lakh/ha. While the engineers and contractors are quick to announce IPC after construction of reservoirs and main canals, farmers benefit only when this potential created is converted to potential utilised, which is to be ensured by ministry of agriculture and farmers’ welfare.

One can give several reasons for high costs of public irrigation in Maharashtra, ranging from its tough topography to the widening gap between its IPC and IPU to rampant corruption. But the fact remains that these costs are so high that one is forced to think whether any investments in public irrigation in Maharashtra is worth making without bringing in transparency and accountability in terms of benefits and costs. Why we say this is because the profitability in crop cultivation from public irrigation hardly matches with the opportunity cost of public irrigation. For example, if say, Rs 20 lakh (equivalent to the cost of public irrigation on IPU basis), were given to each farmer on a per hectare basis as long-term bonds with a fixed interest of say, 8%, per annum, they would have received a net annual income of Rs 1.6 lakh without any risk. The question to ask is whether the existing farmers who have access to public irrigation are making this much (Rs 1.6 lakh/ha) as net income. The analysis based on cost of cultivation studies does not support this. It is thus very clear that the benefit cost (B/C) ratios of most of these projects do not justify these projects. But, as the system functions, the B/C ratios are highly inflated in feasibility reports to justify starting several projects, money is splurged, and hardly any ex-post analysis is done to see whether what was promised gets delivered at that cost, and whether the benefits have turned out to be commensurate to costs. In sum, public irrigation needs major over-hauling in the country, especially in states like Maharashtra. The money seems to have disappeared as water disappears in sand.

Also, there is the question of who uses how much of irrigation water. In Maharashtra, although about 19% of gross cropped area is irrigated, in the case of sugarcane, it is 100% and in case of cotton just 3%. So there is massive inequity in the distribution of irrigation water in the state. Can the Fadnavis government take up this challenge and distribute irrigation water from public canals more equitably among farmers, on a per hectare basis? If everyone gets equal access to canal waters, it could lead to emergence of water markets among farmers, encouraging more efficient cropping patterns with respect to water. Only then one can say ‘more crop per drop’.