In a refreshing departure from the norm of the Modi government, the Chief Economic Adviser (CEA) has predicted that the Indian economy is on course to grow at about 6.5% a year during the rest of the decade. Mr V Anantha Nageswaran is a modest man. He was appointed as CEA on January 28, 2022 and has, mostly, maintained a low profile and spoke only occasionally. In recent weeks, he has been more forthcoming and I welcome that.

In an important statement at Kochi on Monday last, the CEA said:

“India will be able to achieve 6.5% GDP growth in the remaining years of this decade, despite the headwinds and turbulence in the global economy. …The growth in the digital economy and investments would also enable the country to achieve an additional 0.5 to 1% growth …”

Evidently, the government is no longer expecting ‘double-digit growth’ which was its pre-pandemic boast. Nor will the government emulate the golden period of growth between 2004 and 2010 (the ‘boom years’ according to the former CEA). The size of the GDP, in constant prices, at the end of 2022-23 has been estimated to be $3.75 trillion. If the economy grows at 6.5% a year, the goal of reaching $5 trillion, already pushed back from 2023-24 to 2025-26, will be further pushed back to 2027-28.

Who is responsible?

A modest rate of growth is due to both domestic factors and the external environment. We cannot control the external factors, we can only cope with them. For example, the Russia-Ukraine war and the deliberate cuts in oil production made by oil-producing countries are beyond our control. If the war continued or oil prices rose, we will pay a price in terms of slower GDP growth. No one can or will blame the government for the adverse impact.

On the other hand, domestic factors that affect the rate of growth are the government’s responsibility. A government must be fleet-footed and resilient to manage these factors. What we have seen in India is that the growth momentum was lost due to demonetisation in November 2016. The growth rate slowed down in 2017-18, 2018-19 and 2019-20. Then, there was a black swan event — Covid-19. The economy was practically shut down. Prolonged lockdowns, a delayed roll-out of the free vaccination programme, insufficient fiscal support to micro, small and medium enterprises and government’s stubborn refusal to make cash transfers to the very poor exacerbated the situation. Thousands of industrial units were closed down and hundreds of thousands of jobs were lost forever. Millions started their long walk to their homes in distant states, hundreds died on the way. Nevertheless, the government persisted with supply side measures and refused to look at the factors that affected demand.

Unremarkable recovery

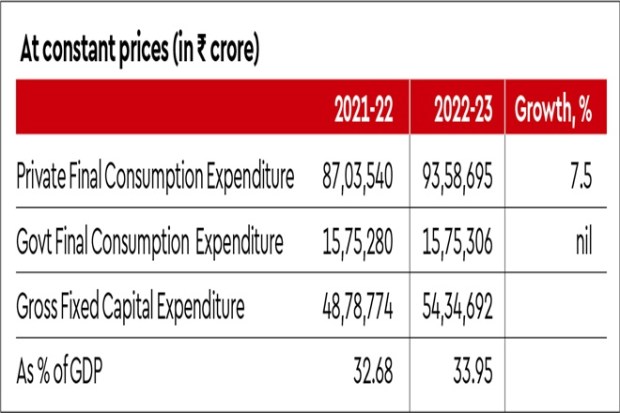

As a result, the recovery after the pandemic has been weak and shallow. The numbers tell the story (see table).

The total consumption expenditure, private and government, grew by just 6.3%. While gross fixed capital expenditure increased by 1.3%, the GDP growth rate for the whole year fell from 9.1% (in 2021-22) to 7.2% (in 2022-23). It is a fact that consumption, rather than capital expenditure, that drives growth in India. Sluggish growth in consumption pointed to less money in the hands of the people or high prices or more pessimism about the future — or all of the above.

Also read: Across the aisle by P Chidambaram: Sengol that must not bend

By economic activity (GVA), except ‘Agriculture’ and ‘Financial & Professional Services’, the growth rate of every sector in 2022-23 was less than the growth rate in 2021-22. ‘Mining & Quarrying’ grew by 4.6% in 2022-23 (as against 7.1% in the previous year); ‘Manufacturing’ grew by a dismal 1.3% as against 11.1%; and ‘Construction’ grew by 10.0% as against 14.8%. All three are labour-intensive sectors.

While retail inflation has moderated to 4.3% in April 2023, we are not out of the woods yet. Mr Shaktikanta Das, Governor, RBI, has cautioned that “as per our current assessment, the disinflation process is likely to be slow and protracted, with convergence to the inflation target of 4% being achieved over the medium term.” He added that “regulators cannot be oblivious to growth concerns given the outsized addition to the workforce every year.” CMIE reported that the Al-India unemployment rate was 8.11% in April 2023 even as the Labour Participation Rate stood at 42%.

Also read: Across the aisle by P Chidambaram | Balasore: Man-made disaster

The 6-5-8 syndrome

There was a time when policy makers in India had ‘settled’ for 5% growth and 5% inflation. That resulted in millions of people remaining poor and India rapidly falling behind China and other South-East Asian neighbours. I am afraid something of that kind is happening now. The present policymakers boast of Amritkaal, but no longer speak of 8-9% growth. They seem satisfied with 6% growth, 5% inflation and 8% unemployment. These numbers spell disaster for India. They mean massive poverty, rising unemployment and growing inequality. India will not become a middle-income country for many years.

We must re-set our goals. We must aim at achieving 8-9 growth quickly and aspire to double-digit growth. Those goals seem beyond the capacity of the present policymakers and rulers.