Earlier this month, the Union ministry of culture held an international conference in Greater Noida, at the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, calling for experts to share their research on the undeciphered Indus script. Prior to that, Tamil Nadu chief minister MK Stalin had also announced a prize money to the tune of $1 million to anyone who would be able to decode the script. Several attempts have been made by historians and linguists around the globe, but even today the Indus script from Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro is an enigma.

Different scholars have attributed the script to different origins and deduced different meanings. However, a definitive key for the Indus script has been elusive.

Elusive key: Hypotheses on the Indus script’s origins

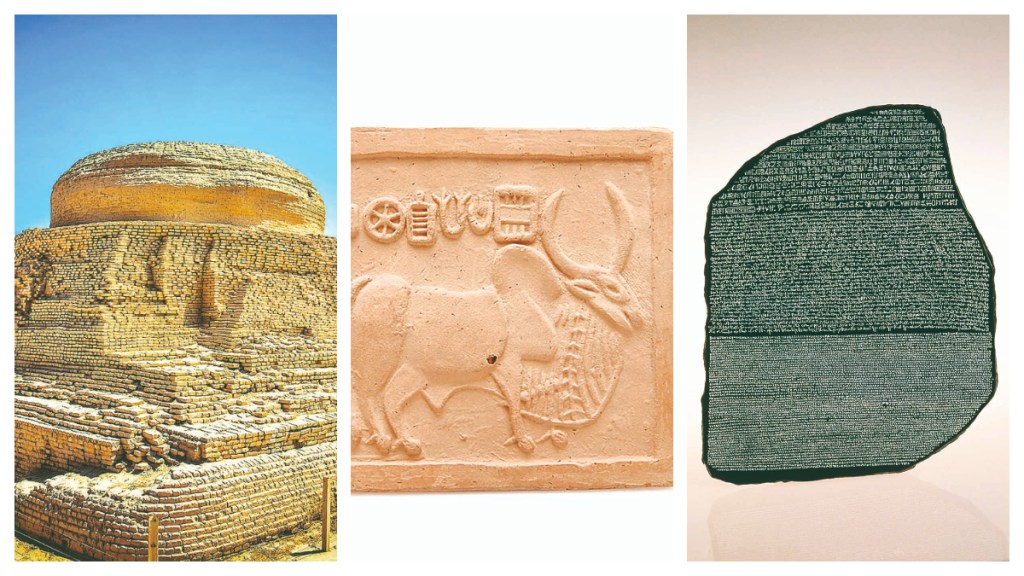

Earlier in September, a meeting was held and a panel of experts were brought together to share their research findings about the Indus script. From archaeologists and engineers to computer scientists and doctors, all were invited to present their research, given that the Indus script is a script from one of the oldest civilisations to exist. Like the Rosetta Stone was discovered as a key to the Egyptian and Greek scripts, no such ancient key has been discovered for the Indus script. However, several hypotheses have surfaced, including a possible reference from a Rakhigarhi script scrawled on a seal found in 2023, as well as potential similarities to a Proto-Dravidian language, as has been pointed out by a few scholars. Others have argued for Sanksrit or Vedic origins for the script, borrowing signs and motifs bearing similarities to the Rig Veda

Global lexicon of mysteries: Undeciphered texts beyond Harappa

Notably, the Indus script, or the written and spoken language of the Harappans, is not the only one that is still stuck in translation. There are Indian languages of which the origins are still unknown, as well as languages that are still spoken in parts of the country, but have no written scripts, like Konkani and Coorgi. Other cultures, too, have similar examples. Linguists and researchers are still awaiting clarity on Linear A, a Minoan language, used by the first civilisations to inhabit the island of Crete, for which no decoding of the script has been achieved.

Even though it is presumed that another language used by the Mycenaeans, or the Bronze Age Greece, was derived or took inspiration from Linear A, and was, therefore, called Linear B, the origin and translation of the former has not been discovered as yet. Sounds and purpose of many of the symbols used in Linear A are still unknown. The Chilean Easter Island, also known as Rapa Nui, had a language called the Rongorongo, which found its first mention in public discourse in the late 1800s. A script that has all of 120 symbols or characters remains a mystery still, while the monolithic Moai statues on the island stand as proof of the ancient culture. The Rongorongo is a script that although more brief and recently discovered than many other scripts, is still an enigma that is being studied and deciphered by scholars. Like Rongorongo, the Cypro-Minoan script from Cyprus, dating back to the 11th century, has only 200 brief surviving texts, which scholars have said make attempts at translation very difficult.

Older still than all others mentioned here are the Vinca symbols, dating back to 5500-4500 BCE, even prior to the Mesopotamian culture. Although it was widely agreed that ‘writing’ began with the Mesopotamian culture, the symbols used by the Vincas are still a big question mark for linguists. A civilisation that stemmed from the Danube valley in South-East Europe, the Vincas are said to have brought technological advancements like spinning, weaving, and leatherwork. The Proto-Elamite writing system, also among the oldest and almost 5,000 years old, was spoken in Iran, and is yet to be deciphered. The few remaining texts in Proto-Elamite are currently preserved in the Louvre Museum; they have also been digitised in order for researchers to have easier access to the materials in the future.

With the sheer number of texts across the globe that are still undeciphered, one wonders how many pathbreaking inventions or discoveries us 21st century civilians will never know about until the texts are decoded, perhaps in this generation, or perhaps many years later in the future. Cultural contexts, ways of living, familial and power structures, interpersonal relationships and more may have found mention in the scribbles and lines etched onto stones that seem completely alien to those of us used to consuming content in text, image, video, and audio formats.

Educational institutions, museums and well as governments around the globe are taking efforts to not only preserve these texts, but are dedicating resources to push for research so that these languages may be deciphered, as well as investing in detangling and better understanding their own history. As for the ministry of culture and their recent push for research on the Indus script, it remains to be seen how far this initiative goes and how successful it ends up being. Will we have deciphered the Indus script in the years to come? With hundreds of years already passed, it’s a question for the ages.