The packages are mounting. They are everywhere. We see the atrium of an electronics market in Shanghai, where ordered goods are being boxed, taped and prepared for dispatch. We see nothing but the parcels, hear nothing but the sound of tape unrolling and tearing. It’s as if a concert is being performed by the workers, where the sounds blend into an orchestra. This is the Opera of Trade and Commerce, on display at the ongoing ninth edition of Serendipity Arts Festival in Goa. And, while Swiss artists Marianne Halter and Mario Marchisella capture a Chinese establishment, it is true of the world as well, particularly India, where the list of goods delivered in ten minutes grows longer by the day.

We are a consumerist society, and the billions of packages piling up at airports and dispatch centres daily, waiting to be delivered, can’t be reminder enough.

Damian Christinger, curator of Ghosts in Machines, of which Opera is a part, says: “We just see our packages. We don’t see the delivery person. Do you even know the name of the person who delivered a package last to you? I hear in Delhi you can order anything in, what, 10 minutes? This, by the way, is not true of Europe, yet.”

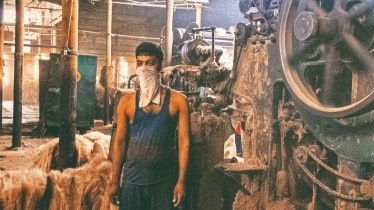

Exploitative labour practices are nothing new. Sonia Mehra Chawla, in her work Paat (Jute), builds a narrative of colonial capitalism and legacies using Bengal’s jute industry as a trope, sketching the working and labour class since the colonial era to contemporary times. “A man standing in a jute factory, masked, depicts the facelessness of the labour,” says Christinger.

Trade and Commerce indicate a consumerist society

Building on the idea of past dreams and uncertain futures, Ghosts in Machines stresses that what was once a symbol of progress—factories, power plants—are now symbolic of pollution and climate change. “The whole idea of progress has become a ghost today,” says Christinger.

The Power Plant, which depicts a ruined power plant, haunted by the ghosts of its former operators, is reminiscent of the broken promises of modernity. Artist Ravi Agarwal asks uncomfortable questions. “In the name of modernity, where we built projects of various kinds, we are blind to the violence against ecology. We make a world only for ourselves, seeing it only with human gaze. We are just one species on this planet. How much pain do we cause others? Can the world ever be non-anthropogenic?”

Carbon: Lifegiver, doomspeller

Carbon credits, carbon offsets, carbon footprint, carbon dioxide, carbon sink… there is perhaps no element as viled as carbon in this age of climate grief. Yet, over 541 million years ago, it was a carbon molecule that combined with a hydrogen to form an elemental hydrocarbon, the genesis of life, as we know it, on earth.

Carbon is life. Today, carbon is also death.

And at a time when it has become a dirty word, it is also imperative for us to be reminded that we all are essentially carbon and the element is the backbone of everything that symbolises life and energy. Conceptualised by the Science Gallery in Bengaluru, an exhibit titled Carbon, at Serendipity Arts Festival, immediately pulls a science lover, and enlightens even those who understand little what the fuss is all about.

The ideas in question are of a consumerist society, wasteful consumption, the excessive use of fossil fuels, the ubiquity of plastic, and the inevitability of it all.

Curator Ravi Agarwal says we need to think of science in a political and social context too. “Carbon is the building block of life. But the way we demonise it, making it the big villain, is not nature’s fault. How we have exploited carbon is human doing. Carbon did nothing wrong by itself.”

The audio-visual cacophony of hydrocarbon chains portrayed in film by artist Marina Zurkow sounds irritating to a viewer, but why does not the pervasiveness of physical manifestations of the same chains—as seen in plastic to fossil fuels—not bother us? It’s claustrophobic, and it’s out of control, the artist reminds us.

Scientist and artist Jan Swierkowski’s thrilling digital arcade game X-Carbon enables you to be saviour of the galaxy by harnessing the rebellious matter on a dying star and saving civilisations nearby. But, can we save our planet first?

Agarwal says the idea was to make science more interactive, people-friendly and to demystify it, even if through a video game.

Fungi growing on a discarded chair questions our wasteful consumption in artist Maria Joseph’s The Mycobloc Chair.

Nothing better demonstrates the irony of things than researcher Annelie Berner’s work Clouds Above, Clouds Below, that as climate change alters characteristics of clouds in the sky, the extensive research on finding solutions to these issues, climate included, just uses up more power, data, and digital clouds.

The recent COP29 in Baku, where several participants arrived on private jets, burning up copious fossil fuel, and generating a huge carbon footprint, just to deliberate on how to minimise use of fossil fuels and reduce carbon footprint, would have been laughable if it weren’t so unfortunate.

The process of finding sustainable solutions is itself not a sustainable one! And, that is the tragedy of the times we live in.

Alchemy and Auschwitz

This is how it happened. This was the apparatus used.

The numerous flasks, pipettes, funnels and test tubes… in which amethyst blue Zyklon B, used in the gas chambers of Treblinka and Auschwitz, was synthesised. An accidental discovery of prussian blue, the first chemically made colour, which then was used to make prussic acid, better known as cyanide, from which was synthesised amethyst blue—all happened in a chemistry lab. But it was more chymstry (alchemy), as a result of which medicine morphed into murder. Ajab Karkhana by award-winning Ethiopian artist Shebha Chhachhi explores the manipulations of knowledge in a lab for human profit, the machinations of the pharmaceutical industry, bringing to light its epistemic corruption, environmental contamination and epidemic contagion, which we all were at the receiving end recently with Covid.