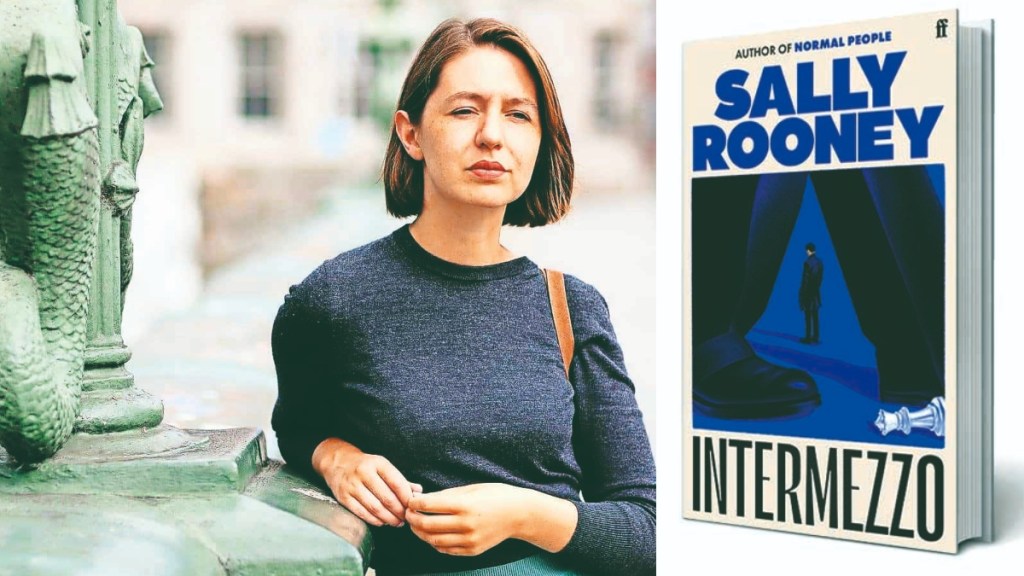

If there’s one thing about Irish author and screenwriter Sally Rooney’s latest work, Intermezzo (2024), it’s that, gun to head, her characters won’t be able to pass the Bechdel test—which evaluates how women are featured in a work of fiction as a measure of gender representation.

Does it bug me? You bet. Is it something that’s irked me in her previous works? 100%. Do I still go on reading her books anyway? Of course. It’s, I believe, rooted in something my colleague said in passing recently. Rooney is like the Taylor Swift of the publishing world. You can hate her, but you can’t ignore her or the loyal reader base that she’s amassed.

Intermezzo, Roon-ey’s most recent book, follows the lives of two brothers—Peter Kou-bek, a 32-year-old Dublin-based ‘successful’ lawyer, and Ivan Koubek, a 22-year-old competitive chess player who we are told is a socially awkward loner. The book begins a few weeks after the two lose their father to a long-term illness, both grieving, both trying to navigate their lives, and wondering how life simply goes on irrespective of the fact that you just lost your father.

The grief lingers on throughout the book, but as they both attempt to move on and go back to regular programming, Ivan meets an older woman at a chess event, 36-year-old Margaret who’s still enmeshed in a complicated relationship with her former husband. Hesitant of their age gap at first, the two quickly fall in love, realising that they both belong to the ‘same camp’.

Peter, too, tries to make sense of his relationships with his former partner Sylvia, with whom he broke up with many years ago, but is still in love with, and 23-year-old college student Naomi, who we’re constantly reminded used to dabble in some sort of online sex work.

Even as Rooney takes turns to narrate the story through Peter, Ivan, and sometimes Margaret’s perspectives, the women aren’t the strongest suit in the book. It’s understandable that when Peter and Ivan take control of the narrative, we’d get to know more about their lives, their emotions, and their struggles. But it feels that the women are reduced to simply elements that are only present to validate what the Koubek brothers are feeling, be submissive with them in bed, and further the plot. More so in Naomi’s case, who’s often spoken about in ways that sound only transactory.

What’s interesting also is that Rooney, a Marxist, seeps in some political issues of present-day Ireland in the book through different characters. However, these are so subtly woven into the verse that people who might not have context won’t probably pay heed to them. For instance, Peter’s substance abuse problem, which towards the end of the book, lands him in a public washroom trying to pour vodka in a lemonade bottle. Or the fact that there’s a housing crisis in Dublin, or Ivan’s internal conflicts about getting paid to evaluate data for a company and not doing anything that has real-world impact while people sleep hungry due to food shortages.

Even the stigma attached to the age gap aspect of their relationships is never truly delved into, the social implications for the women are left to the reader’s imagination.

However, there’s one thing that Intermezzo gets right to the dot. What the book sets out to do is paint the picture of a sibling relationship that’s fragmented and was held together solely because of the presence of a parent, which now shatters completely in the process of grieving. And it achieves this beautifully.

Rooney’s real craft is exploring complicated relationships in ways that feel very real and tangible. There were moments in the book where Ivan talks about not being there for his brother that made me wonder how many times I’d been blind to the problems of my family, because just like the chess prodigy, I couldn’t think beyond my own self. The resentment that each of them had built up towards each other and their own selves makes for a compelling read.

The book’s last chapter then feels like a salvation. It redeems every other perceived flaw—be it the long monologues as Ivan and Peter try to reflect on their own lives, the slow pace, and the somewhat strategic plays in Naomi and Peter’s story. For a novel that manages to capture the reader’s attention in all the right ways then, the only thorn sticking out is the lack of well fleshed out female characters, which seems to be something Rooney has totally abandoned in Intermezzo.