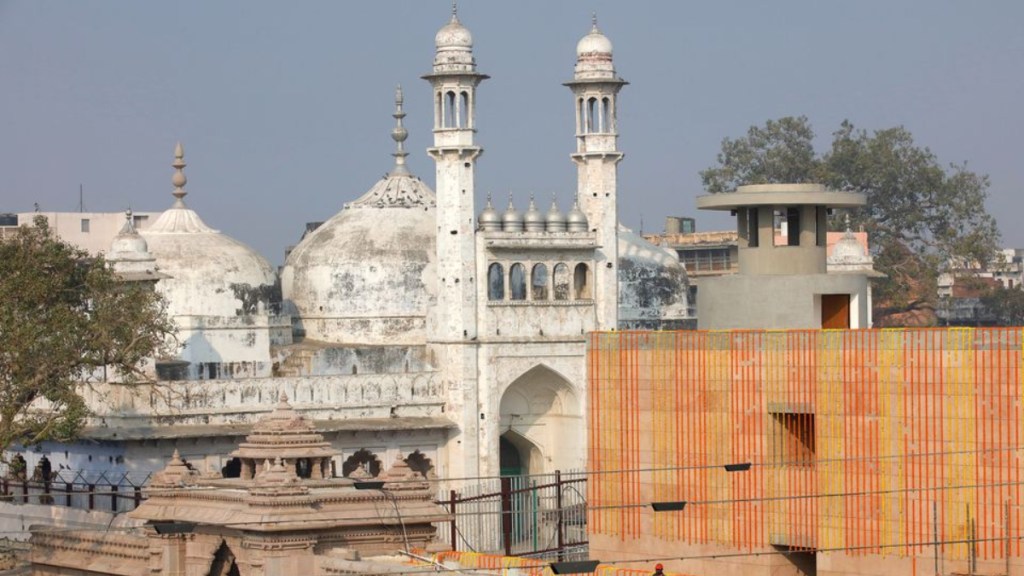

The court orders relating to Varanasi’s Gyanvapi and Mathura’s Shahi Idgah mosques have been criticised for “violating the Places of Worship Act 1991.” The Act itself has been challenged before the Supreme Court, and hearings will likely begin in the first week of January. Sarthak Ray takes a look at the Act and why it has run afoul of some

The Places of Worship Act

The Act preserves the religious nature and affiliation of a place of worship as it existed on August 15, 1947. Section 3 bars its conversion —no one is allowed to convert any place of worship that belonged to a religion or its sect on August 15, 1947, into the place of worship of another religion. Per Section 2(b), “conversion” includes “alteration or change of whatever nature.”

Also Read: SC has frozen the religious status of monuments as it was in 1947; lower courts should pay heed

Section 4 (1) preserves the religious character of a place of worship as on August 15, 1947, saying this “shall continue to be the same as it existed on that day.” Per Section 4(2), any legal proceeding regarding the conversion of the religious character of a place of worship existing on August 15, 1947, pending before any court, was to abate once the Act came into force.

Why was the law enacted?

The Act was brought by the PV Narasimha Rao-led government in 1991, against the backdrop of the communal tensions around the Ramjanmabhoomi movement of the late 1980s, which demanded a temple at the site of the Babri Masjid, a 16th century mosque. The movement’s leaders — including faces from the BJP and many mainstream Hindu outfits — contended that a temple once stood at the site and had been torn down by invaders who built the mosque. Several petitions had been filed demanding the site be handed over to Hindus.

Anticipating a spurt in similar movements and litigations in the future, the government of the day brought the Act to “effectively prevent any new controversies from arising in respect of conversion of any place of worship…”, in the words of then Union home minister SB Chavan.

Exceptions…

The Act specifically exempted the Ram janmabhoomi/Babri Masjid. In 1992, Babri was demolished by a Hindu mob. In 2019, in the title suit, the Supreme Court gave the land to the Hindus.

Also Read: Places of Worship Act 1991: No law above judicial scrutiny, says Amit Shah, days before SC deadline ends

The Act also leaves out sites covered under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites Act, matters settled by courts/tribunals before the Act, or mutually by the parties involved.

Act challenged before SC

Many petitions have challenged the Act in the courts. One, filed by advocate Ashwini Upadhyay, says that the Act violates the right to life and the right to religious freedom of the Hindus, Sikhs, Jains and Buddhists in its choice of cut-off date — as, since 1192, Muslim invaders and colonists destroyed many places of worship belonging to the former.

Another petition, by politician Subramanian Swamy, contends the Act’s exceptions should cover Kashi and Mathura.

Why has the Act been in the news recently?

The Act is the focal point of the challenge mounted to the petitions filed by Hindu interests in the Gyanvapi and Shahi Idgah matters. In both matters, the plaintiffs say that religious sites of immense importance to Hindus have been appropriated by the mosques.

In the Gyanvapi matter, where a group of Hindu petitioners sought the right to worship “visible” and “invisible” deities in the mosque premises, the Anjuman Intezamia Masjid Committee holds that this is “clearly interdicted” by the Act. But the judge who allowed the Hindu group’s petition observed that the Act “doesn’t operate as bar on the suit” since the petitioners “were worshiping… at the disputed place incessantly since a long time till 1993”, after which they were allowed worship once a year under the regulatory state of Uttar Pradesh.

In the Shahi Idgah matter, where the petitioners contend the mosque stands on the assumed birthplace of Krishna, experts say, the Act is likely to be invoked by the party challenging the order. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court’s Ayodhya verdict strongly endorsed the Act, calling it an instrument of “non-retrogression”, which is “a foundational feature of fundamental Constitutional principles, of which secularism is a core component.“