In a major breakthrough, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have developed a tiny implantable device that could save the lives of people with Type 1 diabetes by automatically delivering a life-saving hormone during episodes of dangerously low blood sugar, also known as hypoglycemia.

Hypoglycemia occurs when blood sugar levels fall to dangerously low levels, which can lead to confusion, seizures, unconsciousness, or even death. Currently, the standard emergency treatment is an injection of glucagon, a hormone that signals the liver to release glucose into the bloodstream. But during a crisis, especially if the patient is asleep, unconscious, or a child, it may not be possible to give the injection in time.

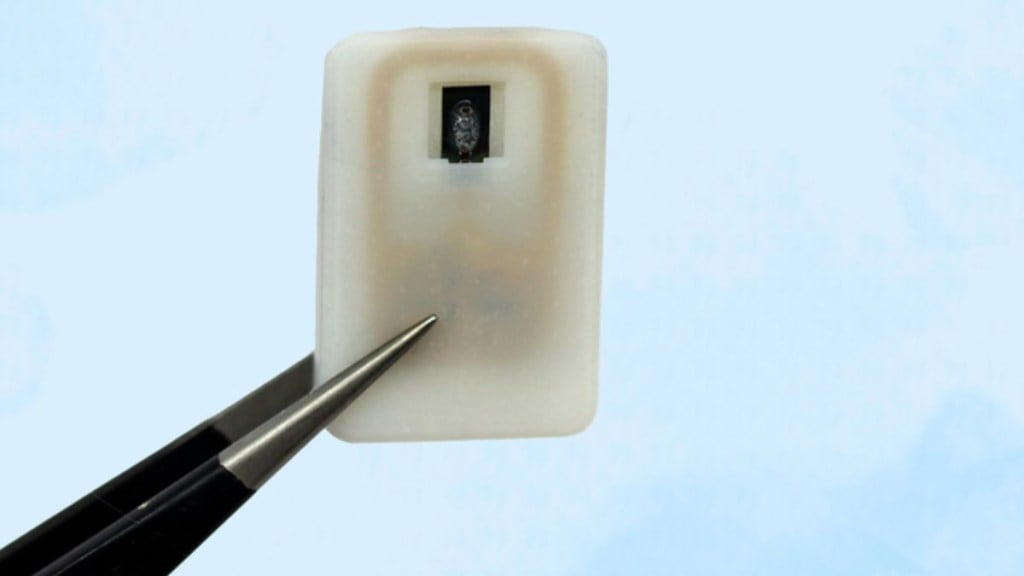

To solve this, MIT scientists have created a small device, roughly the size of a coin, that can sit under the skin and release glucagon when needed, no injection required. It can be triggered either manually or automatically by a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), which many diabetic patients already use.

How the device works

The implant contains a 3D-printed polymer reservoir filled with powdered glucagon, which is more stable for long-term storage than the liquid form. This reservoir is sealed with a special material called a shape-memory alloy, in this case, a nickel-titanium slab, that changes shape when heated.

When the person’s blood sugar drops too low, a wireless signal from a CGM or a manual remote triggers a small electric current, heating the alloy to about 40 degrees Celsius. This causes it to bend and release the powdered glucagon into the bloodstream.

“In our tests, blood sugar levels returned to normal in less than 10 minutes,” said Daniel Anderson, professor at MIT’s Department of Chemical Engineering and senior author of the study. “The goal was to build a device that’s always ready to protect patients, day or night.”

Tested in diabetic mice

To test the device, researchers implanted it in diabetic mice and used it to release glucagon as their blood sugar dropped. The animals’ glucose levels quickly stabilised, and hypoglycemia was successfully avoided. The team also found that the device continued working even after scar tissue formed around it, a common issue with long-term implants.

Not just for diabetes

Beyond glucagon, the device also shows promise for other emergency drugs. The team tested it with epinephrine, used to treat severe allergic reactions (anaphylaxis) and heart attacks, and saw similarly quick drug release and effectiveness.

“This could become a new way of delivering any emergency medicine quickly and precisely,” said Siddharth Krishnan, lead author of the study and now a professor at Stanford University.

What’s next?

So far, the device has been safely implanted in animals for up to four weeks. Researchers are now working on extending its lifespan to at least a year, after which it may need to be replaced. Human clinical trials are expected to begin within three years.

The study was published in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering and could offer hope for the millions living with diabetes and other conditions that require fast-acting medication.