Few Indian writers have captured the intimate, chaotic, and transformative pulse of democracy as vividly as Phanishwar Nath Renu did in his iconic novel Maila Aanchal. If elections in Bihar are so seductive, competitive, and realist, Renu’s novel remains their most luminous mirror. Written in the aftermath of India’s first general elections, Maila Aanchal (the Soiled Border) transformed the spectacle of democracy into a social ethnography of aspiration, manipulation, and awakening.

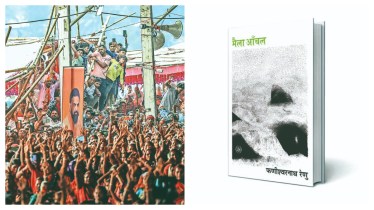

Through the microcosm of Maryganj —a village named after an Englishwoman, Mary, the bride of indigo-planter Martin, in Purnea district of north Bihar, Renu mapped the encounter between the state and the countryside, between the idealism of independence and the earthy, uneven rhythms of democracy in rural India. First published in 1954 by Samata Prakashan, Patna, and reissued in 1957 by Rajkamal Prakashan, Delhi, Maila Aanchal has gone through countless editions and is now a landmark of modern Hindi fiction. It earned Renu the President’s Award for the best Hindi novel of 1955 and was later adapted into Dagdar Babu (1977), directed by Nobendu Ghosh. Renu himself called it an anchalik upanyas, a regional novel marking a decisive break from the romanticised, utopian village of earlier nationalist writing.

What makes Maila Aanchal extraordinary is Renu’s linguistic imagination. He fuses standard Hindi with Maithili, Bhojpuri, Magahi, Nepali, Bengali, and Santhali, creating a living polyphony that captures the social and cultural pulse of rural Bihar. Drawing on what George Grierson famously termed the ‘Bihari languages’, Renu infused Hindi with their idioms, rhythms, and humour, transforming it from an elite, Sanskritised tongue into a democratised, desanskritised language of the people. His genius also lay in his ethnographic realism— recording how slogans, symbols, and ideologies travel through gossip, song, and rumour and in the sensuous boldness with which he depicted women and everyday life in the Maithili region.

Long before political anthropologists like Milton Singer described elections as ‘cultural performances’, or what Mukulika Banerjee calls a ‘ritual of democracy’, through which democracy is both performed and renewed, Maila Aanchal embodied that insight in fiction. Democracy arrives here not as an abstract constitutional promise but as a mela—a fair of voices, rumours, passions, and aspirations. Voters, party workers, candidates, and peasants become actors in a new theatre of hope and deceit, where politics seeps into gossip, song, and daily speech. When a villager exclaims, “ab vote hamra haath mein ba — malik ke na!” (Now the vote is in our hands, not the landlord’s!), Renu captures the subtle inversion of power relations that democracy promises.

Yet he also exposes its farce—the same villagers are soon seduced by liquor, caste appeals, and false promises. The ‘magic of democracy’ easily collapses into manipulation. Through this double vision—of magic and farce—Renu anticipated the ambivalence of Indian democracy itself. The Nehruvian dream of planning and progress falters against the stubborn realities of caste and inequality.

The schoolteacher and health worker, symbols of developmental modernity, remain powerless before entrenched hierarchies. Yet something irreversible has begun: an awareness of agency among the subaltern classes. This incipient social ferment in Maila Aanchal foreshadowed what Bihar would experience decades later—the Mandal revolution. When the Mandal Commission recommendations were implemented in the 1990s, the process Renu had intuitively chronicled reached political fruition. Caste hierarchies began to crumble as backward and Dalit castes claimed their space in public life with all its vibrancy and contradictions.

In other words, Maila Aanchal portrays Maryganj as a microcosm of not just Bihar’s, but India’s diverse polity, where caste and shifting party allegiances shape every form of political mobilisation. Divided into tolas—Rajput, Kayastha, Yadav, Tatma—each function as a distinct political constituency led by local power brokers who mediate between villagers and emerging parties through patronage and influence. Politics here is less ideological than transactional, driven by caste alliances and personal ambition. As one villager remarks, “ab logon ko chahiye ki apni-apni topi par likhwa le—bhumihar, rajput, kayasth, yadav, harijan!… kaun karyakarta kis party ka hai, samajh mein nahin aata” (People should just write their caste on their caps—Bhumihaar, Rajput, Kayastha, Yadav, Harijan! Who belongs to which party anymore—it’s impossible to tell), exposing the erosion of democratic ideals in newly independent India.

The novel unfolds through a vivid cast of characters: the idealist doctor Prashant and his beloved Kamla; Baldev, an influential Yadav and Congress worker; Mahant Sevadas; Bavandas, a regional Congress leader; Thakur Ramkirpal Singh, defender of Hindu orthodoxy; Kalicharan, the young wrestler turned socialist; Khalasi, the ojha and folk singer; and Jyotkhi, the Brahmin astrologer who distrusts modern medicine. Renu’s women— Lachmi, Mangala Devi, the teacher from the Charkha Centre, and Phuliya from the Tatma quarter—embody resilience and longing, their lives reflecting a countryside caught between faith, change, and the fragile promise of democracy.

Though Maryganj lies far from the centres of power in Patna or Delhi, the reach of Congress, socialist, and other political formations slowly penetrates its social life. Baldev, Bavandas, and Kalicharan personify competing ideologies—Congress pragmatism, Gandhian moralism, socialist idealism, and even the sectarian right wing ‘black caps’. Yet this democratic churn is shadowed by disillusionment, as ideals collide with entrenched hierarchies and elite manipulation. Doctor Prashant, once inspired by the dream of socialist reconstruction, ends in quiet despair: “Azaadi ke baad bhi kuch nahin badla” (Even after freedom, nothing has changed). Through him, Renu voices the waning faith in Nehruvian planning and development. The election, once a symbol of hope, becomes an instrument of survival.

Yet within that despair flickers the next chapter of Bihar’s politics. The socialist idioms that animate Maila Aanchal—samata, nyay, jan-shakti—would later shape the moral vocabulary of the Mandal generation. The post-Mandal era, inaugurated by Lalu Prasad Yadav’s assertion of OBC power, transformed Bihar’s political idiom from feudal deference to symbolic politics of caste pride.

Nitish Kumar’s politics of governance and social engineering—crafted in a pragmatic alliance with the BJP—dismantled the Jungle Raj and revitalised old networks by combining maternal welfare programmes with the empowerment of subaltern castes, even as the deeper structures of brokerage, factionalism, and shifting party alliances continue to shape Bihar’s political landscape.

The RJD-led Mahagathbandhan continues to rely on the populism of caste majorities and identity politics; Chirag Paswan invokes new-age Dalit assertion and aspirational modernity; and Mukesh Sahani, the ‘son of Mallah’, mobilises smaller subaltern communities to negotiate a share in power. In contrast, Prashant Kishor’s Jan Suraaj movement embodies a new impatience with this system—seeking to replace brokerage with participatory, issue-based politics. Yet even his campaign’s micro-level outreach echoes the intimate social cartography that Maila Aanchal immortalised.

In essence, Bihar’s democracy still speaks in the idiom of Maryganj—a choreography of caste, charisma, and calculation. From the fading Nehruvian dream to the Mandal assertion, and from the Emergency to the present, Bihar’s story has been that of democracy’s messy magnificence: a dance of reversal, renewal, and resistance. The faces have changed, the rituals of democracy have become more digitised, yet elections remain as deeply rooted and relentless as democracy itself. No wonder, Renu’s Maila Aanchal remains not a memory, but a mirror of Bihar’s political present.

Ashwani Kumar is a poet and political scientist based in Mumbai. He is also the author of Community Warriors: State, Peasants, and Caste Armies in Bihar. Views are personal