“The Parsis came all the way from Persia, landing on the coast of Gujarat, not far from where I live—Nargol. The ruler, Jadi Rana, didn’t want foreigners in his land. He sent them a silver urn, filled to the brim with milk. The message was: our land is full. We have room for no more! … They added a pinch of sugar to the milk and sent it back! Their message? Just as the sugar has mingled with the milk, we shall mingle with you and add a dash of sweetness.”

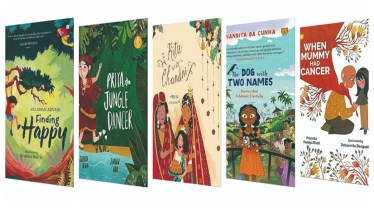

The classroom choruses “Awww” in unison, and for a moment, history softens into something else entirely—a parable of belonging, compassion, and coexistence. This is not a sermon from a teacher, but a story from Spoonful of Sugar, one of the tales in The Dog With Two Names by Mumbai-based author Nandita da Cunha.

Children’s books in India have long been anchored in the world of animals, rhymes and moral tales. But in recent years, a new crop of writers, illustrators, and editors has been steadily widening the scope—making space for grief, resilience, queerness, illness, and empathy. “It’s never too early to start,” Da Cunha says. “Stories are a safe space for children to question, to react, to put themselves in someone else’s shoes.”

Giggles to grief

“Just that moment, he saw a tree,

Filled with mangoes, it was meant to be!

He jumped up with joy and gobbled

a bunch,

Eating them happily, enjoying every munch!”

If Da Cunha’s stories weave empathy into everyday adventures, Gulshan Advani’s Finding Happy takes it inwards. Written during the pandemic, the book began as a “Covid-skill”, she recalls. Spending long months at home with her 13-year-old son led to conversations about what truly matters. “There are many books about what happiness looks like, but very few that talk about how to be happy in the everyday sense. Children don’t like preachy stuff, they want something goofy, interactive, and fun,” she says.

Her book encourages children to pause, notice small joys, and treat happiness as a journey rather than a destination. “Stories remain one of the most powerful ways to nurture empathy, happiness and resilience in kids, especially in today’s over-digitised world,” Advani adds.

That same instinct to fill a gap shaped When Mummy Had Cancer, by Priyanka Pandya Bhatt. The book is rooted in her own journey of illness. “My inspiration came from frustration, there was simply no literature for families navigating cancer,” she says. For her, cancer was not just about chemotherapy and scans but about emotions her family was forced to reckon with—fear, uncertainty, grief. “Children are more resilient than we think. They’re open to difficult conversations if we meet them at their level, factual, honest, but age-appropriate.”

Illustrator Debasmita Dasgupta translated that philosophy into tender visuals. “I used red as the colour of love, the root of empathy and connection while weaving in flowers and plants as reminders of resilience and healing,” she says. Her challenge was to capture the vulnerability of hair loss or loneliness without frightening young readers. “Sometimes emotions like fear or sadness are too complex for words, but children can feel them through a colour, a gesture, a detail. Art can hold them gently.”

Both author and illustrator insist that such stories are not about shielding children but equipping them. “Life is tough, but letting your children ride the storm with you shows them they’re valued members of the family,” Bhatt says. Writing the book, she admits, was also part of her own healing: “Each time I revisit the story, I confront my past but it’s slowly helping me let go.”

Weddings, jungles and editors’ desks

“Ritu didi was going to be the first bride in the Kapoor family to lead her own baraat…”

If grief and happiness form one end of the spectrum, joy, tradition and queerness form another. Bengaluru-based UX designer Ameya Narvankar is the author and illustrator of Ritu Weds Chandni, a picture book that centres on a lesbian wedding in small-town India. Born out of a project during his time at IIT Bombay, the book set out to address what he saw as a glaring absence in Indian children’s literature: queer representation.

“In India, weddings are the events children grow up seeing, so I thought, why not tell this story through the innocence of a child attending one?” he says. The protagonist, Ayesha, does not see Ritu and Chandni’s marriage as unusual. What unsettles her are the adults, neighbours who whisper, relatives who don’t turn up, passersby who sneer. Narvankar’s illustrations amplify this duality with metaphors—hurdles in the procession, blurb boxes shaped like knives carrying mean words, and moral brigades perched high on horses.

Publishers in India initially turned the book down, redirecting him towards “progressive” houses. Eventually, Yali Books in New York took it on, before Penguin Random House published it in India. “Children’s books are often a child’s first introduction to the outer world. Books like these validate identities, show different perspectives, or turn readers into allies,” Narvankar says.

Elsewhere, author Sathya Achia drew on her Kodava heritage to create Priya the Jungle Dancer. Raised in Canada, she spent childhood summers with her grandparents in Karnataka, and wanted to honour that bond. In the story, young Priya must master a traditional Kodava dance for school, but when her connection to her grandparents is interrupted, she must find her “inner jungle dancer.”

“I wanted to blend compassion, empathy, and courage,” says Achia. “Children are capable of understanding these emotions even in kindergarten, whether it’s loss, bullying, or resilience. The challenge is to tell them in an age-appropriate way.”

Illustrator Janan Abir, an early-years educator based in Dublin, saw the story as a chance to balance cultural authenticity with emotional depth. “Children need visuals to support their imagination. They should be able to feel what Priya feels,” she says. From jewellery to local houses, Abir was careful to embed cultural details that diaspora children could recognise. “I hope they spot the traditions, and also the resilience in Priya’s journey.”

Behind the scenes, editors shape how such themes make it to shelves. For The Dog With Two Names, editor Sudeshna Shome Ghosh immediately saw potential beyond a picture book. “When I first read The Three S, one of the stories, I thought this can’t be just a picture book. It had so much diversity, so many voices. That’s when I suggested a full collection,” she says.

For her, the appeal lay in the balance. “Nandita’s writing is never preachy. We wanted stories that could stand on their own, funny, sad, adventurous, but that also happened to carry empathy and diversity.” The market, she believes, is ripe. “There is a demand for such books, and more of them are getting written and published. If nicely done, they don’t overwhelm with the message, they’re just good stories.”

The publishing shift

“What if I forget my steps?” Priya asked nervously.

“All you need to remember is that you are a jungle dancer—fierce, grounded, and determined!” said Thatha.

Sohini Mitra, who heads the children’s programme at Penguin Random House India, sees this as part of a broader cultural and market shift. “Parents and educators are increasingly discerning about the content children are exposed to. They seek books that promote positive values and diverse perspectives, stories that give children food for thought,” she says. “It reflects broader societal changes and a growing recognition of the importance of emotional intelligence in early development.”

The challenge, she adds, is balance. “It’s truly a writer’s craft that makes a story shine. Even if there’s a deeper message, the story must always lead. Children engage with tales that are timeless and strike a chord.”

Mitra sees this wave as global, but with distinct Indian resonances. “What sets Indian children’s publishing apart is its rich tapestry of languages, regional narratives, and cultural nuances. Books often blend contemporary social issues with local contexts, addressing caste, gender issues, religion, disability, and family dynamics in ways that resonate deeply with the Indian reader.”

Publishers are listening. Tina Narang, executive publisher at HarperCollins Children’s Books India, notes that the industry has begun to embrace difficult and sensitive topics. “It’s definitely a perceptible shift that has become more pronounced over the last couple of years. Children today are leading wildly challenging lives, and stories that stress on the importance of empathy, kindness and emotional well-being are not just important, they are necessary,” she says.

Why empathy now?

“Mummy’s hair started to fall out. She was so brave, she asked Daddy to shave her hair off. This made Mummy sad. I gave her a big hug and a kiss and that made her feel better.”

The shift towards emotional storytelling in children’s books mirrors larger social anxieties, about fractured communities, rising intolerance, and the isolating force of digital media. “Kids get stories through gaming and YouTube,” Da Cunha points out, “but books make them feel the story. Nothing beats imagining a character in your own way.”

Many argue that children today are navigating more complex social realities earlier than previous generations— bullying amplified by social media, blended families, exposure to illness, climate anxiety. Stories that normalise empathy and resilience are not indulgences but necessities.

Dr Radhika Gad, clinical psychologist, Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani Hospital, Mumbai, says introducing a conversation around emotions and empathy at an early age through the help of examples and modelling behaviour, helps the child express them better.

“Children as young as one or two can recognise basic emotions like happiness, sadness, or anger. They notice emotional shifts in caregivers through tone and expression and react accordingly. Emotional intelligence grows with age, experiences, and vocabulary. That’s why introducing conversations around emotions early through examples, modelling, and books is so powerful.”

She adds that age-appropriate books packed with relatable examples allow children to recognise emotions, explore healthy ways of expressing them, and understand their consequences. “Young children are curious and observant and learn a lot through observation. Books that focus on empathy and inclusivity helps the child peek into a world beyond their neighbourhood and gain knowledge about different identities and cultures. They help cultivate empathy and appropriate emotional responses. They also help normalise the expression of emotionally charged material and build tolerance and compassion towards others,” says Dr Gad.

Narang agrees. “It’s vital to acknowledge that kids today are smarter and more perceptive than we may sometimes expect them to be, and that they don’t like to be talked down to. It’s essential then that we expose them early to difficult ideas and concepts like empathy, mental health and resilience, as long as we are careful in the way the idea is being presented, and how the story is being told.”

The common thread is subtlety. None of these authors and illustrators want to write moral textbooks. They want to tell stories children will laugh at, cry with, or carry in their pockets, stories that can gently expand their emotional world.

As Sudeshna Shome Ghosh puts it: “If the story works on its own, the empathy follows naturally.”