By Reena Singh

The ocean has been here for billions of years. It has seen mass extinctions, ice ages, and the rise of civilisations. Yet in David Attenborough’s Ocean: Earth’s Last Wilderness, the sea is not presented as an immovable constant but as a living, fragile and complex system. David Attenborough, with his characteristic warmth and authority, invites us beneath the surface of our planet’s largest and least understood realm. More than two-thirds of Earth is cloaked in water, yet we have explored only a fraction of it.

The structure of the book mirrors the descent of a diver. We begin in the shallow, sunlit waters where coral reefs are described as “the most dazzling array of life anywhere in the world’s ocean”. These reefs, like bustling underwater cities, pulse with colour and energy. From there, he guides us into the diverse kelp forests, the deeper twilight zones where sunlight fades and bioluminescent creatures glimmer like stars, and finally into the crushing depths where few creatures survive.

Calling the ocean “Earth’s last wilderness” is not merely poetic flourish but, as Attenborough insists, a statement of fact. While forests are felled and mountains mined, the ocean still holds vast stretches untouched by humans. Yet even this refuge is no longer secure. Overfishing, pollution, and climate change form shadows that stretch across the coral gardens and kelp forests. The damage is undeniable, and it is accelerating. Attenborough doesn’t sensationalise these threats; he presents them with clarity, backed by decades of observation and scientific insight.

Survival in the ocean is often brutal, shaped by predation, scarcity, and extinction. Attenborough underscores how fragile and interdependent these ecosystems are, in which every part, from plankton to whale, is connected. He reminds us that the ocean is not just a victim but also a healer. It absorbs carbon, regulates climate, and sustains life in ways we are only beginning to understand. But it can only perform these functions if humanity stops treating it as a dumping ground and begins to see it as a partner.

Attenborough points to marine protected areas that have rebounded with surprising speed, communities that have embraced sustainable fishing practices, and growing global cooperation as signs that recovery is possible. He also recalls how conservation efforts once saved the blue whale from the brink of extinction which is a reminder that change is possible when action is taken. It’s not just about governments or corporations but about all of us. The choices we make, the products we buy, and the stories we tell—everything has an impact.

Protecting marine life is not an abstract idea but a practical necessity for planetary health. The ocean has endured for millennia, adapting and evolving through time. But resilience has its limits. You don’t finish this book wanting to conquer the sea. You finish it wanting to protect it, because to protect the ocean is to protect ourselves. In terms of audience, the text strikes a balance between scientific content and literary expression, making it suitable for a broad readership. Whether you’re a marine biologist, a student, or simply someone who’s stood at the shore and wondered what lies beneath, Ocean: Earth’s Last Wilderness offers insight, reflection, and a call to action. It’s a reminder that the ocean is not just out there but it’s part of us. And its future depends on what we choose to do next.

Reena Singh is senior fellow, ICRIER (Views expressed are personal)

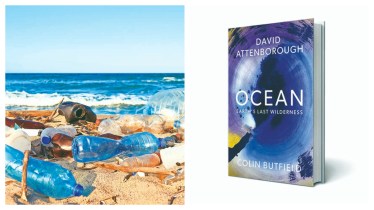

Ocean: Earth’s Last Wilderness

David Attenborough & Colin Butfield

Hachette

Pp 400, Rs 1,299