“A sixth of Humanity’ is not light reading—far from it, but for those willing to engage with its depth, it offers rich reward by being rigorous, wide-ranging and insightful. It may be less comfortable for readers looking for a simple narrative, but for anyone seeking to understand “why India is the way it is” and “where it might be going”, this is essential reading.

The book is an audacious attempt to trace how India—uniquely and daringly—attempted four concurrent transformations—building a state, creating an economy, changing society, and forging a sense of nationhood under conditions of universal suffrage. Few books attempt such a grand sweep of India’s development history while integrating politics, economics, and social change. The joint authorship by Devesh Kapur, one of India’s most respected political scientists, and Arvind Subramanian, one of its best-known economists, adds to the book’s strength as it includes insights from politics, economics, history, and literature and provides a developmental history of India that is big, bold, engaging, and unique.

The authors argue that India’s path has been distinctively ‘precocious’ in comparative terms: democracy before development; high-skilled services before low-skilled manufacturing, and globalisation that sent talented people abroad while many at home were left behind. This encapsulates a central framing of the book: that India’s development path was unusual (and perhaps unorthodox) in which multiple transformations (state, economy, society, nation) were attempted simultaneously, often out of sequence compared to other countries. Even as India has achieved impressive milestones (digital infrastructure, electoral democracy, global presence), the book underscores enduring contradictions: inequality, regional disparities, under-provision of public goods, and fragility of institutions.

The authors also show that some of the conventional ‘either-or’ dichotomies (like growth vs equity, politics vs economics) are too simplistic. For example, they argue how India’s ‘best time’ could be seen as combining thinkers like Jagdish Bhagwati and Amartya Sen rather than framing them in opposition. This is a refreshing take on one of the most watched ‘either-or’ syndrome in India’s economic thinking. For context, the debate between the two great economists centres on whether economic growth or social development should be prioritised. Bhagwati has argued for prioritising economic growth through policies like liberalisation, believing that increased wealth will naturally fund social programmes later (trickle-down effect). In contrast, Sen emphasises investing in human capital through health and education first, as he believes this is necessary to create a dynamic workforce and achieve sustainable growth.

A vivid articulation of one of the book’s core themes is the nature of the Indian state and its role in development and society. For example, the book says, India’s default ideology is statism, best understood in its Indian rendition—‘mai-baap sarkar’ or ‘mai-baapism’. This is more than the narrow ideology of the Left, with its belief in state-driven industrialisation or welfarism. It is more all-encompassing and shared well beyond the narrow elite, a sort of mass ideology that includes the Right as much as the Left. It connotes the State as provider and protector, refuge and comfort, even as it has also been the apathetic parent, absentee landlord, tormentor and a Wizard of Oz-like figure, projecting an illusion of power sans its reality. The Indian ecosphere is almost universally mai-baapist.

While aspects of mai-baapism were motivated by a sort of elite paternalism, a central feature has been a deep-rooted control mentality. By making the State the locus of all change, it disincentivised other forms of societal collective action. The centrality of mai-baapism was beset by several paradoxes. Even as the State was severely critiqued for its failings, the first solution to any problem was inevitably to ask it to do more. There was no attempt to distinguish between what was essential for the nation and what was desirable.

The authors also view failure of the State as not just structural but tightly bound up with agency, historical endowments and chance. The reference to Punjab/Haryana in a chapter on ‘India’s Indias’ illustrates their argument that even promising growth trajectories can unravel. Read on: “All the major failures in India are primarily, and self-evidently, due to a failure of agency—the sum of policy actions and inactions taken by those in charge. They happened due to some distinctive interplay between these agency failures, legacy (historical/geographical) and contingency. The rapid growth between 1960 and 1980 was experienced most by Haryana and Punjab, a testament to the Green Revolution.”

The Congress, as Mahatma Gandhi acknowledged, was supported by the landed elite, “which created a silent debt”, the book says. At another place it draws a distinction between India’s present-day strategy of promoting national champions and South Korean Chaebols, the latter serving national interest more effectively than the former. There isn’t any doubt that most of India’s policy choices have been elite-driven, not responses to bottom-up pressures. In the process, Indian democracy revealed itself to be an “equal-opportunity vested-interest creator and sustainer”. That’s a stinging comment but quite accurate.

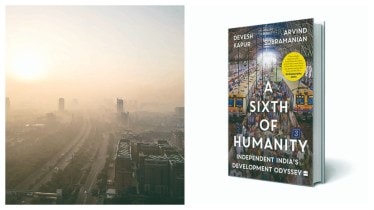

The book does well by not producing a laundry list of critical reforms to address future challenges as these are well-documented already. Instead, it has asked a more pertinent question: if India can’t even solve the pollution problem that manifestly and acutely affects 33 million citizens in its capital city, the prospects for solving the larger challenges confronting the country remain slim.

Overall, A Sixth of Humanity gives a strong retrospective and analysis of India’s transformation. But a stronger emphasis on what the future holds (and how to address the remaining structural issues) might have enhanced the utility. Also, while attempting multi-dimensional coverage, certain chapters lean more heavily toward the economic or policy side, and less on lived social change or cultural dimensions.

A Sixth of Humanity: Independent India’s Development Odyssey

Devesh Kapur & Arvind Subramanian

HarperCollins

Pp 760, Rs 1,299