The Kochi-Muziris Biennale (KMB) is back to where it started ten years ago. In December 2012, the then Oommen Chandy-led Kerala government decided to let India’s first biennale take off and launch a parallel vigilance inquiry into alleged financial irregularities in its organisation, marking a new chapter in the history of Indian art. A decade later, the artists invited by the biennale to participate in its new edition are those demanding answers to the manner in which it is run.

The fifth edition of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale was scheduled to begin on December 12, 2020 when the Covid-19 health emergency forced its postponement. An unrelenting pandemic (the first coronavirus case in Indian was reported in a medical student from Kerala returning from Wuhan, the epicentre of the pandemic in China), kept the biennale shut for another two years, wiping out completely the duration of a single edition.

The fifth edition’s curator, the Indian-Singaporean artist Shubigi Rao, had wrapped up the selection of artists after travelling around the world when Covid-19 came and upset the plans. The selection was shuffled again, with many dropping out and many more added, for a December 2022 opening. The pandemic had ebbed and travellers were up in the air. What happened next was not part of Rao or the Kochi Biennale Foundation’s plans.

Faulty start

A day before the scheduled opening, the biennale foundation that runs the event announced that the biennale wouldn’t be opened to the public on December 12 while allowing the satellite exhibitions to proceed as planned. A new date, December 23, was offered as the new date of opening. Some satellite exhibitions, too, followed the biennale in postponing their own opening.

Curiously, the biennale foundation didn’t abandon the formal inauguration of the partly public-funded event by Kerala chief minister Pinarayi Vijayan on December 12 in the presence of several state ministers and even an ambassador. Rao and many participating artists were not present. A scheduled Theyyam performance and dinner party were cancelled. The artists had their own party at a rooftop bistro, paying from their pockets and playing foosball. Rao attended this time.

Several factors contributed to the unprecedented postponement of the biennale. The main reason attributed by the biennale foundation was the Aspinwall House venue, where the majority of works are exhibited, wasn’t ready. The Aspinwall House, a major part of which is owned by a private builder, wasn’t completely available to the biennale until two weeks before December 12. An unseasonal rain in many parts of Kerala, including Fort Kochi, had also slowed down the progress of the work at the venues spread across the heritage town. Many artists weren’t happy at the pace their works were being mounted on the sites. The biennale, which had become a fixture on several national and international calendars of must-see events, was now suddenly looking like a disaster-hit destination.

Travel schedules were upset and several participants and visitors left Fort Kochi soon. The biennale foundation worked overtime in the next few days to get the event back on the rails, finally hoisting its flag over the Aspinwall House on December 23. But it will have to answer several questions, including those raised by the artists themselves in an open letter (see side story), mainly why the foundation didn’t foresee that the venues won’t be ready in time. While the biennale has struggled in every edition to present the country’s biggest contemporary art event to the public on a date (twelfth day of twelfth month) it has been obsessed with, this time the questions are not going away too soon.

Biennale begins

On December 23, the biennale opened its venues to the public, returning art to the centrestage. Themed In Our Veins Flow Ink and Fire, the current edition has 90 artists from India and abroad responding to the state of the world. “This edition of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale embodies the joy of experiencing practices of divergent sensibilities, under conditions both joyful and grim,” says Rao in her curatorial note referring to the disastrous effects of the pandemic. “There is optimism even in the darkest absurdity… It is in the robustness of humour that we can imagine the possibility of sustained kinship, and remember that we are not isolated in this fight.”

Among the works is Ukrainian artist Zhanna Kadyrova’s Palianytsia (a circular Ukrainian bread), an installation of sliced rocks set on a table for a meal to represent Ukrainian hospitality. The Kyiv-based Kadyrova, who fled to the west of Ukraine after the Russian invasion, uses her art to raise emergency funds for her country. The biennale has artists from Myanmar, including Rita Khin, whose Soulless City portrays the new capital built by the military regime through a series of photographs, and Yu Yu Myint Than, whose works are portraits of protesters who hit the streets following the military coup against the democratically-elected government.

Indonesian-origin artist Nathalie Muchamad revisits the origins of Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) in the 1955 Bandung conference in Indonesia. Taking the help of the traditional Javanese Batik textile technique, Muchamad, affirms her identity as an Indonesian woman born in New Caledonia, where her ancestors arrived as slave labour for the new coffee plantations. “I am born from diversity. I think uniformation is a form of violence,” says the artist, who lives in the French territory, Mayotte, an Indian Ocean island off the coast of Africa. “My work is a homage to my ancestors. I use Batik to tell stories from the past and affirm that I am from three cultures.”

Retelling stories

Filipino artist Pio Abad and British designer Frances Wadsworth Jones reconstruct the Romanov tiara, part of the jewellery collection of Imelda Marcos, as a witness to political upheavals, especially in the former Soviet Union and the Philippines, in their work, Second-hand Time. “We narrate history through beautiful objects,” says Abad, whose ten-year project on the Imelda Marcos jewellery collection also includes the famed Pink Diamond from the Golconda mines.

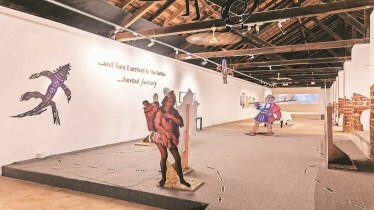

Colectivo Ayllu, a community of sexually and gender diverse artists, activists and historians of colour from South America, living and working in Spain, use their installation, Indian Fantasies: Species and Spices, to retell stories of indigenous people suppressed by the European settlers after the discovery of the Americas by the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus, who had originally set sail to find a new route to India. “We are dealing with pain, memories and misunderstandings,” says Ecuadorian anthropologist and Colectivo Ayllu member Kimi Rojas. “The fantasy of Columbus was that he will find a fastest way to go to India to buy spices,” adds Rojas, who reiterates the respect for diverse sexuality and freedom among the indigenous communities in South America. “Today, we are fighting not for our rights, but the survival of our sexuality that existed with our ancestors.”

Indian artists participating in the biennale this year include Vivan Sundaram, who is making a return after showing his installation, Black Gold, at the first edition in 2012; Amar Kanwar, another returning artist whose work at the Anand Warehouse venue this time, Such a Morning (2017), is on the human predicament today; visual artist Shreya Shukla’s The Captives about the body and material using images and text; Goan artist Sahil Naik’s installation, All is water and to water must we return, on the submergence of a village in his home state 50 years ago to build a dam; and Kerala artist E N Santhi’s paintings of sacred groves and shrines called Ka¯vû that she was forbidden from visiting as a child.

The biennale runs up to April 10.

Shock & concern

On December 23, the day of the delayed opening of the fifth edition of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale (KMB) to the public, over 50 participating artists published an open letter listing concerns and seeking changes. Expressing “shock” and “concern” at the way the Biennale has unfolded this year, the artists said the experiences of the invited artists from this year and past editions offer an opportunity to “radically transform the KMB as an event and institution—changes that are clearly, urgently needed”.

The letter said the artists were “overwhelmed by many problems” such as shipments delayed in transit and at customs past the opening day, rain leaking into all the exhibition spaces impacting equipment and artworks, a lack of steady electrical power, shortage of equipment and insufficient workforce on all production teams. Artists, it said, were drawn into daily struggles with the biennale management, “whose organisational shortcomings and lack of transparency had made a timely and graceful opening impossible long before it was postponed”.

The letter said the considerable challenges that participating artists would encounter upon arrival were never communicated and “none of us could make an informed decision as to whether to travel to Kochi or indeed to even participate under the circumstances”. “While artists produced projects in good faith, our commitment to the Biennale was not reciprocated, and responsibility for the many problems that surrounded it, evaded. The day before the scheduled opening, less than ten percent of the exhibition was ready,” it added.

Also read: 3 cocktails to warm up with this cold-weather season

“We believe the Biennale Foundation should have made the decision to postpone weeks earlier, when many of the failures were already apparent—well before thousands of art-lovers travelled for the opening days, and most artists themselves had to return and could not stay on to see their own work installed or engage with the work of fellow artists and visitors,” the letter said.

Analysing their experiences, the artists said “the way the KMB (Kochi-Muziris Biennale) is currently organised hinders the artistic process, and closes opportunities for artists rather than enabling them”. The issues are “organisational and systemic”, it said while summarising how “so many things have gone wrong”.