By Kunal Doley

Manipur nathaki jabo (There won’t be a Manipur),” says the former deputy chief of NSCN-IM—the largest of the several factions of Naga rebels—as he responds to a query by the author about what could possibly happen if a political understanding isn’t reached about securing the Naga ‘homelands’ in the northeast state of Manipur. The former ‘major general’ was referring to the demand for ‘administrative autonomy’ and how the state would ‘break’ if the government in Manipur, which is home to several Naga tribes living across more than a third of its territory, didn’t agree to it.

The rebel leader’s observation is not an idle one. Northeast India accounts for nearly a seventh of the country’s landmass and is home to nearly 50 million people. It is a gateway to immense possibilities, from hydrocarbons to regional trade, and a bulwark of the country’s security in the shadow of China. The region is also home to immense ethnic and communal tension, and an ongoing Naga conflict that is shrouded in a cloud of uncertainty. No wonder the author writes: “India’s eastern elixir is a seductive, stunningly complex cocktail.”

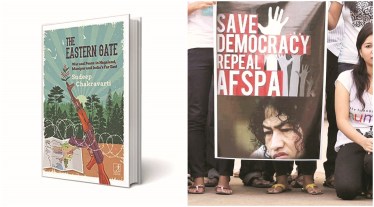

In The Eastern Gate: War and Peace in Nagaland, Manipur and India’s Far East, Sudeep Chakravarti—a keen observer and a frequent chronicler of northeast India— discusses in detail the “issues that snarl community relationships in Manipur, and the massive umbilical of the Naga question that is irrevocably tied to this state and irrevocably affects the region”.

The author, however, prefers to call northeast India ‘Far-Eastern India’. He feels there cannot be a Look- or Act East Policy by overlooking the region. “India’s relations with this region will mark the country’s engagement with its northern and eastern neighbours—China, Bangladesh, Nepal, Myanmar and Bhutan. Equally, there can be no doubt whatsoever that India’s relations with these neighbours will have a direct bearing on how this region thrives, or falls by the wayside, in the future,” he writes.

This is also the region that nurtures legislations like the Armed Forces (Special) Powers Act (AFSPA), 1958, that permits the Indian security apparatus to hurt and kill citizens with impunity. There was a renewed debate over the controversial Act when 14 innocent villagers were killed by the security forces in Nagaland’s Mon district in December last year.

The Eastern Gate takes off from where Highway 39: Journeys Through a Fractured Land ends. Highway 39 (originally published in 2012) was Chakravarti’s previous attempt at unravelling the brutal history of Nagaland and Manipur, and their violent and restive present. The award-winning author is also behind several best-selling works of history, ethnography, politics, and conflict resolution, including Plassey: The Battle that Changed the Course of Indian History and The Bengalis: A Portrait of a Community, among others.

For this book, however, Chakravarti adds a ‘dispatches’ approach to include news breaks as they happened, information and messages that he received and exchanged from and with his sources, government officials and rebel leaders, preparatory notes and thoughts, snippets from his travel diaries, etc.

The author’s narrative begins from around the middle of 2014 when the first BJP-led government of PM Narendra Modi was just weeks away from winning the general elections. He then touches upon some of the key events that took place in the region, like the Framework Agreement signed in New Delhi between the central government and the NSCN-IM in 2015 that would formally end conflict and pave the way for an uneasy ceasefire.

The author writes about the hill people-versus-plain people conflict of Manipur that has its roots in a legislation dating back to the early 1960s, as also the ‘Alternative Arrangement’, a demand that has been made by several Naga tribes under the umbrella of the United Naga Council for Naga homelands to be delinked from the administrative ambit of the Manipur government.

To underline the root causes of the latter-day conflicts over homelands, Chakravarti goes back to a bit of history and writes about the British colonial government and its approach in dealing with the Nagas at the time. Coming back to the present, he talks about some of the major developments that took place in northeast India in the later part of 2010s, like civil rights activist Irom Sharmila breaking her 16-year-long fast that she had undertaken to protest against the draconian AFSPA; CM N Biren Singh’s rise to power ending the three-term run of O Ibobi Singh of the Congress in Manipur; the killing of Arunachal Pradesh legislator Tirong Aboh allegedly by NSCN-IM rebels in 2019, and the release of Rajkumar Meghen, the former chairman of UNLF, from jail, among others.

The author also dwells on the Kuki community and its history and aspiration in the book. It talks about the 1990s when the NSCN-IM led a military-style campaign to oust the tribe from what it perceived as its territory and the retaliatory spiral of violence that killed over a thousand people on both sides. According to the Nagas, all the land in the hills actually belong to them and the Kukis were ‘vagabonds’ who came and settled there. The Meiteis feel the entire state belongs to them—it was a part of their old kingdom. So, unless this major issue of land or territory gets resolved, we are not going to head anywhere, an Intelligence Bureau official puts in the book.

The author, however, goes on to add that there are dozens beyond Meitei-Naga-Kuki to other ethnicities, tribal sub-groups and clans, religious schisms, those affected by depredations of the state. “In Northeast India, there will need to be years of patience and healing to deal with decades of hurt and horror,” he writes.

As a conclusion, the author gives a wishful thought for a headline—something that he would dearly love to see for Nagaland, Manipur, and all of far-eastern India, in the near future—“Peace Breaks Out”. Sometimes hope is all we have.

The Eastern Gate: War and Peace in Nagaland, Manipur and India’s Far East

Sudeep Chakravarti

Simon & Schuster

Pp 432, Rs 899