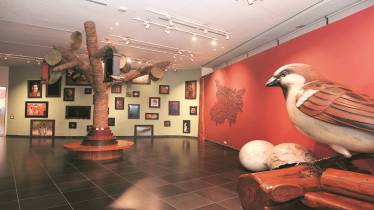

Walk into the Children’s Gallery at Bihar Museum in Patna, and the first thing that strikes you is the section on flora and fauna. For a moment, you may think you are inside a forest—complete with caves, trees, birds and animals. A mighty king cobra rests over a rock. You can see a mango tree with a monkey swinging through it. There’s a flying fox, deer, gray francolin, alligator, turtle, krait, night jar and several other lesser-known flora and fauna. On one corner, there stands a rhinoceros.

You can move through the caves and climb atop a ‘cliff’, where binoculars are in place for a wildlife-watching experience.

While many people associate museums with just ancient antiquities, the Children’s Gallery at Bihar Museum comes as a breath of fresh air. The idea is to generate ample engagement and stoke inquisitiveness among children while not dumbing down the exhibits. The resting king cobra, for instance, comes with a message, in both English and Hindi: “The king cobra can grow up to 18 feet long—nearly the length of two cars.” This is to make it informative and palatable for children across ages. Along with it is mentioned the status of the animal, which is “vulnerable”.

“We are trying to give a message that all these flora and fauna are endangered, and it is our duty to protect them,” says Swati Singh, curatorial associate at the Bihar Museum, who offers guided tours through the Children’s Gallery. Commenting on the exhibit on rhinoceros, Singh says: “You see, the rhinoceros is not from our state but from neighbouring Assam.”

Merging wildlife and literature is the installation of Panchatantra, where you can read or listen to the collection of the celebrated ancient fable.

No wonder, you often get to hear things inside the museum like: “This is something they should include in the school curriculum. There is just so much here.”

The extensive use of tech add-ons, puzzles and games, too, enhances both engagement and experience. For example, solving a puzzle by Chanakya allows you to sit on the ‘Maurya Throne’, which makes for an interesting photograph. This is in the ‘Maurya’ section, a crucial aspect of Bihar’s rich history. Here, emphasis is as much on the royalty as on the religious influence, with an extensive use of Toran gates, an intrinsic aspect of the Buddhist stupas. A close glance exposes the intrinsic carvings done on the replicas. However, unlike in history galleries, in the Children’s Gallery, you are allowed to touch anything, play around, and use the five senses.

Another interesting section is the discovery room, which gives children a glimpse into the world of archaeology. “It gives kids an idea who archaeologists are, what they do, what tools they use, etc,” explains Singh. “We get children from various backgrounds. While some come from urban, affluent backgrounds, there are also those from villages who find it difficult to understand English. What helps here to break the ice is communicating with them in Bhojpuri, if the kids are from the Bhojpur region of Bihar,” Singh explains.

Interestingly, adults can be seen engaged in the gallery as much as the children. “Initially, adults are generally hesitant to visit the Children’s Gallery, but they have to, given their children. But once they step inside, they are stuck with the adventurous things their children are enjoying. After a while, they start enjoying themselves,” the curator says.

Designed for children, the gallery also hosts college students and even IAS trainees. “NIFT (National Institute of Fashion Technology) students are our regular visitors,” says Singh, adding, “IAS trainees also come here. We take them around the Children’s Gallery and discuss why this section is important.”

Museums, both in India and abroad, are undergoing a change from being static spaces to becoming dynamic centres to learn, play and engage in art, culture and heritage. “Earlier, slightly older people would visit museums. Now, younger people and children are visiting. For example, the Bihar Museum has a strong Children’s Gallery, one of the very few in the country. There is so much interactivity, puzzles, pictures and engagement,” says Alka Pande, an art historian and museum curator.

On the idea behind coming up with an exclusive section for children, Anjani Kumar Singh, the director-general of the Bihar Museum, comments, “Currently, Bihar and eastern Uttar Pradesh have the most youthful population in India. About 50% of Bihar’s population is aged 25 years and less. They are the future. They have talent, but what they need is training, and a museum can play a role here.”

“It instills curiosity in children. They become more curious to know about museums,” says Singh. “Earlier, they would think museums are just about broken, ancient antiquities. But in the Children’s Gallery, I tell them not to come with this preconceived notion. Rather, think about why these broken, ancient antiquities are so important that they have been preserved in such a way,” she adds.

Immersive experience

Let’s now move from east to west India. In 2019, the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS) in Mumbai launched a Children’s Museum, a first for the city. Here, too, the emphasis is on designing an experience that engages all five senses, making for an immersive experience for children.

“Museums designed for children usually address a particular interest. They often consist of collections of toys or focus on areas like science and technology. Rather than populating the Children’s Museum with ‘things’ that we feel would interest children, the method is more crucial, and populating the museum with ideas that children want to engage with is key,” says Vaidehi Savnal, curator, education and public programmes at the CSMVS.

For example, the museum houses a wonderful set of handling collections where children can touch and feel objects, a deviation from the ‘Don’t Touch’ rule at museums. To stoke interest in archaeology is the archaeology exploration pit, where children can participate in a mock excavation, digging and discovering objects. “We have a large green area that is home to several rare species of plants. We have created a tree trail around the campus that children can discover at the centre of which is a 100-year-old Baobab tree. A 100-seater amphitheatre has enabled us to host music, dance, theatre and literature events, not only curated for children but also featuring budding young artistes,” Savnal says. Apart from that, festivals and programmes are conducted on weekends for children to engage with art, craft, languages and the performing arts.

The importance of such an experience is understandable. While adults have several avenues to engage with art, culture and heritage, children have limited options. “The Children’s Museum gives the young the much-needed access to cultural recreation,” the curator says. Here, accepting and building upon the fact that children have complex minds and sound intellect is crucial, too.

On this, Savnal says, “We recently opened an exhibition curated by children for children called POV: Points of View. Over the course of the summer, 14 children picked five objects each and wrote their own unique interpretation about it. As adults, we grossly underestimate a child’s ability to think deeply and look critically at the world around them. They are opinionated and have such a refreshing take on things. Here is what one of the children, a 14-year-old, wrote about a decorative pot from our collection: ‘The museum has a collection of beautifully decorated water pots with intricate carvings on the surface. Some of these have carvings of animals on the sides of the pots suggesting that they may have had ritual use. However, the ornate exterior of the pot is useless without the void in the middle and the void is useless without the walls showing how solids and voids are both necessary.’ This is such an incredibly nuanced way of looking at an object, none of us would have thought to look at it in that sense.”

And if done right, children get engaged. For example, according to Savnal, since its inception, the Children’s Museum has worked with over 10 lakh children. “During the academic year, we usually receive large school groups on weekdays, sometimes over 500 children per day. Weekends see a lot of family audiences coming in to spend a day together. Vacation times see a lot of families and tourists from around the country coming in,” she says. Not just that, 30% of the museum’s total number of visitors are children, she adds.

Growing interest

While a growing interest can be seen in museums for children, the concept is not new in India. Take, for instance, the Nehru Children’s Museum, which opened in Kolkata in 1972. Spread across four floors, the museum houses a Doll Gallery, “where children can see dolls from 88 countries in fashionable dresses. With this, a fair knowledge of the dress and appearance of the people from different countries is instilled in their mind of the children and other visitors who have least idea on globalisation,” the museum’s website says. There is also a Ramayana Gallery and those for Mahabharata and Ganesha.

There is also the National Children Museum in Delhi. It houses “a rich collection of objects that fascinates children including toys and dolls from different countries, stone and bronze objects, traditional jewellery, utensils, art, and craft material, musical instruments, head gears, currency of various countries, etc,” its website says.

However, the shift from children’s museums being static spaces to dynamic ones is evident. Coming up soon in Mumbai is the Museum of Solutions, or MuSo, a JSW initiative. Through its activities and galleries, it aims to be a platform for children to engage in problem-solving and creating a positive impact on the world. “For more than a decade, I’ve held on to the belief that learning should be meaningful and fun for all children and so when I dreamt of MuSo, I dreamt of a space where children were inspired, enabled and empowered to make meaningful change in the world, together, today,” says Tanvi Jindal Shete, founder and CEO, Museum of Solutions. “MuSo is a bold vision backed by the courage and belief that children don’t need to become adults to be changemakers,” she adds, as per MuSo’s booklet.

The museum houses an amphitheatre for community performances, music, theatre, comedy and film. The Art Gallery is “a space for creatives to display their inspiring work and individuals to immerse themselves in a world of art,” as per MuSo’s booklet. The Precious Plastic section will enable children to learn about different types of plastic waste and how to recycle it. Then, there is the Library of Solutions, a reading room with an “inclusive collection” of books.

“Join us for book writing workshops, book readings, and book clubs designed just for children,” it says. One can discover the world of STEAM, not STEM, with the additional “A” standing for “Art” at the Play Lab. On the other hand, the Make Lab is where visitors can unleash their “imagination through art, technology, woodworking, photography, electronics and more by creating your own masterpieces and collaborating with your teammates”. An important element is the Grow Lab, where you can “explore sustainable practices with nature as your teacher”. Here, you can learn about the food cycle, sow seeds, watch plants grow and take part in workshops and activities that promote sustainability and clean living.

Digital disruption

A one-of-its-kind ‘museum’ established by 13-year-old Krish Nawal and 16-year-old Manya Roongta is the Children’s Art Museum of India (CAMI). A digital platform, it offers a “space for children to express themselves through art and creativity”.

“Our platform emerged to address a significant gap in the art world. While numerous platforms focused on art instruction, there was a dearth of platforms to showcase the work of young artists. Additionally, young artists struggled to connect and learn from their peers. Our platform fills these voids by providing a space for young artists to exhibit their creations and foster a supportive community,” says Krish.

However, when you think of a museum, antiquities and a physical space come to mind, both of which are largely absent at CAMI. On this, the founder says, “Virtual art galleries like ours function as modern mediums of expression by providing a digital platform for young artists to showcase their creations to a global audience. Through interactive exhibits and virtual displays, these galleries transcend physical limitations, allowing artists to share their work, connect with others, and express themselves creatively in a digital space that is accessible, inclusive and inspiring. Moreover, an online space was chosen for the CAMI to ensure accessibility and reach a wider audience seating, both in rural and urban areas of India.”

This clearly reflects a reimagining of the very idea of museums, away from physical, static spaces to dynamic, technically-aided ones. And museums for children are both stoking that change and embracing it.