By Faizal Khan

In the middle of the violence during the Partition, Krishen Khanna would seek peace in the comforting words of a Sikh waiter in Shimla where his family had fled after being uprooted from Lahore. Khanna, only 22 at that time, walked with the waiter often to his hotel, listening intently to the working man’s approach to a hard life’s travails. For several decades to come, the struggle of the worker would form a substantial part of his art practice that probed the ills of inequalities in the midst of unparalleled wealth and privilege.

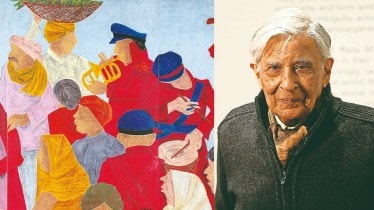

Khanna, one of the most influential modernist painters in the history of Indian art who turned 100 on July 5, amassed a series of works in his long and prolific career spanning eight decades that pays tribute to the working class. There have been images of tailors, tea sellers and truck drivers recurring in his paintings, revealing the paradox of wealth and poverty existing side by side. Standing out for their haunting appeal towards humaneness and understanding have been his increasingly abundant depiction of the bandwallas, the invisible individuals who provided the lofty soundtrack for celebration.

Palette and pain

The striking images of the bandwallas roar out of his canvases, sometimes several feet long in simultaneous panels. The colourfully attired street musicians are faceless with the artist leaving a blank inside the contours of the faces, adding agency to their forgetful contribution to a celebration. Khanna’s brush strokes, however, make their presence pronounced in the loud tones of each musician’s colourful dresses, hats, drums, drumsticks and trumpets. The bandwallas are almost always surrounded by more faceless, ordinary people exacerbating the divide.

The bandwallas’ theme is the choice for an exhibition of Krishen Khanna’s paintings at the Saffronart Gallery at The Oberoi in the national capital, titled Krishen Khanna at 100, Legacy of a Modern Master. Organised from July 7 to 19, the exhibition, which follows the publication of My 100th Year, a book celebrating the life and works of Khanna, brings together works underlining the artist’s emphasis on humanity.

“Undeniably one of India’s greatest living modern artists, Krishen Khanna has built a practice that not only reflects his deep humanity, but is also a vital chronicle of the social and cultural fabric of post-Independence India,” says Dinesh Vazirani, Saffronart CEO and co-founder. “His work resonates with lyricism, depth, and an unwavering sincerity, shaped by a rare gift for observing his subjects keenly and with great empathy,” he adds.

“Bandwallas first appeared in Krishen Khanna’s oeuvre in the 1970s. He happened to witness a wedding procession, and the sight of the musicians in red, with their instruments, left a significant impression on him,” explains Punya Nagpal, senior vice president, Saffronart. “It is a subject he has returned to in his work for many decades, and even at the age of 100, he continues to do so. It has become almost like his hallmark-much like horses were for MF Husain,” adds Nagpal.

Balm for bandwallas

The astonishing brevity of objects and surroundings in his works seen in his series of paintings on bandwallas, chaiwallas and truckwallas, like the mere presence of a table or a a street dog, profoundly captures the unseen struggle and suffering of the working class. The stark portrayal of the unseen wealth of labour by Khanna, who lives in Gurugram, Haryana, owes its origins to the woes of the Partition he personally witnessed as a young man fleeing his hometown of Lahore, now in Pakistan, with virtually nothing. That uncertainty of life would go on to influence his art practice, long after his initial years as a banker in Mumbai in the 1950s, a period that saw him build a lasting friendship with fellow artists like MF Husain, FN Souza, SH Raza, Akbar Padamsee, Tyeb Mehta, VS Gaitonde and Ram Kumar, all members of the Progressive Artists’ Group, founded in 1947.

“The market responds very well to Krishen Khanna’s bandwallas’ works. They are popular, typically featuring a bright and colourful palette. While the works may appear celebratory, for the bandwallas, this is simply his job—his means of survival. As an observer, Krishen Khanna cleverly and beautifully highlights the juxtaposition between celebration and survival, drawing attention to those who are marginalised by society,” says Nagpal.

Khanna, the only surviving member of the Progressive Artists’ Group today, made Delhi his home after he became a full-time artist, creating many of his works in his studio at the Garhi Arts Village in East of Kailash and later in his studio in East Nizamuddin. His campus days as a school boy in the affluent settings of the Imperial Service College in London and a plush job at the National Grindlays Bank back in India gave Khanna an understanding of the trappings of privilege, something he would translate into a deeper perception of social structure in a poor, developing country in which the lower stratum of workers made a higher contribution to nation-building.

Traversing multiple stages in his long career, from an artist rooted to naturalism to abstraction to figurative artist, Khanna steadily rose to becoming one of the most important modernist painters of the country. His series of paintings on the bandwallas have been as much talked about for their style, aesthetics and language as his other famous works like Pieta (1988) about the crucifixion of Christ, Last Supper (1979), showing Christ and his 12 disciples, and Che Dead—The Photograph (1970) on the South American revolutionary Che Guevara.

Faizal Khan is a freelancer