By Faizal Khan

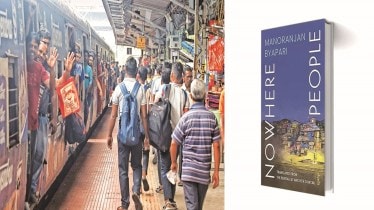

In the first pages of his 2018 Bengali novel, now available in English, Manoranjan Byapari puts a finger on the scale of its literary ambitions. He writes: “This story is about the people who live on the platforms.” Nowhere People, the translation from the original Bengali novel, Chhonochhaara, is about the invisible people who live on a platform at a railway station. Set in Jadavpur, West Bengal, the book follows the faceless rickshaw drivers who dwell on a platform, having no means to even rent a house, let alone own one. Their ownership of their rickshaws almost always rests with the rich and powerful, who control their lives at will.

Life on Platform Number Two

In Nowhere People, the home of the rickshaw drivers is platform number two because the ‘cleaner and tidier’ platform number one does not accept them. The lack of a home doesn’t stop the clockwork-like precision required to live in a railway station. “They went to bed after the last train left the station and they got out of bed as soon as they heard the whistle of the first train of the day.” It is into such a setting that a young man, the central character of the novel, arrives late one night. It doesn’t take long for the young man to become yet another member of the faceless. The community of rickshaw drivers, composed of “men from different religious groups”, even gives him a name, Nobo, because he hasn’t got one. They also teach him how to drive a rickshaw so that his social integration is complete.

Voices of the Invisible and Social Commentary

Byapari, who arrived in a refugee camp in West Bengal in 1953 with his parents from Barisal district of Bangladesh (then East Pakistan) as a three-year-old, weaves together a tale of a people who don’t fit into the familiar pattern of a society. At the platform number two of Jadavpur railway station there are rickshaw drivers from “West Bengal and East Bengal”, he explains, taking aim at modern society’s indifference to refugees. Thrown into a world of workers early in his childhood, which made him work in dhabas, wash plates and become a revolutionary, Byapari, who was once a rickshaw driver in Kolkata, gives voice to a community of workers whose everyday labour is of precious value to maintain the cycle of life for the rest of society.

Nowhere People’s Nobo and his fellow rickshaw drivers teach the other members of society a lesson or two about compassion and humanity. When he discovers a newborn baby abandoned on the platform, Nobo wastes no time in saving the child. Byapari gathers a galaxy of voiceless characters, whose world is by the railway track and whose slum dwellings change material and appearance as per the day’s and season’s demands. He tells us how hooch wars happen and headless bodies materialise on the railway. “Well, I had to go to prison for a few days,” deadpans Joga, one of the rickshaw drivers in Nowhere People, as he walks with Kajol, a domestic help. “They have to send someone to prison every month,” he adds, explaining the politics of raids by the revenue department on a hooch den run by Onjoli, another of the novel’s powerful characters. It emerges that Onjoli turned to the making of illicit liquor after her husband, a porter at the railway station, dies from a fall while carrying a heavy load on his back.

In Nowhere People, the author, a former chairperson of the West Bengal Dalit Sahitya Academy, and currently a member of the West Bengal Legislative Assembly, continues his criticism of inequalities and injustice. Though his canvas is limited to fringe dwellers, their portrait extends beyond boundaries to question the status quo of economic and social progress that keeps the inhabitants of Jadavpur’s platform number two and many others poor. Byapari, who was inspired to become a writer by Bengali writer Mahasweta Devi—a passenger on his rickshaw one day in Kolkata—presents a visceral description of the struggles of the poor, whose daily labour doesn’t figure on the nation’s economic indices. The lives of the novel’s characters like Nobo and Joga echo those in his previous works such as his Chandal Jibon trilogy. Seven years after he wrote Chhonochhaara, Byapari’s words about the world of the migrant workers have become prophetic as images of Bengali-speaking workers hounded in their homes shake the fragile foundations of an unequal society.

Faizal Khan is a freelancer.

Nowhere People

Manoranjan Byapari

Translated from the Bengali by Anchita Ghatak

Westland Books

Pp 356, Rs 599