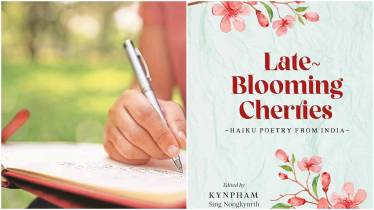

Haiku, a Japanese form of poetry, is now finding its way in India too, with poets across the country exploring this poetic form characterised by three lines and a 5-7-5 syllable pattern. While “historically, the haiku was born of nature and revealed the world of nature as it was before the mechanised age”, as Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih, editor of Late Blooming Cherries: Haiku Poetry from India (published by HarperCollins India) puts it, the Indian haikuists aren’t stopping here just yet. They are exploring contemporary themes of wars, refugee crisis, human suffering and even a humourous take on the administration.

“region’s backwardness

Explained by a road sign:

‘slow men at work’,” writes Nongkynrih in the Indian haiku anthology that he has co-edited with Rimi Nath.

“Stupas of Sanchi –

a monk under a tree, lost

in a mobile phone,” reads another haiku, where Nongkynrih has a humorous take on modern life.

However, he takes a dark turn to another one, where he writes:

“city’s cluttered drains

even unwanted infants

are thrown in”

“Yes traditionally, the Japanese have enjoyed and maintained a deep connection with nature, which is also reflected in their haiku. However, over the centuries, development has drawn man away from his natural roots. And urbanisation has brought with it competition, discrimination, intolerance, poverty, degradation of the environment, and a struggle for survival. Literature being a mirror of society, it is not a surprise that poetry, too, has adapted and is also inspired by this change in the human experience,” says Anju Kishore, whose startling haiku in the anthology reads:

“Bombed homes –

talks go round and round

the table”

Hard-hitting and universal, this could easily describe the war in Gaza or any other wars the world has witnessed in contemporary times.

“Although haiku are generally aimed at nature themes, a haiku’s power of brevity, vividness, and surprise element can be used as an effective tool for portraying and conveying human suffering and calamities. I have personally experienced the impact of such haiku, and also most of my award-winning haiku are about war and refugee crisis, says Indra Neil. A radiologist, his haiku has been featured in several journals.

“hopscotch

square to square

the refugee girl,” writes freelance editor Aparna Pathak.

One of the most startling haiku, a piercing reflection on contemporary Indian politics, is by A Thiagarajan, who retired as a deputy chief operating officer of a multinational bank.

“new actors –

Gandhi is shot

again,” he writes.

More can be written in longer poetry, and much more can be explained in prose; however, it’s the simplicity, the notion of ‘less is more’, where much is left unsaid and is left for the reader to decipher that does the trick, casting a deep impact making one think and reflect.

“Haiku might be brief and pithy, but they can convey a lot. It is like encapsulating an ocean in a grain of sand,” says Arvinder Kaur, who writes:

“Courtroom

How white the shirt

of the rapist”

Weaving much in less

While the poetry reads effortless, it’s no less effort to say more, explore universal themes, and bring out nuances of modern lives and human sufferings, in very few words.

In mere five words, Kaur writes:

“success –

a lone tree

standing”

Here, Nongkynrih points out that “haiku cannot even use many of the traditional devices of poetry, such as personification, anthropopathism, anthropomorphism, simile, and apostrophe. In this sense, it is challenging to grapple with complicated themes in a haiku.”

Neil, too, agrees that “it is definitely tough, to sum up the emotions and ideas in just three lines and compose it in such a way that the reader can appreciate not only the obvious imagery but also the underlying inference and intention of the poet.”

He adds: “It is the unspoken message left to the reader’s imagination that creates a lasting impression.”

However, “haiku are dealing with contemporary themes in a very effective way,” mentions Kaur. “The genre offers plenty of poetic licence,” she elucidates.

Nongkynrih, too, highlights haiku’s “unique quality of high suggestiveness deriving from its images, and the principle of ‘show, don’t tell’, which leaves it to the readers to discover the symbolic and evocative significance of the haiku image,” which makes this poetic form impactful.

“city’s cluttered drains

even unwanted infants

are thrown in,” reads a haiku by Nongkynrih, evoking grim imagery.

Haikufication of India

While haikus are generally summed up in three lines, Kala Ramesh takes it a step ahead by writing a one-liner:

“did Ganga dream of being the city’s sewage?”

India’s haiku scene is incomplete without Ramesh, the founder and director of TRIVENI Haikai India and external faculty member of Symbiosis International Universality, Pune, where she has been teaching a haikai course since 2012.

Haikai is the umbrella term for the many Japanese short verse forms, which include haiku, senryu, tanka, renku, and haibun. “Haiku culture in India is fast growing thanks to the untiring efforts of many haiku poets, especially Kala Ramesh, a senior distinguished poet and stalwart of haiku,” says Neil.

India’s haiku culture is surely growing, with more people taking up the craft and exploring wide-ranging themes.

“Over the last decade or so, there seems to have been a rising interest in India in haiku. Due to its contemplative technique and almost spiritual appeal, more and more people are turning to practising the form and its variants,” says Kishore. “Again, urbanisation is playing a part in this haikufication of the English poetry scene in India. The more mundane life gets, and the more commercial the living, what better than meditative poetry to keep one connected to oneself,” she adds.

Despite not being a mainstream literary genre in India, it’s interesting to see that the country has a dedicated haiku community. However, in the end, it all makes sense as this is also the land of shers and dohas.