A decade ago, India’s experience of Asian cuisine largely revolved around a narrow Indo-Chinese vocabulary. Today, Japanese katsu sandos sit beside Korean bibimbap bowls, Xi’an-style noodles and Thai salads in neighbourhood restaurants, malls and hotel rooftops.

New Silk Route

The rapid expansion of pan-Asian formats, from immersive cafes and casual dining to luxe reinterpretations, signals a fundamental shift in India’s palate, shaped by global exposure, social media and a widening supply chain that has made previously elusive ingredients commonplace.

In Delhi-NCR, this transformation is most visible in three distinct formats that have gained momentum—neighbourhood ambition, lifestyle-driven spectacle, and youth-oriented cultural translation. Together, Zuki, The Flying Trunk and Harajuku illustrate how the centre of gravity in Asian dining has moved away from traditional hotel dining rooms toward younger, more elastic consumer markets.

For years, the city’s Asian offerings were dominated by heavily localised Chinese dishes, but Zuki’s arrival in Noida in October marks a shift toward a more regionally faithful approach. “Noida had plenty of desi Chinese but very few places serving genuine pan-Asian flavours,” says owner Deepak Gupta. Led by chefs Veena and Vaibhav, Zuki treats Japanese, Thai and Korean cuisines as distinct micro-restaurants, each with its own mise en place.

The model depends on supply-chain improvements. “Fresh seaweed, good sushi rice, proper Korean pastes, these were difficult to obtain earlier,” notes Chef Vaibhav. Today, better imports allow Zuki to move diners from familiar tempuras and basil stir-fries to sashimi platters and hand-pounded Thai curries, bridging comfort and nuance for a fast-expanding suburban audience.

If Zuki reflects an appetite for precision, The Flying Trunk channels Asia through atmosphere and narrative. Positioned atop Novotel New Delhi City Centre, with Old Delhi’s minarets on one side and the city’s glass towers on the other, the rooftop bar-restaurant blends 360-degree views with an infinity pool and a menu inspired by Asian street markets from Kabul to Kyoto.

“Indian diners today are far more experimental and informed,” says Saumitra Chaturvedi, general manager, Novotel. “Earlier, Chinese or Thai staples dominated. Now people recognise ramen, bibimbap, robatayaki, katsu sandos , even the nuances of miso or gochujang.”

The demographic shift is broad. “While Gen Z is driving curiosity, families, business travellers, expats and older diners are also embracing lighter, ingredient-forward dishes,” Chaturvedi notes. The change is enabled by vastly improved sourcing: miso, kombu, Thai basil and Korean pastes, once difficult to find, are now available through specialised importers and better cold-chain logistics. Data confirms the choice of concept. “We recorded consistent double-digit growth in search interest for

Japanese and Korean food, and a rise in new restaurant openings,” he says.

If Flying Trunk turns Asia into sensory theatre, Harajuku brings Tokyo’s exuberance to India. Founded in 2021 by Gaurav Kanwar, the brand has quickly become a fast-growing Japanese dining concept, its footprint spanning cafes, bakehouses and experiential restaurants.

Kanwar traces the idea back to his time at Warwick, UK. “That’s where I first experienced Japan’s vibrant street food, playful cafes and dessert culture,” he says.

“Japanese cuisine in India was still mostly fine-dining. I believed it could be fun, approachable, part of everyday dining, not intimidating.”

Gen Z in particular has embraced the cuisine not as novelty, but as lifestyle. “For them, Japanese flavours aren’t intimidating but exciting,” Kanwar says. A decade ago, most diners began with sushi rolls. Today, the most requested items are jiggly pancakes, karaage, matcha lattes, mochi desserts and Japanese cheesecakes.

Authenticity remains the brand’s anchor. “We keep core flavours and techniques exactly as they are in Japan,” Kanwar says, referencing souffle-style pancakes, Hokkaido-inspired cheesecakes, kaiten sushi, karaage and ramen bowls. Harajuku does offer subtle “bridges”, a spicy mayo drizzle on certain rolls, and a mild heat adjustment in ramen, but these do not dilute the cuisine. “What we’ve seen is that customers quickly graduate from the bridge items to traditional dishes,” he explains. “Indian diners today are far more open to original Japanese flavours.”

Improved sourcing has been crucial. “Ceremonial-grade matcha, Japanese sauces, mochi flour, Kewpie mayo, sushi-grade seafood, these were inconsistent earlier,” Kanwar says. Better cold-chain networks now allow Harajuku to maintain Tokyo-level consistency across multiple outlets.

While Harajuku captures Japan’s playful, youth-driven energy, Burma Burma represents another dimension of India’s widening Asian appetite, a turn toward regional cuisines that were once entirely absent from the country’s dining vocabulary. Founded in 2014 by Chirag Chhajer and Ankit Gupta, the brand has grown to 20 restaurants and a delivery kitchen across major metros. The restaurant offers what co-founder Gupta calls “a holistic introduction to Burmese food, culture and happiness,” blending traditional flavours with contemporary presentation under the guidance of head Chef Ansab Khan.

Burma Burma’s ascent reflects a more introspective curiosity, a willingness among Indian diners to explore bold, sour, spicy profiles built on kaffir lime, balachaung peppers, fermented tea leaves and sunflower seeds. Its menu of small plates, hearty mains and inventive zero-proof beverages has helped familiarise a new audience with Myanmar’s layered culinary traditions.

This winter, the brand has gone deeper into its roots with ‘Comfort is Khowsuey’, a limited-edition menu that revisits the country’s most iconic noodle bowl through six regional interpretations. Each version draws on 12 years of culinary travel through Burma, guided by local cooks and custodians of heritage. The result is a reflection not just of technique, but of memory. Coupled with new zero-proof cocktails such as the Pandan Royale and Yangon Sunset, Burma Burma’s winter offering demonstrates how regional Asian cuisines now command the same emotional and commercial space that Japanese, Korean and Thai dishes have steadily occupied in the past decade.

Reassertion of technique

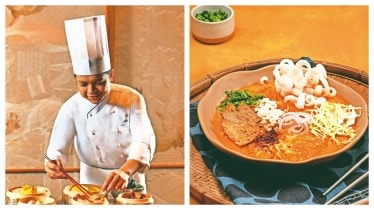

As the new guard reshapes consumption patterns, Delhi’s longstanding institutions have responded with reinvention and renewed culinary precision. Among them, House of Ming at the Taj Mahal, New Delhi, remains the capital’s most durable symbol of Chinese dining. Established in 1978 and re-imagined in 2022, the restaurant has retained its position by deepening its regional framework rather than diluting it. The focus on Sichuan, Cantonese and Hunan cuisines provides a degree of articulation now expected by a more informed diner.

“Each region offers a distinct culinary language,” says Anmol Ahluwalia, area director—operations and general manager. Executive Chef Kaushik Misra translates this philosophy into an expanded dim sum repertoire with imperial preparations, lotus-wrapped delicacies, baked and poached textures, and menus featuring techniques such as oil-braising, subtle chilli fermentation and refined wok work. The promotional Sichuan menu, with water-boiled chicken dim sums, steamed red snapper with pickled Chongqing chillies and oil-braised duck, illustrates a kitchen confident in its roots and responsive to contemporary demand.

A similar confidence animates Madam Chow, the new Chinese restaurant at The Oberoi, Gurugram. Housed in a glass pavilion overlooking the hotel’s reflective pool, the restaurant merges theatrical design with the culinary authority of Chef Wong Kwai Wah and Chef Mark Lin, whose repertoire spans Guangdong and Sichuan. Dim sums such as Lychee Bonsai Bao and Harmony Siu Mai sit alongside imperial roasted chicken and modern finales like Sichuan peppercorn ice cream. Its arrival reaffirms the hotel sector’s growing investment in Asian cuisine as a site of innovation rather than predictability.

Yet the region’s most culturally resonant newcomer looks inward rather than outward. Tangra—Tales of Chinatown, newly launched at The Westin Sohna Resort & Spa, draws from the storied Hakka cuisine of Kolkata’s historic Chinatown. In contrast to the forward-leaning theatricality of other new entrants, Tangra is steeped in memory and community. Signature dishes such as Chimney Soup, Shao Mai, Tai Po, Yam Mein noodles, Tangra-style chilli chicken and paneer, appear alongside seafood such as Golden Garlic Lobster and Mandarin Chilean Sea Bass.

Authenticity is reinforced through sourcing. Select ingredients come from traditional family-run makers in Kolkata’s Chinatown, the custodians of recipes dating to the 1950s. “Tangra is a story brought to life,” says Rahul Puri, multi-property general manager. “We wanted guests to remember its warmth and character.” For Chef Amit Dash, who grew up near Kolkata’s Chinatown, the restaurant is a personal homage: “Great cuisines are born at the crossroads of culture. Tangra preserves centuries of heritage in every bite.”

If the older establishments assert historical depth and technical continuity, and the new entrants respond to youth culture and lifestyle shifts, the middle ground where India’s mass-premium diner now resides is increasingly defined by regional curiosity, improved sourcing and a willingness to experiment.

Across metros, this new Silk Route runs through malls, rooftops, and suburban lanes. It is a landscape where sashimi platters sit comfortably alongside Hakka chilli chicken, where Japanese cotton cheesecakes are as familiar to Gen Z as dim sum trolleys once were to their parents, and where diners no longer “try” Asian food, but inhabit it as routine and as comfort. What lies ahead is likely a deepening regional specificity, more immersive formats, and a continued interplay between nostalgia and novelty.