Reading for pleasure—fun-filled adventures, the thrill of a mystery, stories of friendship, folk tales—seems to be out of vogue in children’s literature, giving way to complicated concepts like inclusivity, equality, diversity which children are exposed to at ages as early as 2-3 years.

Back in the day, a Looney Tunes episode meant the younger versions of Disney characters having a fun day in diapers. Tom & Jerry proved to be an interesting chase game of friendship and hate between its characters. The feel-good and ordinary portrayal of cartoons like Oswald, Pingu and Noddy were a treat for the young.

However, children’s taste is no longer the same in the content they want to consume and the resultant shift is visible in the way cartoons, comics and story books are shaping up today.

A ten-year-old tech-savvy Ryder captains six brave puppies, who work together on important rescue missions to save the residents of the Adventure Bay community. This is the crux of the animated children’s cartoon series Paw Patrol which is popular among children today.

The series that first released in 2013 is in stark contrast to the sensibilities and likings of the children who grew up till the 90s. Cartoon series or storybooks today are on an important mission—to make the future generation aware of concepts like inclusivity, equal rights, diversity, gender, racism, and more.

Also Read: Under 50 politicians around the world

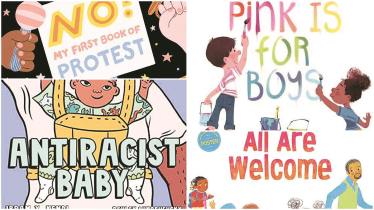

Take for instance, the 2020 published book No!: My First Book of Protest by Julie Merberg that has been written for children of age 0-3 years. The book talks about important protest movements by popular figures like Malala Yousafzai. Antiracist Baby by Ibram X Kendi, published in 2020 has also been written for the same age group. Back in the day, racism and protests were topics that were introduced only in school textbooks. However, as the world steers towards an inclusive and diverse future, these subjects become the necessity of the day, but to impart them at beginners’ level, starting right from 0-3 years of age is another matter of discussion.

With maturing sensibilities in children born in technology-driven times, one also observes an inclination toward technology early on. It is not uncommon to see a 2-4-year-old operating a phone all by themselves and putting on their favourite nursery rhyme or cartoon series. In fact, many times, experts have feared that the inclination toward using phones and technology may lead to decline in reading habits among the young.

Nalini Ramachandran, children’s book author and editor, agrees that the present generation has several other interests or distractions, as compared to reading. “But children mostly cultivate their reading habit from people they see around them—parents, teachers, friends. Indian children’s literature, which is continuously evolving, has enough on offer for them to choose from. A lot of experimentation is happening, in terms of the themes, character diversity, the telling and the formats. Books in Hindi and other regional languages, graphic novels, audiobooks and e-book platforms have made their presence felt as well. And then, there are litfests for children, which introduce them (and grown-ups) to whole new worlds through workshops and author sessions. So, the children’s literature sector in India has much scope for growth, and it is moving in a good direction,” says Ramachandran.

Jataka or Panchtantra, Tinkle, Archie and other popular children’s comics and storybooks that were once constant companions are now either being consumed through audiobooks or videos. This does not mean that they go out of circulation but they have innovated with time to stay relevant. Archie, which first appeared in 1941, for instance, gave their characters a modern retouch.

Amar Chitra Katha, publisher of children’s books too has adapted to audio books. But does that entail that reading habits are declining in children?

Preeti Vyas, president & CEO, Amar Chitra Katha, calls it an ‘urban myth’. “There are many more stimuli and entertainment options than a decade ago, but today’s parents and teachers have an increased understanding of the importance of the reading habit for a child’s overall holistic development. There are more children’s books from Indian and global publishers available now than ever before. Schools all over the country, even in small towns, are organising their own literature fests and book weeks,” says Vyas.

Vyas underlines the constant evolution they have gone through in order to sustain themselves with the changing times. “In addition to continuously evolving our writing and art style to suit today’s generation of readers, we are present on all possible content platforms. We believe that as publishers, we are storytellers first and foremost, and should remain platform-agnostic,” she says.

Pay parity

When it comes to pay parity in the publishing industry, several authors share that children’s writing fetches lesser income as compared to writing non-fiction or fiction. In fact, there’s a wide gap in children’s literature in India, according to experts. Academic books dominate the children and young adult literature market while non-academic books find few takers. The low wages paid to authors of children’s literature driven by low readership further adds to the pressure.

Nalini Ramachandran explains the workings of the payment system in the industry. “ In the commercial picture books market (picture books form a large part of children’s literature), the author is usually paid a lump sum, and the rights to the work are transferred to the publisher. So, that is the only payment the author receives, irrespective of the number of copies sold by the publisher over time. Within the picture book market, some organisations work under the creative commons licence. Here, too, the author is paid a lump sum. The licence allows anyone to use this open-source material (even modify and reuse it, with appropriate credits). Some organisations sell some titles created under this licence, but the work is primarily created so that it can be freely accessed on a public platform,” she says. Storyweaver by Pratham Books works on the same model. Depending on their future plans and other factors, sometimes, some picture book publishers may agree to make room for royalties. Long-form books, which include novels, novellas, and chapter books (both fiction and non-fiction), mostly follow the advance against royalty arrangement. So, depending on the contract and the number of books sold, the author may receive royalties. The lump sum paid to picture book authors is often lesser compared to the advance paid to long-form book authors. This, again, is based on several different factors.

Hence, being a children’s writer in India may often not provide an income enough to sustain oneself. “A children’s author I spoke with recalled how writing children’s books could not be her main job because it hardly paid. She instead had to treat it as her hobby and take on other jobs as well to make a decent living,” shares Kavita Gupta Sabharwal, co-founder and curator of Neev Literature Festival.

Ramachandran, who says she always wanted to write children’s literature, too, agrees taking up editing assignments of coffee table books, magazine issues and editing for academic papers to sustain herself. “People also think they can make money from workshops but not everybody has the reach or connections to conduct workshops,” she adds. Sabharwal says the unsustainability and non-existence of children’s literature market makes authors reluctant to choose children’s writings as a career path. “Careers for children’s writing is dwindling. What they get paid is very less and rarely exceeds Rs 50,000 for a book. There are several children’s writers in India. But the challenge is that they are doing it as a side thing,” shares Sabharwal.

Preeti Vyas of ACK accepts that children’s book authors and illustrators are not as well paid, but that’s largely due to the price ceiling of children’s books in India. “A full colour picture book in the US would be sold at retail for a minimum of $10-15. Here in India, we are unable to charge more than `250. This price ceiling puts tremendous pressure on the entire chain from author to publisher to distributor to retailer. But with growing awareness, literature will only grow. I do not predict a decline,” she explains.

As for Ramachandran, she believes that the budget allocations aren’t equal between children’s genres and other genres in publishing, which, in turn, leads to disparity. “Some amount of parity can be achieved only when the literature genre itself is treated with importance. It’s also possible that the differences occur because there is this misconception that children’s books are easy to work on. Only those who work on them, day in and day out, can tell you that it is a lot of hard work,” she adds.