Before the “plum-pudding jollity” of the British Raj was adopted by Delhi’s elite in the decades following the fateful year of 1857, the Mughal capital had a distinct culture nurtured by the Red Fort (then in disorder, and surviving on empty coffers). Few traditions from the gone by era have survived the test of time. Ceremonies were regularly conducted in the celebration of different Indian festivals at the royal court as several Mughal Emperors had Hindu wives and Hindu mothers and they embraced the composite culture mores. Indian culture is unique in more than one sense because it has been shaped by etiquettes, customs and influences of different religions of the land. The borrowing of traditions remained consistent for centuries. Today, fireworks have become an essential part of Indian festivities — whether the occasion is Diwali, Guru Nanak’s birthday, wedding ceremonies or independence day. But who really started lighting up the sky to celebrate?

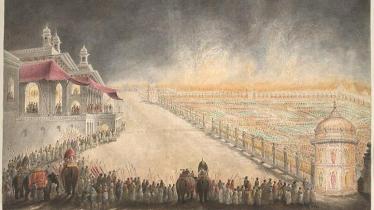

Interestingly, gunpowder was invented in China in the 9th century and the Tartars had conquered the Chinese mainland in the 13th century by employing explosives. The British had used gunpowder extensively to annex large swathes of Indian territories. Because gunpowder was not easily available outside atish khanas of the Indian rulers, fireworks were accessible to royalties alone. The celebrations at Red Fort were emulated in the city and fireworks were their main attraction, which drew crowds to the ramparts of the fort.

Francois Bernier in Travels in the Mughal Empire (1659-67) writes, “The festivals (in the Red Fort) generally conclude with an amusement unknown in Europe — a combat between two elephants; which takes place in the presence of all the people on the sandy space near the river: the King, the principal ladies of the court, and the Omrahs viewing the spectacle from different apartments in the fortress.” The animals during these fights were separated only when fireworks were exploded between them. Being “naturally timid” and fearful of fire, Bernier points out, “is the reason why elephants have been used with so very little advantage in armies since the use of fire-arms”.

The fireworks in Delhi on the Muslim festival of Shab-e-Baraat, which falls before the holy month of Ramzan, began much before the Mughals moved their capital from Agra to the city. In 1258, the first celebratory fireworks were recorded when Mumluk Sultan Nasiruddin Mahmud Shah welcomed envoys of Mongol ruler Hulagu Khan to his capital.

According to medieval historian Firishta’s Tarikh-i-Firishta, 300 cartloads of fireworks were put to use on the occasion. The evidence of display of fireworks on Shab-e-Baraat was also recorded during the reign of Tughlaq dynasty’s Sultan Feroz Shah who had established his capital near the present day old city of Delhi, where his dilapidated fort still stands.

Fireworks on Shab-e-Baraat remained constant during the Mughal days and they became an essential part of elaborate Diwali celebrations at the Red Fort. On Diwali nights, Red Fort’s burjs were all decorated with oil lamps and the emperor watched the night’s festivities from his burj. During the day, as was an old Mughal tradition for birthday celebrations, emperors were weighed against gold and silver, for distribution among the poor. Fireworks were a great source of Mughal amusement back in the day and an essential part of celebratory occasions. Celebratory cannons were also fired on different occasions. The Ram Leela processions that still hold charm in Old Delhi, were started in the city by the Mughals.

The festival of light and fireworks have no linkage if one goes by how the festival was celebrated centuries ago. The tradition of celebratory fireworks on Diwali, according to historians, began only in post-colonial India. A display of celebratory fireworks has become a part of composite culture of India, which has gotten in its present shape due to a fine mingling of different cultures and religions. With the thick cover of dangerous smog enveloping different India cities in its choking haze every year at the onset of winter, it is quite appropriate to weigh the question whether the tradition of celebratory fireworks on Diwali should be abandoned for good in the best interest of everyone.