By Shubhangi Shah

Indian textiles are famed worldwide. Not just that, people’s attire, textiles, and craft differ from region to region, adding to the cultural richness. Whether it is Gotta Patti of Rajasthan or Kantha of West Bengal, Kanchipuram silk of Tamil Nadu or Khneng of Meghalaya, or the famed Zardozi, or Zari work, which came from Persia (Iran), each of these possess their distinct qualities, collectively enhancing India’s textile richness. The travesty, however, is that while we continue to take pride in the crafts, the countless men and women behind them are largely hidden and often forgotten.

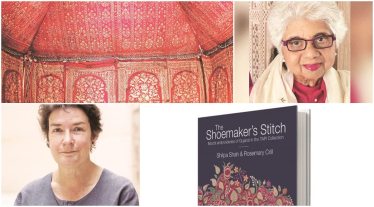

The Shoemaker’s Stitch: Mochi Embroideries of Gujarat in the TAPI Collection by Shilpa Shah and Rosemary Crill can be called an attempt to undo that. Shah is the co-founder of the Textiles & Arts of the People of India (TAPI) collection, while Crill was a senior curator of South Asia at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, for over three decades until her retirement in 2016. And together, they have created this collection, which puts focus on the Mochis, a community of cobblers, saddlers, and shoemakers, from Gujarat’s Kutch and their craft—the chain-stitch embroidery, locally known as Aari, after the shoemakers’ tool.

The collection, which spans from the 18th-20th century, takes the reader on a visual journey through the streets of the Mochis, and the fine Aari work by them created for the local rulers and patrons, the Mughal court, and for exporting to Europe.

And what rich work they created for purposes as diverse as you can imagine. “It has lent itself to all types of design from the floral arabesques of the Mughal period and the hybrid chinoiserie of the western export market to the stylised flowers, parrots and female figures found in colourful garments and hangings made for local patrons in the 19th century,” the book reads.

Crill and Shah have known each other for 20 years. She (Crill) “has known the range and depth of the TAPI collection,” says Shah, adding, “ The pandemic provided a window for the collaboration (for The Shoemaker’s Stitch) to happen.”

The senior curator, who had earlier collaborated with Shah and her husband Praful on two other books, says she has “watched them create one of the world’s most superb collections of Indian textiles”. “So this was a great opportunity to focus on another specific aspect of their collection,” she adds.

“Mochi embroidery has been recognised as one of India’s finest textile crafts for centuries, and yet this is the first book (as far as we are aware) to concentrate on this art form,” says Crill.

Speaking on the intent behind creating this collection by putting attention on the artisans and not the patrons, Shah says it is because they (the artisans) are the “starting and the end point of any craft”. Similarly, “the majority of artisans in India (and elsewhere) remain anonymous, so it is important to record the unusual amount of family history that has been gathered by the Mochi community itself,” says Crill.

The collection also debunks the myth that all the Mochi embroiderers were men and gives names, photographs, and family connections of several noted female embroiderers.

Far from the general academic way of documenting history, art, and culture, The Shoemaker’s Stitch takes the readers on a visual journey, a journey covered by the Mochi’s stitch, spanning from Bhuj in Gujarat and Jaipur in Rajasthan to Sindh in Pakistan to as far as Europe and Zanzibar. It follows a traditional catalogue format, starting with three brief essays followed by a catalogue illustrating the Aari work spanning almost three centuries. Speaking on the style adopted, Crill says, “We hope it is readable as well as being both informative and attractive, and, of course, the beauty of the pieces makes the whole book visually appealing.”

“Whereas prior to the 2001 earthquake, Mochi Street had 30-40 Mochi families residing there, it now has just four, and sadly, for the past 70 years, has been bereft of a single practitioner of the stitch-craft associated with their name,” the writers observe about the dwindling practice of the textile craft within the community. There can be multiple reasons behind it, such as a lack of patronage, popularity of modern and machine-made clothes, etc. While many from the Mochi community have given up the practice, many, breaking the caste, religious and gender boundaries, have taken it up, continuing the craft in their capacities, the collection’s creators have noted and documented.

A lot has changed since the time the Aari work developed and won global repute. The world underwent industrialisation, India became independent, and the local rulers lost their authority. In the 1990s, as India’s economy opened, globalisation paved the way for western fashion and clothing in Indian markets. Understandably, it has had a considerable impact on this traditional craft.

“Fashion has not stood still,” comments Shah. The same applies to our traditional attire and social customs, she says, adding that “over the last century, consumer taste has radically been transformed with western influence”. For example, a century ago, ghagra-cholis were the everyday wear of Gujarati women. This has changed considerably. As a result, chain-stitch embroidery, too, has had to find new, contemporary consumers with changing aesthetics and a new group of artisans capable of responding to these changes. “That it has, indeed, done so, brings cheer,” says Shah.

Similarly, Crill observes that it is never in the interest of an art form to stagnate and repeat the same patterns over centuries. “The adaptation of fine chain-stitch embroideries to modern designs and uses, whether done by artisans of Mochi heritage or others, can only enrich the craft and keep it alive,” she says.

On the careful balance between adapting to today’s times while preserving the heritage, they say that Indian embroidery has what it takes to adapt to the modern world. “However, it is important to preserve and publicise historic examples as an archive to inspire future makers and scholars,” says Crill. At the same time, the TAPI collection’s creator believes that “while we aspire for a future unencumbered by the confines of the past, it is vital that our artistic heritage is not erased from memory”.

“The splendour of Mochi embroidery is a tale that needs retelling,” she adds.

The Shoemaker’s Stitch: Mochi Embroideries of Gujarat in the TAPI Collection

Shilpa Shah & Rosemary Crill

Niyogi Books

Pp 220, ₹4,500