The world’s largest democracy with a 90 crore electorate (more than the combined population of Europe) is set to elect its 543 members for the 17th Lok Sabha in 7 phases from April 11 to May 19. The Indian elections have always posed great challenges for anyone decoding the factors impacting voting patterns. Against such a background, it will be interesting to link India’s elections with social and economic aspects.

Firstly, how does India stack up in comparison to voting patterns around the world? Voter turnout data published by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA) indicates that, as per the most recent national parliamentary elections for major countries, France recorded the lowest turnout percentage (43%) while Germany has the highest (76%). On this parameter, India is also doing well as voter turnout rate has improved significantly to 66.4% in 2014, as compared to 58.2% in 2009. The 2014 voting percentage was the highest since 1984.

As per male and female voter turnout rates, the gap has declined significantly in 2014 and has been declining from 1991, when the gap was more than 10%. Extrapolating Asembly election voting patterns in states post 2014, we believe such high female turnout in elections might continue in 2019.

For example, one proxy for increasing women empowerment is the number of accounts that have been opened through the Jan Dhan and Mudra schemes. There is now increasing evidence that Jan Dhan accounts are acting as a vehicle for remittances, resulting in more and more women taking independent decisions. We estimated the state-wise women PMJDY & Mudra accounts by taking the national percentage share, which is 73.6% for MUDRA and 53% for PMJDY. The results show that in all the ten states, the turnout rate for women in the subsequent Assembly elections post 2014 has improved significantly (by an average of 10%) as compared to the 2014 Lok Sabha general elections. States like Madhya Pradesh, where both Mudra & Jan Dhan accounts have been opened in very large numbers, have seen an increase in the women turnout rate by 18%.

However, there is a point of concern. Comparing Census and Election Commission data, we estimated that there might have been 1.24 crore missing women at the time of 2014 elections in 10 states only. We define missing women as the ones who are eligible to vote but have not yet registered themselves as voters. This is alarming since it means that approximately 1.24 crore women may not have exercised their constitutional right to vote in their state of domicile. So, to improve the women turnout rate in India, all stakeholders, starting from the Central government to the media as well as the civic society, should encourage, facilitate and promote women to get themselves registered as voters.

Of equal importance and hitherto unexplored in Indian elections are the socio-political factors like population size, age, educational attainment, political interest and economic backwardness. We believe that these factors play a major role and, over the years, have been the major driving factors behind voter turnout rates. The Multi-Dimensional Poverty Index (MPI) by Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative assigns values to Indian states based on the deprivations that each person faces with respect to education, health and living standards. The states were ranked based on MPI and were compared with the rank assigned to states based on voter turnout rates. Interesting patterns emerged. Certain northern states like Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Jharkhand, with higher MPI, have lower voter turnout. Interestingly, these states have low literacy (women) and per capita incomes. Further, most of the North-East and Eastern states have higher turnout rates and varied levels of poverty. However, states including Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Goa, Tamil Nadu, Haryana and Punjab have a high voter turnout rate and lower level of deprivation. These states have higher per capita incomes than the national average and a higher literacy (though Andhra Pradesh and Haryana have lower women literacy). Thus, voting patterns might be literacy agnostic.

In addition to this, another important aspect that leads to a low turnout is interstate and intra-state migration of both males and females. Over the years, mostly males have been migrating from one state to another due to various reasons. Estimates of net migration, once mapped with the percentage of voter turnout amongst major states, show states like UP, Bihar, Odisha, Rajasthan and J&K have net “out migration” and, consequently, low voter turnout rates. Steps might be initiated to bring this growing chunk of electorate back into the voting process by making suitable changes in the existing electoral regulations. We believe this can be made effective by rigorously linking the Aadhaar Card with the Voter Identity Card and introducing a system of absentee voting procedure, like in the US.

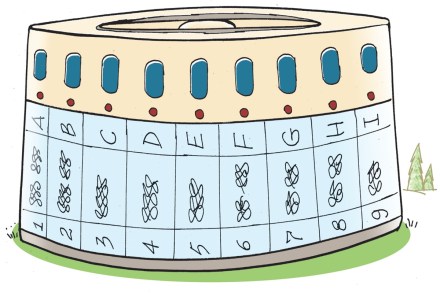

Finally, a food for thought. Since only 543 Lok Sabha constituencies represent 130 crore people in the country, is it worthwhile to look at the legal provisions on delimitation of parliamentary constituencies? This is crucial to rationalise population on a per-seat basis (to properly cater to the needs of people and constituency), which is currently at 15.6 lakh per Lok Sabha constituency. Even in the smaller countries like UK, Germany, Italy, France, etc, the number of elected representatives is higher than the strength of the Lok Sabha in India! But can India afford such in terms of fiscal implications in an era of cooperative federalism where states also have large elected representatives? Let this debate begin!

Group chief economic advisor, State Bank of India. Views are personal