By Kabir Deb

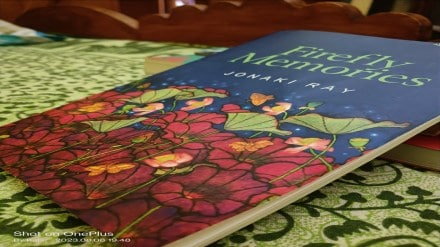

The sting of a memory is not an acidic reality. It has the chimera of luciferin and a certain kind of absence which maximises its visibility. Jonaki Ray’s debut book of poetry ‘Firefly Memories’ focuses on the existential idea of memories. It gives an individual identity to every piece of a memory that gets magnified during absurd moments and delicate situations. The quality of writing lies in how it handles its content, especially when it comes to a book that has the responsibility to show the footprints of a singularity – in this case the poet handles the odds and evens of memories.

Food is one of the many things that remind us of good and bad times – light and dark instances – tough and rough people. In Ray’s poem ‘The Secret to a Good Biryani’, the poet composes and compares some of the major issues with the ingredients involved in the process of making Biryani. When the saffron-flavoured rice of a partially cooked biryani, cold and tasted by time, blends with the aching of a diasporic domination, the poet exposes the memory of a touch. The acceptance of the rejected or ignored past, by living in a present that is always about remembering what it never lived. Jonaki says that even the best-tasting Biryani has blur gaps. The first bite itself gives the news.

The poet writes:

“You wait for the spices to mix and the chicken to infuse the rice.

You hope to mix with the people here.

You source friends amongst the locals unsuccessfully.

You integrate with the Desis instead.

Visit temples that you ignored back home.

start wearing saris,

cheer for the cricket teams

that you ignored earlier,

celebrate all festivals,

and pity the people back home.”

Misogyny and marriage go hand-in-hand whenever we start synthesizing trust over a dying relationship. The first step tells a lot about the many steps that follow it without knowing anything about the consequence. Jonaki’s poem, ‘Photosynthesis’, explores the communion through the lens of a woman in solitude. So, her perspective towards a community of bacteria is that of a learner. She learns that on the way to explore the universe outside our body, we left the one that exists inside our mind. The poet traces the physical reality of red flags in a relationship, and swirling through the thoughts of a lady in her mid-twenties weaves survival that is both – calm and chaotic.

Jonaki writes:

“As I watched the green tresses-like DNA fronds

and red-centred mitochondria helices

of the bacteria simulate on my computer, I fell:

For love, and hope, and the American Dream.

I ignored the warnings – his monitoring my calls, cutting me off

from friends and everything familiar, the sudden explosion of rages.”

‘Tomorrow is a Many-Eyed Goddess’ is a disturbing poem, and easily cuts like a knife. It holds the home of the world, and the world of a home. Time or Kaala establishes the ground of the poem and all the instances mentioned by the poet. The stereotypical perspective of people, how they act according to the thoughts or ideas they feed upon, and to surf against poverty, to find an original identity, one has to ponder upon stigmas. For that, the necessity is to growl through a pile of grief, guilt and galvanized rhetoric. The carelessness is not innate. It always comes out like a loud result.

“That one day we will have our own ghar –

home is not this broken shanty.

Home is not this cold, cold place that we have come to

for the few hazaar taka notes in our hands.”

To give a body to a being which is not breathing is the best thing an artist can ever do. In the poem, ‘Reverse Astrology’, Jona does the same with affection, sharpness, and by being a quiet biologist. The movement of a person living in a house always goes with the anatomy of the abode. Jotting down words based on a visual piece has been the work of poets of Medieval times. Jonaki draws the entirety of the painting and coalesces it with the contemporary idea of predictions and premonitions. ‘The house is a withered ginger’ – the line slows down life, cleans the words we must utter whenever we feel a jolt, and solidifies how alterations in life come with the being only.

Jona gives a reality by writing:

“The house has tom-cat windows

fat with fungus and mould

Inside, the sofas droop under covers

like Hindu widows mourning their own.”

Amidst the oppressive spread of industrialization, when Nabarun Bhattacahrya writes: ‘this land of death is not my country’, we get triggered. The trigger changed an entire generation, and still is found written over the damp walls of Kolkata. We notice the change. Ray’s poem, ‘The Man Who Predicted His Own Death’, works like an imprint of what the subcontinent is suffering from: a bad thrust of maligned capitalism. On the way, we lose the major bridges that connect the parts we live in, and those who never got to visit. The language of the trees is kept under the genre of romance because we do not let them slip into our daily lives. Now all we have is a sudden demise.

So, the poet writes:

“A tree is not a forest

But even trees know

that to survive

they have to be together,

and not cross into each other’s canopy

in the sky, and offer food to each other

through their roots in the ground.”

‘Firefly Memories’ is a book that has documented almost everything we try to write to say sometime, somewhere. Drenched with mindful development, Jonaki’s poetry offers a sense of relief to those who have a certain inclination towards preservation of memories irrespective of the state they hold. It cannot be said that the poet owns these memories exclusively, and she verifies the inclusiveness through various poems. It unabashedly accepts everyone with warmth and sincerity. With a collection of sensitive poems, Firefly Memories offers people a space to sit, talk and think about the various fragments of the one life we have for us, and others.

Book Reviewer is an author cum poet based in Karimganj, Assam. He works in Punjab National Bank and has completed his Masters in Life Sciences from Assam University and is presently pursuing his MCW from Oxford University, London. He is the recipient of Social Journalism Award, 2017; Reuel International Award for Best Upcoming poet, 2019; and Nissim

International Award, 2021 for Excellence in Literature for his book ‘Irrfan: His Life, Philosophy and Shades’. He runs a mental health library named ‘The Pandora’s box to a Society called Happiness’ in Barak Valley.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal and do not reflect the official position or policy of Financial Express Online. Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited.