By Atanu Biswas

The fundamental dilemma of political economy that “forces us to ask what form of political system is required so that a viable, private market economy is a stable policy choice of that political system” was postulated by Stanford professor Barry R Weingast in 1995. In response, in his 2010 book Coalition Politics and Economic Development: Credibility and the Strength of Weak Governments, economist Irfan Nooruddin contested the conventional wisdom that coalition governments obstruct necessary policy reform in developing nations. According to a novel argument put forth by Nooruddin, institutionalising deadlock actually promotes economic growth by stabilising investor expectations and lowering policy unpredictability. The claim was supported by company surveys, case studies, and national economic data.

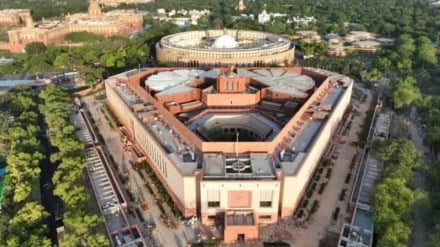

How about India? Following the Lok Sabha elections, which saw the return of a coalition government to power after a 10-year hiatus, the debate about potential economic advancement under coalition regimes gained relevance.

It’s interesting to note that there is no clear correlation between coalition governments and GDP growth. The Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government oversaw an average of 6.8% GDP growth in India during 2004-14. Interestingly, GDP increased at an average rate of 6.9% during the first five years of the UPA-I, when Congress held a meagre 145 seats in the Lok Sabha. The GDP, however, expanded at a slower rate of 6.7% during the UPA-II government of 2009-14, despite the Congress gaining 206 seats in the Lok Sabha.

The GDP increased at a pace of 6% during 2014-24 under the Modi regime. Excluding 2020-21, the pandemic’s initial year, in which a strict lockdown resulted in a 5.8% drop, GDP growth during the Modi administration was 7.3% over a nine-year span.

In the two years that Morarji Desai’s cabinet was in power, during 1977-79, GDP increased at a pace of 6.5%. During the precarious coalition politics of 1989-2004, the growth rate was 5.6%, although on average during Vajpayee’s six-year premiership, it was slightly higher at 5.8%. On the other hand, in the 15 years of Congress’s one-party rule preceding the Desai government, the GDP grew at a rate of only 3.8%. According to expert evaluations, coalition governments have generally been successful in promoting economic growth, but have had some difficulty reining in inflation. However, one must remember that a nation’s economy is influenced by a wide range of variables, including the state of the world economy and politics.

Importantly, the revolutionary and unquestionably daring policy decisions made by various coalition governments throughout the 25-year period from 1989 to 2014 significantly altered the nation’s social and economic landscape. The government of PV Narasimha Rao, which was not only a coalition but also a minority one, would invariably be the prime example. It brought a plethora of reforms, like doing away with centralised planning and abolishing the licence-permit raj to allow the Indian economy to compete globally. It brought about market-oriented economics and privatisation. Reforms were actually required in the wake of the significant spike in oil prices in August 1990, which left India facing an untenable balance of payments position, depleted foreign exchange reserves, and massive capital outflows, thus increasing the likelihood of default. During this administration, India also joined the World Trade Organization.

Then finance minister P Chidambaram introduced a “Dream Budget” in 1996-97 during the brief HD Deve Gowda regime, which proposed reducing income tax rates, corporate taxes, and customs charges as well as eliminating the corporation tax surcharge. Chidambaram’s Voluntary Disclosure of Income Scheme was intended to curb black money, but it also gradually widened the tax base and raised tax buoyancy.

To privatise failing public sector organisations, the government of Atal Bihari Vajpayee established the department of divestment. When Vajpayee’s government pushed to buy a 20% share of Sakhalin-I oil and gas reserves in far-east Russia in 2001, India made the single largest foreign investment. In order to maintain fiscal rectitude, the government also drafted the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management law. Additionally, it introduced the New Telecom Policy by switching from fixed licence payments to a revenue-sharing model for telecom companies. Through the PM Gramin Sadak Yojana, this administration concentrated on improving connections and infrastructure in rural areas. It also introduced the Information Technology Act of 2000, which laid the groundwork for India’s current status as a thriving e-commerce powerhouse.

The Right to Food initiative by Manmohan Singh’s UPA-I government was aimed at ensuring that no Indian would go hungry. The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, introduced by the UPA, gave the rural poor minimum employment. The Singh government began developing Aadhaar, goods and services tax (GST), and direct benefit transfers. In actuality, value added tax was a precursor to GST. The farmer loan of Rs 65,000 crore was waived by this government. Singh’s government also deregulated fuel prices.

Therefore, as argued in Nooruddin’s book, it’s not always the case that a single-party government is beneficial to the economy and that a coalition government will result in policy paralysis. In fact, the 1991 Indian economic crisis is frequently attributed to the Rajiv Gandhi government of 1984-89 as its primary cause. Thus, I don’t see reforms like Made in India or the explosive rate of infrastructural growth stalling under today’s compulsive coalition government. However, some politically sensitive measures may find it difficult to pass. Furthermore, as multiple stakeholders are engaged in a decision-making process, any reform like GST and demonetisation as well as their modus operandi may also require extensive negotiations. However, with a coalition government, it’s unavoidable.

Moreover, the huge consumer market in the world’s most populated country would invariably continue to draw big-name investors like Tim Cook, Bill Gates, and Elon Musk. The economy would continue to boom.

The author is a Professor of Statistics at Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal and do not reflect the official position or policy of FinancialExpress.com. Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited.