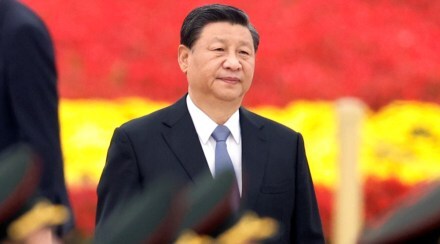

President Xi Jinping’s expected re-appointment for the third consecutive term, if not for life, as general secretary of the Communist Party of China is a momentous development in the country’s history. His ascendancy to a position of supreme power like Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping to preside over the destiny of a 1.4 billion-strong nation was perhaps foretold when he began his second term in 2017 without designating a party leader as successor and the Chinese Parliament in 2018 scrapped the two–term limit for the general secretary post. Very little is known about Xi’s personal life except that he was a “princeling”, whose father Xi Zhongxun was purged by Mao during the Cultural Revolution but later rehabilitated by Deng. An interesting factoid was that the reformist father oversaw the creation of China’s first special economic zone at Shenzhen. While his father and Deng believed that the CCP’s grip on power would perhaps be more secure if it relaxed control over certain aspects of the economy, Xi did the opposite. Motivated more by the fear of the party collapsing—as happened during the Gorbachev era in the erstwhile Soviet Union—Xi strengthened the CCP’s hold. “Government, military, society and schools—north, south, east, west and centre—the party is leader of all”, he said at the Congress five years ago.

Also Read: Xi’s third term promises more risks than rewards for India

Xi also overturned Deng’s key precept to keep your head down, hide your strengths and build-up capabilities to one of projecting China’s power internationally, although in his address to the 20th Congress he stated that the country does not seek hegemony. This is where he confronts the biggest challenges. China has a larger economy than the US in terms of purchasing power parity. It has built up a world-class, technologically advanced military. That it has emerged as the key strategic competitor to US’s global dominance has been acknowledged in the latter’s national security policy. But China cannot play a larger international role if its economy is faltering. Gone are the days when it grew at 10% per annum since 1978 that enabled 800 million people to rise from poverty. The dragon’s growth currently is set to fall behind the rest of Asia.

Also Read: Reliance on China: Diwali in dragon’s shadow

This is not only because of global headwinds but also domestic factors. The debt-fuelled real estate boom has turned bust. Brutal zero-Covid lockdowns in important cities like Shanghai have also played a role. The growing rivalry with the US is leading to denial of semiconductor technologies and relocation of supply chains away from the mainland. Looking ahead, growth will not fire up with a rapidly-ageing population. The challenge is to kick-start consumption-led growth in an economy with the highest rates of precautionary savings. For faster growth, the need is for market-oriented reforms, which are perhaps an anathema to control-driven leaders like Xi. Although he stated to the 20th Congress that the privately-owned economy would be supported and fuller play would be given to market forces, he also added that a better play would be given to the role of the government. In the name of ensuring “common prosperity’, Xi has cracked down on tech billionaires who were not toeing the dictates of CCP. Perhaps Xi’s father was right. Xi’s ambitions to globally project China’s power can be realised by letting go of control. But isn’t that too much to ask for a leader who has ruthlessly wielded power like Mao?