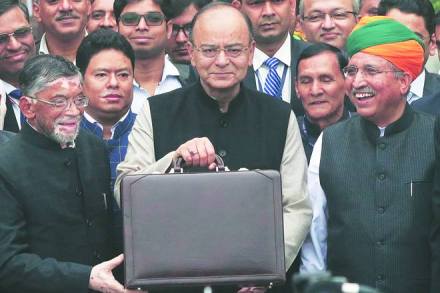

The fourth budget presented by Arun Jaitley was greeted by the usual mixture of bouquets and brickbats along predictable party lines. But among economists, the majority opinion seemed to be that it was a better than usual budget. It was, in my view, his best so far. He is getting more confident of his understanding of the complexities of the Indian economy. There is also a continuing refrain, thanks to the prime minister, of reform in each budget.

This time around, we have a new earlier date, an abolition of the distinction between plan and non-plan expenditure, a merging of the Railways Budget with the Union Budget and, as a special prize, the proposals for reform of the rules for donations to political parties.

The point still remains that each budget is a stab in the dark. Economics is unusual in having uncertainty not about the future but also about the recent and not so recent past. Figures for income levels and growth rates get revised two to three years after the event. Indeed, in India during the halcyon days of planning, we were more certain about the future than about the past.

The trouble with the budget is that, in the end, it is an accounting exercise. Accountants like their number to add up, a balance to be struck between incomings and outgoings, arriving at a deficit or surplus estimate. Jaitley struck a good balance maintaining the deficit at 3.2% though I would gave preferred 3%. But it is in these matters that the numbers get very soft. Not just in the Indian context but in the UK as well, I have proposed that budgets should be ‘fuzzy’. As of the date of Budget 2017, there were no reliable estimates of GDP, or growth rate for FY17 for the obvious reason that the fiscal year is not yet over. If the date of budget presentation is to be February 1 from now on, the finance ministry will gave to develop a procedure or at least some explanatory note on the likely income and the growth rate, plus the variation which would be probable. One way would be to take the calendar year estimates—i.e., the last quarter of the previous fiscal plus three quarters of the current fiscal which have passed by February 1—of income and its growth rate as a leading predictor of the fiscal year numbers.

Ideally, a budget should be in terms of a range of estimates of revenue and expenditure. The central forecast could be as of now the most likely outcome. Departments can plan on the basis of the central forecast. But the fuzzy lines would indicate that economic life has a lot of uncertainty both in terms of estimates and outcomes. We now have budget estimates ex ante and revised estimates ex post. But, even the revised estimates are sometime the same as the ex ante ones, as this year’s direct tax collection estimates are. The same is true for indirect tax collections. But that is to be expected if you have to get the numbers for a February 1 budget.

The government should make a virtue of this necessity and get Parliament and the public used to the idea of a fan diagram of the main components of the budget. One needs to convey to the people that it is because economics is a science unlike astrology, there cannot be 100% certainty. The fuzzy budget could give a range of , for example, the deficit projected with allowance for the outcome being different from that which is budgeted, that said, it is the Economic Survey which has launched the subject of Universal Basic Income (UBI) for discussion; it would be ambitious indeed if the government was to provide a basic Income for everyone. Of course, if only 5% of the GDP is to be spent on the UBI, then each individual recipient can only have 5% of per capita income as their share. If we take per capita income to be R100,000, then R5,000 is each person’s share. Call this a supplement rather than income.

I did some work on this topic for the UK economy in the 1990s and concluded that it is not easy, if you take Milton Friedman’s negative tax idea then the tax rate at the threshold level , say 10% of R2.5 lakh ,i.e., R25,000 is what each individual, tax payer or not, should get. It is not easy to pay that much to each individual, whether tax payer or not.

My proposal is to turn the UBI into an income supplement for women. Women work in the household—cooking, cleaning, raising children and most looking after the sick and tired. Most women do housework for no pay. It would empower them if they got a sum of say 10% of per capita income paid into their dedicated bank account; it may also discourage female infanticide if parents knew that a girl child is valuable. That would revolutionise Indian society.

The author is a prominent economist and Labour peer