By Harsh V Pant & Kalpit Mankikar

The Chinese leadership has been likened by some observers to a row of ducks moving in a pond, which sometimes barely creates a ripple despite the frenetic peddling. Now, there has been a churn in the ranks of the Chinese Communist Party (CCPP), with allegations of corruption levelled against China’s defence minister Li Shangfu and some of his erstwhile associates. This development comes in close succession to the mysterious eclipse of China’s foreign minister Qin Gang, and an anti-corruption purge in the top echelons of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Rocket Force, in charge of the nation’s nuclear arsenal.

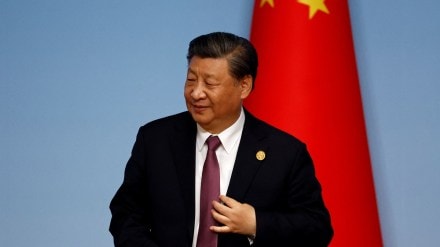

The case of the missing mandarins leaves behind some uneasy questions. First, at the 20th Party Congress, Chinese president Xi Jinping called for rapid modernisation of the PLA and has been goading his generals to train soldiers under actual combat conditions. But suddenly, the needle has moved from personnel to the quality of PLA’s armaments. Since last year, China has resorted to military drills in the Taiwan straits to browbeat the island’s government. Have these PLA manoeuvres revealed the proverbial chinks in the armour? Another possibility is that repeated “stress tests” in the form of cross-straits war games to gauge the efficacy of personnel and weaponry might have revealed some shortcomings. In that case, is there a bigger military gameplan for the near future?

Second, the Communist Party mouthpiece, People’s Daily, published a report of an inspection team that found deficiencies in the Rocket Force units in charge of conventional and nuclear missiles. This, coupled with the Central Military Commission’s (CMC) assessment calling for improvement in PLA’s weapons acquisitions and upgrading the quality of weaponry is a condemnation of Li, who served in the CMC’s Equipment Division. Now, if indeed Li’s fall is on account of shoddy defence equipment, it dents the painstaking effort in China’s domestic propaganda to spruce up Xi’s role in the transformation of the PLA as a modern force. There has been an attempt in the Chinese state media to portray that the military had been exposed to risks under previous leaderships and that Xi carried out the task of rebuilding the army and purging it of corrupt generals. The argument implies that Xi’s predecessors allowed a drift in the armed forces, endangering national security. It may be recalled that there was a purge of CMC chairpersons Xu Caihou, Guo Boxiong, and other senior military figures shortly after Xi took over on grounds that they had been responsible for pocketing payoffs in lieu of doling out promotions in the armed forces. The downfall of senior figures in the military establishment revealed the extent of the unsavoury practice of buying ranks in the services, which had put a question mark on one of the world’s largest armies.

Third, the Communist Party of China in 2022 issued probity norms relating to the business interests of officials’ kin. The objective was to limit the officials from exploiting the aegis of the CCP to further their interests through their kin. Xi had asserted that while China was at the cusp of an “overwhelming” victory in the battle against corruption, more work was required to meet the challenge. He also said that the need of the hour was to ensure that officials did not fall into the trap of corruption because they “do not dare to, are not able to and do not want to”. Doesn’t l’affaire Shangfu represent the failure of Xi’s anti-corruption campaign, since it would mean that a big fish managed to swim past graft-busters?

Fourth, evidence from recent events shows that there may be another possibility. In the run up to the 2012 Party Congress, it transpired that Gu Kailai, wife of then Politburo member Bo Xilai, had a hand in the murder of UK businessman Neil Heywood. Media reports tied Heywood to British intelligence, though the UK government denied that he was employed with the secret service. Does corruption in the PLA offer an opening for rival powers?

Lastly, what impact could these corruption cases have on Xi’s hold on power? There is considerable speculation regarding policy directions in the Xi regime. Reports recently surfaced that Xi had been reprimanded at the Beidaihe conclave—a key institutional intra-party dialogue mechanism—that is attended by CPC seniors. It may serve him well to remember the fate of Romania’s Nicolae Ceausescu, who had greatly centralised personal power but ended up being ousted by the army and his own Communist Party colleagues. The challenges of over-centralisation in a Communist setup have been evident for long. One of the reasons why the CCP has managed so far is because of its ability to learn right lessons from the failures of other Communist regimes.

Growing domestic challenges have dented Xi Jinping’s image as an efficient leader. From being the engine of the global economy, China today finds itself in a slump with declining growth, rising youth unemployment and a deepening real estate crisis. Xi’s foreign policy has created adversaries all around China’s periphery. There is a crisis of confidence in China that has put Xi’s leadership under spotlight. It’s a dangerous time for the world as there might be an attempt by Beijing to divert attention from internal issues by creating a crisis abroad.

Harsh V Pant & Kalpit Mankikar, respectively, vice president, Studies and Foreign Policy and fellow, Strategic Studies programme, ORF. Views are personal.