In the late 1990s, studies were carried out by the ministry of road transport & highways to evaluate the benefits that accrue to road users in terms of the reduction in the operating and maintenance cost of their vehicles owing to improved quality of highways and, in particular, the upgrading of national highways (NH) from two lanes to four lanes with divided carriageway. It was felt that part of the benefit could be recovered from the users in the form of user charges. In order to mitigate the impact of such charges on the users, it was decided that, where required, it must be treated a part of the capital as grant by the government and recover the rest from users.

This policy decision was to come in very useful when prime minister AB Vajpayee announced a major highway development project, the National Highways Development Project (NHDP) in 1998-99, which involved the development of 13,000 km of NH into four-lane highways at an estimated cost of R60,000 crore. To raise some part of the financial resources, the government decided to levy a R1 per litre cess on petrol and diesel for being invested in a statutory road fund.

Nevertheless, the amount which could be raised through the cess was insignificant in terms of the finances required for undertaking the NHDP, particularly when a substantial part of the cess was to be used for a major rural roads programme. It was, therefore, decided that the amount available through the road fund can be better used to leverage assistance from the multi-lateral institutions and financing by the private sector through different models of PPP. For this purpose, the collection of user charges or tolls was to help in providing an appropriate return to the private sector on their investment.

Model concession agreements were drawn up where the concerns of the different parties in the PPP were sought to be addressed. However, tolling of highways, on such a major scale, had not been attempted earlier, and apprehension was expressed about the possible impact of tolling on the likely growth of traffic and the viability of projects. Some of these concerns were to be addressed through the concession agreement, and further with some part of the private sector risk being taken over by the government by making available of a grant up to 40% of the capital cost. Even so, the apprehensions persisted and some projects were then offered where the entire risk was assumed by the government on payment of a predetermined annuity amount.

Also Watch:

After the initial hesitation, the PPP model finally took off and has been one of the major success stories of private sector involvement in the development and operation of public assets. Starting from a base of around 200/300 km in the year 2000, more than 27,000 km of national highways have been developed into four/six lane highways, with a significant contribution of the private sector. This has led to the development of a highways industry with all the attendant branches of construction, engineering and finance. The development has also been recognised by the market, with players successfully raising capital. A noteworthy development has been the entry of long-term funds in the O&M stage.

However, now, we are witnessing a perceptible easing off in the use of the PPP format in the development of national highways. During FY16, the total length of roads awarded by the government was to the tune of 10,000 km and total length of roads constructed was 6,029 km. The total length of highways awarded up to November 2016 was 5,688 km and total length of highway constructed was 4,021 km. The number of projects awarded by NHAI during FY16 was 79, of which only seven were in the BOT format, 63 on EPC mode and nine on Hybrid Annuity Model, which are, in terms of their risk profile, not very different than EPC. In the current year, of the total 41 projects awarded so far, only three were in BOT format, 17 in HAM and 21 in the EPC format. Of greater concern, would be the fact that out of the 36 PPP projects awarded in the last two years, only 10 are toll-based PPPs, reflecting in some ways a reluctance or lack of appetite for toll based projects. There has also been no progress in the award of O&M toll based contracts for sections developed by the Authority. If this perception is correct, then it would represent a major turnaround in policy which was adopted at the time of the commencement of the NHDP. Lending substance to this perception is the stoppage of tolling on some ongoing highways which have, in turn, created contractual issues.

The crucial importance of investment in infrastructure was recognised in the 12th Plan document when it said that higher investment in infrastructure is critical for the revival of the investment climate as it would lead to enhanced investment in manufacturing. Within the investment space for infrastructure, a much larger role was visualised for private sector, whose share was expected to go upto 48% from the 36.6% level achieved during the 11th Plan period. For the area of roads & bridges itself, the document envisaged more than three-fold increase in private sector investment with a level of R3.04 lakh crore against the expenditure of R0.93 lakh crore in the 11th Plan period. In this regard, the document states that the NHDP needs to be stepped up with an aggressive pursuit of PPP to construct toll roads on a BOT basis. This need has certainly not gone away with the policy requirement of bringing down the fiscal deficit. Clearly, therefore, the endeavour on PPP in roads has to be an ongoing effort.

Apart from the financing aspect, PPP has many other notable impacts. They add a significant level of implementation capacity in the system that is more efficient in its concern about time and cost. It helps to focus on the shortcomings within the system, and thus provide an earlier and more timely response to problems and impediments. In comparison, the departmental systems, in case of item rate and even EPC contracts, would tend to cover up the deficiencies in terms of land availability, utilities shifting, time and cost overruns and so on, resulting in a more sub-optimal outcome. There have been some problems, in the past, in the implementation of PPP projects, but these have helped to create a better understanding. Most important, these experiences validate that, given the uncertainties in financing costs, traffic and market risks, long-term PPP decisions are based on incomplete information with both the public and the private sectors, and therefore a decision taken a decade ago, based on the then prevailing market scenario, should not be deemed to be mala fide, rigged or one sided. Nevertheless, a strong contracting and dispute redressal mechanism with options for renegotiating the concession could be put in place for improving the risk profile for PPP projects and encourage investors to come forward.

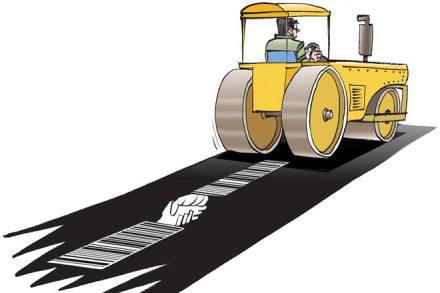

Within the PPP space, the policy goal of augmenting available funding with private resources is best achieved in the user pay model, whether for the development of the highways through BOT (tolls) or their maintenance through toll based O&M contracts. Long-term funds deployed for these contracts would be the ideal way of financing the NH programme. For this to happen the adherence to policy and sanctity or the inviolability of contracts are indispensable ingredients. The underlying significance of tolling in the overall policy has, therefore, to be stressed and the misconception regarding toll being imposed only to recover capital correctly clarified. At the same time, the genuine difficulties of users, particularly local commuters, need to be addressed with greater facilities for tag users, etc. Overall road conditions have to conform to contract conditions and the sense of value for money being registered in the minds of users. In the context of overall development in the sector, it is time perhaps for a road regulator to be established. Judicial & executive intervention in user-pay principles should be kept only where security of the nation or of a similar serious genre is anticipated by its levy.

In an environment where vehicle users are having to submit themselves to pollution and congestion charges, surely a small amount paid as user charges for the development and maintenance of our highways cannot be considered too irksome. After all, as the former US President, John F Kennedy, reportedly remarked, “it’s not wealth that built our roads but the roads that built the wealth”.

The author, Deepak Dasgupta, is former chairman, NHAI