By N Chandra Mohan

India’s efforts to repair ties with China—that have been in deep freeze after a deadly border clash five years ago—are part of its larger diplomatic drive to rearrange its great power relations. Although India’s foreign policy has been increasingly aligned with that of the West, especially the US, it also has strategic relationships with major powers like Russia in a multipolar world. This delicate balancing act is now under pressure due to the upending of a rules-based international order by US President Donald Trump. The world is fragmenting along geopolitical lines, broadly into US-and Sino-centric blocs. At a time when its relations with Washington are under severe stress, New Delhi hopes to reset its relations with Beijing.

Border thaw but fragile peace

To be sure, India has limited geopolitical options in this regard. The rapprochement with China is constrained by serious concerns about the security of its northern flank, with 50,000 well-armed troops amassed on both sides of the border. The US is exerting pressure on India to stop purchasing Russian oil, which risks antagonising its time-tested and reliable relations with Moscow. But what happens to these historical ties if there is a deal with the US that enables Russia to return to the international mainstream? A grand bargain between Washington and Beijing also cannot be ruled out. As India is no more a swing state, it must salvage its strategic partnership with the US while also normalising ties with China.

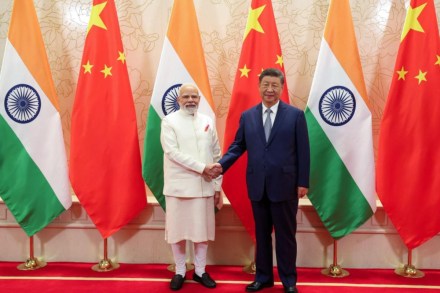

The US, China, Russia, and India constitute “four moving parts of a quadrilateral geopolitical system”, according to former diplomat Pankaj Saran. Bilateral interactions between each affect their relations with the other, while each bilateral relationship is impacted by developments in the other relationships, he added. With all these bilateral relationships in flux due to the disruption in the global order, India must fashion independent relationships with all the major powers. Not surprisingly, when Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi recently met Chinese President Xi Jinping in Tianjin, he noted that both countries pursue strategic autonomy and their relations should not be seen through a third-country lens.

Economic gap and strategic limits

What then are the prospects of the elephant dancing with the dragon? At Tianjin, there was more than a handshake between Modi and Xi as a semblance of peace and tranquillity has returned to the border. This had a lot to do with the processes set in motion when they met at a BRICS summit in Kazan last October. They tasked their special representatives to oversee border management. As a result, India’s National Security Advisor Ajit Doval and his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi held two rounds of discussions during the last nine months. Wang also met India’s external affairs minister and the PM. Modi noted the progress on this front that after disengagement, “an atmosphere of peace and stability is now in place”.

But the border situation remains fragile despite welcome signs of disengagement of troops on friction points in eastern Ladakh. The process of de-escalation and de-induction is still some distance away. India has to remain on high alert as China has rapidly built up infrastructure along the entire line of actual control; as a result, its troops can pull back 100-150 km and then return swiftly in two-three hours, which cannot be done by our forces. The border question is an important point of difference between India and China. While New Delhi considers quiet borders and restoring conditions to how they were before 2020 as a precondition for normalisation, Beijing feels this dispute should not define the overall bilateral relationship.

Unfortunately, there are no easy solutions to the fraught border situation. Over the long haul, it can only be resolved by narrowing the economic power differential between India and China. Although India is the world’s fifth largest economy, China is six times larger as the second largest economy. This is reflected in relative military strength, with India in a disadvantageous position to resolve the issue through force. Look no further than the huge military parade in Beijing on Wednesday—to celebrate the 80th anniversary of victory over Japan—that will showcase the latest hypersonic and strategic missiles, tanks, and uncrewed weapons. India must steadily build up its economy through rapid growth to narrow this differential.

How then can ties be normal when China recognises India only as a weaker neighbour? India has not succeeded in imposing severe economic costs on the dragon for its border transgressions. China continues to find a way around existing restrictions in investing in India. BBK Electronics and Haier made investments of $230 million and $120 million in January and March, according to American Enterprise Institute’s China global investment tracker. With a trade deficit of $99.2 billion, India’s dependence on the dragon appears more akin to a third world country that exports raw materials while importing manufactured goods from the mainland. China has used coercive economic measures to block shipments of rare earths, fertilisers, and tunnel boring equipment; it has also withdrawn its technicians involved in iPhone assembly in the country. Negotiating a mutually advantageous deal—rather than a one-sided one—is highly challenging despite signs of a Himalayan thaw.

The writer is an economics and business commentator based in New Delhi.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal and do not reflect the official position or policy of FinancialExpress.com. Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited.