Raman Lamba died three times. Once on a cricket field in Dhaka when a ball hit his head. Once in a hospital when his brain gave up. And once in our memory, because we only talk about the first two. That’s the real tragedy. Not the accident.

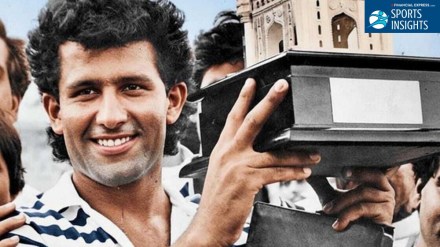

Most people remember Raman Lamba for how he died but that is a disservice to the man who lived with such loud, colourful energy. He was the original “fitness freak” in Indian cricket long before gym sessions became a trend. He played the game like a gladiator, with his collar up and his chest out. He was a man of huge runs, big smiles and a spirit that couldn’t be contained by borders.

Sonnet Club: Middle-class boys with rich-man dreams

Tarak Sinha ran a cricket club in Delhi called Sonnet. He didn’t care about fancy batting grips or perfect cover drives. He wanted boys who were angry about being poor. Boys who thought cricket was their only way to buy a house for their parents.

Raman Lamba was one of them.

The Sonnet ground was dust and hope. No turf wickets. No AC rooms. Just boys from places like Karol Bagh and Patel Nagar who practiced with second-hand kits.

Raman stood out not because he was talented. Half the boys were talented. He stood out because he was crazy.

While others took water breaks, he ran laps. While others complained about the heat, he asked for throwdowns. His coach would say, “This one has fire,” and he did. He burned through every excuse Indian cricket had for being unfit in the 1980s.

Running while everyone else slept

In 1985, Indian cricketers thought fitness meant not eating a second gulab jamun. Raman thought it meant running ten kilometers before practice. He would be at Ferozshah Kotla at 5:30 AM, alone, doing drills he read about in foreign magazines.

People laughed. “Why are you tiring yourself? Ranji matches are five days. You need stamina, not muscles.”

But Raman knew something they didn’t. He knew bowlers get tired before batsmen do. He knew that after six hours, a fit batsman sees a different ball. A slower ball. A looser ball. A ball you can hit for four. That’s exactly what he did. For twenty years, he made domestic bowlers cry. Not with talent. With pure, boring fitness.

King of triple hundreds

The 1987 Duleep Trophy final. West Zone versus North Zone. Raman batted for twelve hours straight. That’s not a typo. Twelve hours. He made 320 runs. Hit the ball to the fence thirty times. Cleared it six times. The West Zone bowlers stopped appealing. They just wanted to go home. Raman wouldn’t let them. He stayed. And stayed. And stayed.

This wasn’t his only triple century. He did it again; 312 against Himachal Pradesh. While other batsmen celebrated hundreds, Raman celebrated hours spent. His average stayed above 53 in domestic cricket for two decades. That’s not luck. That’s a man who treated bowling attacks like personal treadmills.

Summer of 1986: When Australia Learned His Name

The 1986 Australia tour. Six one-day matches. Raman made 278 runs. Player of the Series. But numbers don’t tell you how he made them. He charged fast bowlers. Not occasionally. Every over.

He would walk down the pitch to Aussie bowlers and hit him over covers like he was playing school cricket. Alongside K Srikkanth, he turned opening batting into a street fight. The world saw this style again in the 1996 World Cup. Raman had already done it ten years earlier.

His Test career didn’t last. Only four matches. But that summer, every Australian bowler knew one thing: this Delhi boy doesn’t respect reputation. He only respects his own Swing of the bat.

Ireland’s fourth choice hero

In 1984, North Down club in Northern Ireland needed a professional. They had three other names before Raman. He was a backup plan. By the end of the season, they wanted to build him a statue.

Raman didn’t drink beer. Didn’t smoke cigarettes. In a club where professionals usually partied hard, he coached kids. Hit massive sixes. Then coached more kids. The locals loved him because he wasn’t a star. He was one of them. Just better at cricket.

Kim worked at the club. She wasn’t impressed by cricketers. But Raman was different. He stayed. They married. Had two kids. Bought a house. The Irish cricket board changed their rules because Raman was too good. They limited how many runs a professional could score.

Think about that. A Delhi boy was so good, they had to write new rules.

For Raman, Ireland wasn’t a job. It was the only place where people let him be normal.

Three Balls: Dhaka, 23 February 1998

Bangladesh called him the Don of Dhaka. He had been playing there for years, making runs, winning hearts. February 23, 1998. Abahani versus Mohammedan. Big match. Raman was fielding at forward short leg. The dangerous spot. The helmet-eater spot.

There were only three balls left in the over. He was asked to wear a helmet, but he refused, thinking he didn’t need it for such a short time.

The next ball, Mehrab Hossain hit a massive pull shot. The ball struck Lamba on the head with a terrible sound. He actually walked off the field himself, but his brain was bleeding. He told a teammate, “Bulli, main to mar gaya” (I am dead, Bulli). He fell into a coma and died three days later at just 38 years old.

Cap on the coffin

After the accident, cricket boards made helmets mandatory for close-in fielders. They talked about safety. But the real moment was his funeral.

Kim, his wife, placed his old Sonnet Club cap on his head. The same cap he wore as a hungry boy in Delhi. The same cap he carried to Ireland. The same cap he forgot in Dhaka because he thought three balls couldn’t kill a gladiator.

That’s the real story. Not the rule change. The cap. The circle. The boy from dust who became a hero in three countries and died because he thought he was invincible.

Raman Lamba lived like every ball was his last. That’s why he made so many runs. That’s why people loved him. That’s why we should remember him; not as a safety warning, but as a man who made cricket look like the most fun you could have with a piece of wood and leather.